| Issue |

A&A

Volume 499, Number 1, May III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 191 - 213 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811511 | |

| Published online | 25 March 2009 | |

Radio emission and nonlinear diffusive shock acceleration of cosmic rays in the supernova SN 1993J

V. Tatischeff

1 - Centre de Spectrométrie Nucléaire et de Spectrométrie de

Masse, CNRS/IN2P3 and Univ Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay, France![]()

2 - Institut de Ciències de l'Espai (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB,

Fac. Ciències, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain

Received 12 December 2008 / Accepted 13 March 2009

Abstract

Aims. The extensive observations of the supernova SN 1993J at radio wavelengths make this object a unique target for the study of particle acceleration in a supernova shock.

Methods. To describe the radio synchrotron emission we use a model that couples a semianalytic description of nonlinear diffusive shock acceleration with self-similar solutions for the hydrodynamics of the supernova expansion. The synchrotron emission, which is assumed to be produced by relativistic electrons propagating in the postshock plasma, is worked out from radiative transfer calculations that include the process of synchrotron self-absorption. The model is applied to explain the morphology of the radio emission deduced from high-resolution VLBI imaging observations and the measured time evolution of the total flux density at six frequencies.

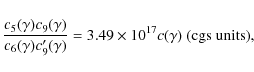

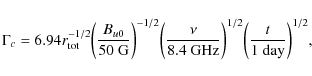

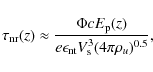

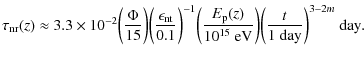

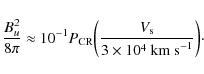

Results. Both the light curves and the morphology of the radio emission indicate that the magnetic field was strongly amplified in the blast wave region shortly after the explosion, possibly via the nonresonant regime of the cosmic-ray streaming instability operating in the shock precursor. The amplified magnetic field immediately upstream from the subshock is determined to be

![]() G. The turbulent magnetic field was not damped behind the shock but carried along by the plasma flow in the downstream region. Cosmic-ray protons were efficiently produced by diffusive shock acceleration at the blast wave. We find that during the first

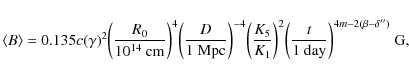

G. The turbulent magnetic field was not damped behind the shock but carried along by the plasma flow in the downstream region. Cosmic-ray protons were efficiently produced by diffusive shock acceleration at the blast wave. We find that during the first ![]() 8.5 years after the explosion, about 19% of the total energy processed by the forward shock was converted to cosmic-ray energy. However, the shock remained weakly modified by the cosmic-ray pressure. The high magnetic field amplification implies that protons were rapidly accelerated to energies well above 1015 eV. The results obtained for this supernova support the scenario that massive stars exploding into their former stellar wind are a major source of Galactic cosmic-rays of energies above

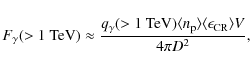

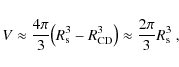

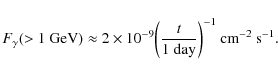

8.5 years after the explosion, about 19% of the total energy processed by the forward shock was converted to cosmic-ray energy. However, the shock remained weakly modified by the cosmic-ray pressure. The high magnetic field amplification implies that protons were rapidly accelerated to energies well above 1015 eV. The results obtained for this supernova support the scenario that massive stars exploding into their former stellar wind are a major source of Galactic cosmic-rays of energies above ![]() 1015 eV. We also calculate the flux from SN 1993J of gamma-rays arising from collisions of accelerated cosmic rays with ambient material and the result suggests that type II supernovae could be detected in

1015 eV. We also calculate the flux from SN 1993J of gamma-rays arising from collisions of accelerated cosmic rays with ambient material and the result suggests that type II supernovae could be detected in ![]() -decay gamma-rays with the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope out to a maximum distance of only

-decay gamma-rays with the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope out to a maximum distance of only ![]() 1 Mpc.

1 Mpc.

Key words: acceleration of particles - magnetic fields - radiation mechanisms: non-thermal - stars: supernovae: individual: SN 1993J

1 Introduction

Galactic cosmic rays are widely believed to be accelerated in expanding shock waves initiated by supernova (SN) explosions, at least up to the ``knee'' energy of the cosmic-ray spectrum at ![]() 1015 eV and possibly up to the ``ankle'' at

1015 eV and possibly up to the ``ankle'' at ![]() 1018 eV (Axford 1994). The theory of diffusive shock acceleration (DSA) of cosmic rays is well established (see, e.g., Jones & Ellison 1991; Malkov & Drury 2001, for reviews), but two fundamental questions remain partly unanswered by the theory: what is the maximum kinetic energy achieved by particles accelerated in SN shocks and what is the acceleration efficiency, i.e. the fraction of the total SN energy converted to cosmic-ray energy?

1018 eV (Axford 1994). The theory of diffusive shock acceleration (DSA) of cosmic rays is well established (see, e.g., Jones & Ellison 1991; Malkov & Drury 2001, for reviews), but two fundamental questions remain partly unanswered by the theory: what is the maximum kinetic energy achieved by particles accelerated in SN shocks and what is the acceleration efficiency, i.e. the fraction of the total SN energy converted to cosmic-ray energy?

The maximum cosmic-ray energy attainable in a SN shock scales as the product of the shock size and the strength of the turbulent magnetic field in the acceleration region (e.g. Marcowith et al. 2006). Multiwavelength observations of young shell-type supernova remnants (SNRs) provide evidence that the magnetic field in the blast wave region is much higher than the interstellar magnetic field (e.g. Völk et al. 2005; Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2007; Uchiyama et al. 2007, and references therein). A possible explanation for these observations is that the ambient magnetic field is amplified by the diffusive streaming of accelerated particles in the upstream region of the shock, which could cause a plasma instability generating large-amplitude magnetic turbulence

(Bell & Lucek 2001; Amato & Blasi 2006; Vladimirov et al. 2006). Magnetic field amplification via this nonlinear process could facilitate the acceleration of protons in SNRs up to ![]() 1015 eV (e.g. Parizot et al. 2006).

1015 eV (e.g. Parizot et al. 2006).

The acceleration efficiency depends on the diffusive transport of energetic particles at both sides of the shock in the self-generated turbulence (e.g. Malkov & Drury 2001). The DSA theory cannot accurately predict at the present time how many particles are injected into the acceleration process as a function of the shock parameters. Observations of SNRs in high-energy gamma-rays can provide valuable information on the efficiency of cosmic-ray acceleration in these objects. But it remains unclear whether the emission detected from several SNRs with ground-based atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes is due mainly to pion decay following hadronic collisions of accelerated ions or to inverse Compton scattering of ambient photons by accelerated electrons (e.g. Morlino et al. 2008).

However, theory predicts that efficient acceleration of cosmic-ray ions (mainly protons) modifies the shock structure with respect to the case with no acceleration (see, e.g., Berezhko & Ellison 1999). In particular, the total compression ratio of a cosmic-ray-modified shock can be much higher than that of a test-particle shock (i.e. when the accelerated particles have no influence on the shock structure), because relativistic particles produce less pressure for a given energy density than do nonrelativistic particles. In addition, the energy loss due to escape of accelerated cosmic rays from the shock system can further increase the compressibility of the shocked gas (see Decourchelle et al. 2000). Furthermore, since the energy going into relativistic particles is drawn from the shocked-heated thermal population, the postshock temperature of a cosmic-ray-modified shock can be much lower than the test-particle value. Observations of these nonlinear effects (Hughes et al. 2000; Decourchelle 2005; Warren et al. 2005) provide indirect evidence for the efficient acceleration of cosmic-ray protons (which carry most of the total nonthermal particle pressure) in shock waves of young SNRs.

In this paper, we study the production of cosmic-rays by nonlinear DSA and the associated magnetic field amplification in a very young SN shock, which expands in a relatively dense stellar wind lost by the progenitor star prior to explosion. We use radio monitoring observations of SN 1993J conducted with the Very Large Array and several other radio telescopes since the SN outburst (see Weiler et al. 2007; Bartel et al. 2007, and references therein). The radio emission from SNe is thought to be synchrotron radiation from relativistic electrons of energies <1 GeV accelerated at the expanding blast wave (Chevalier 1982b; Fransson & Björnsson 1998). The key motivation for the present study is that the radiating electrons can be influenced by the presence of otherwise unseen shock-accelerated protons. In particular, the theory of nonlinear DSA predicts that the energy distribution of nonthermal electrons below 1 GeV steepens with increasing efficiency of proton acceleration (Ellison et al. 2000).

We chose SN 1993J because it is one of the brightest radio SNe ever detected and has already been the subject of numerous very useful observational and theoretical studies (see, e.g., for the radio emission of SN 1993J Bartel et al. 1994,2000,2007; Marcaide et al. 1994,1995,1997; Van Dyk et al. 1994; Fransson et al. 1996; Fransson & Björnsson 1998; Pérez-Torres et al. 2001; Mioduszewski et al. 2001; Bietenholz et al. 2003; Weiler et al. 2007, and references therein).

The model of the present paper is largely based on the work of Cassam-Chenaï et al. (2005; see also Decourchelle et al. 2000; Ellison & Cassam-Chenaï 2005) on the morphology of synchrotron emission in Galactic SNRs. These authors have developed a model to study radio and X-ray images of SNRs undergoing efficient cosmic-ray production, that couples a semianalytic description of nonlinear DSA with self-similar solutions for the hydrodynamics of the SN expansion. The model has recently been applied to the remnants of Tycho's SN (Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2007) and SN 1006 (Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2008).

Duffy et al. (1995) have studied the radio emission from SN 1987A by considering a two-fluid system consisting of a cosmic-ray gas and a thermal plasma to calculate the structure of the blast wave. In their model, however, the efficiency of cosmic-ray acceleration is not deduced from the radio data, but assumed to be similar to that required in SNRs to explain the observed flux of Galactic cosmic rays. Another difference with the present work is that the turbulent magnetic field in the shock precursor is not assumed to be amplified by the DSA process, but is taken by these authors to be of the same order as the ordered field in the wind of the progenitor star.

A preliminary account of the present work has been given elsewhere (Tatischeff 2008) and all of the present results supersede those published earlier.

2 Model

2.1 Forward shock expansion

The type IIb SN 1993J was discovered in the galaxy M 81 by Garcia (Ripero

et al. 1993) on 1993 March 28, shortly after shock breakout (Wheeler

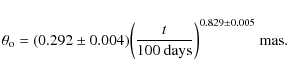

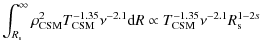

et al. 1993). Very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) observations (see, e.g., Marcaide et al. 1997; Bietenholz et al. 2003) revealed a decelerating expansion of a shell-like radio source. The radio emission is presumably produced between the forward shock propagating into the circumstellar medium (CSM) and the reverse shock running into the SN ejecta (e.g. Bartel et al. 2007). Marcaide et al. (1997) found the outer angular radius of the radio shell to evolve as a function of time t after explosion with the power law

![]() ,

where the deceleration parameter

,

where the deceleration parameter

![]() .

More recently, Weiler et al. (2007, and references therein) reported that the angular expansion of SN 1993J up to day 1500 after outburst can be expressed as

.

More recently, Weiler et al. (2007, and references therein) reported that the angular expansion of SN 1993J up to day 1500 after outburst can be expressed as

![]()

![]() as with

as with

![]() ;

here

;

here ![]() is by definition the angular radius of the circle that encompasses half of the total radio flux density to better than 20%.

is by definition the angular radius of the circle that encompasses half of the total radio flux density to better than 20%.

These results are consistent with the standard, analytical model for the expansion of a SN into a CSM (Chevalier 1982a,1983; Nadyozhin 1985). This model assumes power-law density profiles for both the outer SN ejecta,

![]() (with n>5), and the CSM,

(with n>5), and the CSM,

![]() (with s<3), where C2 and C1 are constants. The SN expansion is then found to be self-similar (i.e. the structure of the interaction region between the forward and reverse shocks remains constant in time except for a scaling factor) and the deceleration parameter

m=(n-3)/(n-s). For a standard wind density profile with s=2 (see below), the deceleration reported by Weiler et al. (2007) corresponds to

(with s<3), where C2 and C1 are constants. The SN expansion is then found to be self-similar (i.e. the structure of the interaction region between the forward and reverse shocks remains constant in time except for a scaling factor) and the deceleration parameter

m=(n-3)/(n-s). For a standard wind density profile with s=2 (see below), the deceleration reported by Weiler et al. (2007) corresponds to

![]() ,

in fair agreement with numerical computations of SN explosions (e.g. Arnett 1988).

,

in fair agreement with numerical computations of SN explosions (e.g. Arnett 1988).

However, Bartel et al. (2000,2002) found significant changes with time of the parameter m, indicating deviations from a self-similar expansion. These authors determined the outer angular radius

![]() as a function of time by consistently fitting to the two-dimensional radio images observed at 34 epochs between 1993 and 2001 the projection of a three-dimensional spherical shell of uniform volume emissivity. They fixed the ratio of the outer to inner angular radius (as expected from a self-similar expansion) at

as a function of time by consistently fitting to the two-dimensional radio images observed at 34 epochs between 1993 and 2001 the projection of a three-dimensional spherical shell of uniform volume emissivity. They fixed the ratio of the outer to inner angular radius (as expected from a self-similar expansion) at

![]() .

By performing a least-squares power-law fit to the values of

.

By performing a least-squares power-law fit to the values of

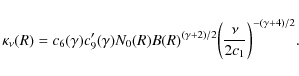

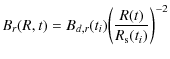

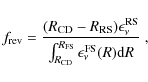

![]() thus determined (see Fig. 1), they obtained a minimum reduced

thus determined (see Fig. 1), they obtained a minimum reduced ![]() of

of

![]() for 64 degrees of freedom, indicating that the null hypothesis of a self-similar expansion can be rejected.

for 64 degrees of freedom, indicating that the null hypothesis of a self-similar expansion can be rejected.

As discussed by Bartel et al. (2002), this result strongly depends on the systematic errors associated with the model of uniform emissivity in the spherical shell. The overall systematic uncertainty was estimated to range from 3% at early epochs to 1% at later epochs and to dominate the statistical error in most of the cases. We show below (Sect. 3.1) that the assumption of uniform emissivity is questionable, because radio-emitting electrons accelerated at the forward shock are expected to lose most of their kinetic energy by radiative losses before reaching the contact discontinuity between shocked ejecta and shocked CSM (see also Fransson & Björnsson 1998). Furthermore, the radial emissivity profile is expected to vary with time and radio frequency![]() . Although the systematic uncertainties were carefully studied by Bartel et al. (2002), we note that a moderate increase of the errors would make the expansion compatible with the self-similar assumption. For example, by setting a lower limit of 3% on the uncertainties in the outer radii measured by Bartel et al., we get from a least-squares power-law fit to the data

. Although the systematic uncertainties were carefully studied by Bartel et al. (2002), we note that a moderate increase of the errors would make the expansion compatible with the self-similar assumption. For example, by setting a lower limit of 3% on the uncertainties in the outer radii measured by Bartel et al., we get from a least-squares power-law fit to the data

![]() and an associated probability of chance coincidence of 8%. Thus, the null hypothesis of a self-similar expansion could not anymore be rejected at the usual significance level of 5%.

and an associated probability of chance coincidence of 8%. Thus, the null hypothesis of a self-similar expansion could not anymore be rejected at the usual significance level of 5%.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg68.png) |

Figure 1: Time evolution of the outer angular radius of the shell-like radio emission from SN 1993J. The data were obtained by Bartel et al. (2002) from observations at 1.7, 2.3, 5.0, 8.4, 14.8, and 22.2 GHz. The dotted line is a least-squares power-law fit to the data (Eq. (1)). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

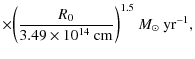

For simplicity, I shall use the self-similar solution to model the hydrodynamic evolution of the SNR (Sect. 2.5). The radius of the forward shock,

![]() where the source distance

where the source distance

![]() Mpc (Freedman et al. 1994), is estimated from a power-law fit to the data of Bartel et al. (2002) at all frequencies (Fig. 1), which gives

Mpc (Freedman et al. 1994), is estimated from a power-law fit to the data of Bartel et al. (2002) at all frequencies (Fig. 1), which gives

Thus, we have

In the self-similar model, the forward shock radius is given by (e.g. Chevalier 1983)

where the constant

where

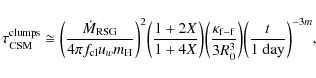

2.2 Free-free absorption of the radio emission in the circumstellar medium

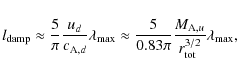

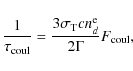

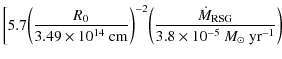

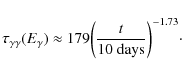

Figure 2 shows a set of light curves measured for SN 1993J at 0.3 cm (85-110 GHz), 1.2 cm (22.5 GHz), 2 cm (14.9 GHz), 3.6 cm (8.4 GHz), 6 cm (4.9 GHz), and 20 cm (1.4 GHz). We see that at each wavelength the flux density first rapidly increases and then declines more slowly as a power in time (the data at 0.3 cm do not allow to clearly identify this behavior). The radio emission was observed to suddenly decline after day ![]() 3100 (not shown in Fig. 2), which is interpreted in terms of an abrupt decrease of the CSM density at radial distance from the progenitor

3100 (not shown in Fig. 2), which is interpreted in terms of an abrupt decrease of the CSM density at radial distance from the progenitor

![]() cm (Weiler et al. 2007). This is presumably the outer limit of the dense cocoon which was established by a high mass loss from the red supergiant progenitor of the SN for

cm (Weiler et al. 2007). This is presumably the outer limit of the dense cocoon which was established by a high mass loss from the red supergiant progenitor of the SN for ![]() 104 years before explosion.

104 years before explosion.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{1511f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg85.png) |

Figure 2: Radio light curves for SN 1993J at 0.3, 1.2, 2, 3.6, 6, and 20 cm. The data are from Weiler et al. (2007) and references therein. The solid lines represent the best-fit semi-empirical model of these authors. The dotted lines show a synchrotron self-absorption (SSA) model in which the SSA optical depth and the unabsorbed flux density were obtained from fits to radio spectra taken between day 75 and day 923 after outburst (see Sect. 2.3). The difference between the latter model and the data before day 100 is partly due to free-free absorption of the radio emission in the CSM. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We see in Fig. 2 that the maximum intensity is reached first at lower wavelengths and later at higher wavelengths, which is characteristic of absorption processes. For SN 1993J, both free-free absorption (FFA) in the CSM and synchrotron self-absorption (SSA) are important (Chevalier 1998; Fransson & Björnsson 1998; Weiler et al. 2007). The Razin effect can be excluded (Fransson & Björnsson 1998). FFA is produced in the stellar wind that has been heated and ionized by radiation from the shock breakout. If the circumstellar gas is homogeneous and of uniform temperature

![]() ,

the radio emission produced behind the forward shock is typically attenuated by a factor

,

the radio emission produced behind the forward shock is typically attenuated by a factor

![]() ,

where the optical depth at a given frequency

,

where the optical depth at a given frequency ![]() satisfies (Weiler et al. 1986)

satisfies (Weiler et al. 1986)

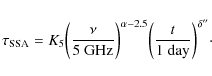

From a fit to early data using the parametrized model of Weiler et al. (1986,2002; see Appendix A), Van Dyk et al. (1994) found for the time dependance of the optical depth

Fransson & Björnsson (1998) performed the most detailed modeling of the radio emission from SN 1993J to date. In particular, they took into account both FFA and SSA, and included all relevant energy loss mechanisms for the relativistic electrons. As a result, they were able to adequately reproduce the radio light curves with the standard s=2 density profile. In their model, the measured time dependence of the FFA optical depth (i.e. ![]() )

is accounted for by a decrease of

)

is accounted for by a decrease of

![]() with radius like

with radius like

![]() (see also Fransson

et al. 1996). However, as pointed out by Weiler et al. (2002), no evidence for such a radial dependence of

(see also Fransson

et al. 1996). However, as pointed out by Weiler et al. (2002), no evidence for such a radial dependence of

![]() is found in other radio SNe (e.g. SN 1979C and SN 1980K).

is found in other radio SNe (e.g. SN 1979C and SN 1980K).

Immler et al. (2001) provided support from X-ray observations to the scenario of a flatter CSM density profile, as they found s=1.63 from modeling of the observed X-ray light curve. Their analysis assumes that the X-ray emission arises from the forward, circumstellar shock. But later than ![]() 200 days post-outburst, the X-ray radiation was more likely produced in the SN ejecta heated by the reverse shock (Fransson & Björnsson 2005, and references therein).

200 days post-outburst, the X-ray radiation was more likely produced in the SN ejecta heated by the reverse shock (Fransson & Björnsson 2005, and references therein).

With the model of the present paper, the measured radio light curves can be well explained with the standard s=2 assumption, but not with a much flatter CSM density profile. This result is independent of the admittedly uncertain FFA modeling, as we will see in Sect. 4.1 that with s=1.6 the optically thin emission cannot be simultaneously reproduced at all wavelengths in the framework of the model (see Fig. 14). So the question is how a

![]() density profile can be reconciled with the relatively low value of

density profile can be reconciled with the relatively low value of ![]() implied by the data.

implied by the data.

A possible explanation is that the absorbing CSM is inhomogeneous. Both radio (Weiler et al. 1990) and optical and UV (e.g. Tran et al. 1997) observations show that the wind material lost from SN progenitors can be clumpy and/or filamentary. FFA of the radio emission by a nonuniform CSM can be accounted for by an attenuation factor of the form

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the maximum of the optical depth distribution, which depends on the number density and geometric cross section of the clumps of wind material (Natta & Panagia 1984; Weiler et al. 2002). Weiler et al. (2007) performed an overall fit to all of the measured radio light curves of SN 1993J using a parametrized model that takes into account both SSA and FFA, and includes both attenuation by a homogeneous and inhomogeneous CSM (see Appendix A). In their best-fit model (solid lines in Fig. 2), FFA is mainly due to the clumpy CSM, the corresponding optical depth,

is the maximum of the optical depth distribution, which depends on the number density and geometric cross section of the clumps of wind material (Natta & Panagia 1984; Weiler et al. 2002). Weiler et al. (2007) performed an overall fit to all of the measured radio light curves of SN 1993J using a parametrized model that takes into account both SSA and FFA, and includes both attenuation by a homogeneous and inhomogeneous CSM (see Appendix A). In their best-fit model (solid lines in Fig. 2), FFA is mainly due to the clumpy CSM, the corresponding optical depth,

![]() ,

being much larger than

,

being much larger than

![]() in the optically thick phase for all wavelengths (see Table 4 in Weiler et al. 2007).

in the optically thick phase for all wavelengths (see Table 4 in Weiler et al. 2007).

In view of these results, we are going to neglect in first approximation the attenuation of the radio emission by the homogeneous component of the CSM in front of the attenuation by the clumpy CSM, which will allow us to derive in a simple way and self-consistently the mass loss rate of the progenitor star and the structure of the radio emission region (see below). We anticipate, however, that the adopted simple FFA model will not allow us to accurately reproduce the rising branches of the light curves in the optically thick phase.

Following Weiler et al. (1986,2002), the optical depth produced by FFA in a clumpy presupernova wind can be written as

with, for a uniform

Here,

where we adopted X=0.3 (e.g. Shigeyama et al. 1994). In the following we use uw=10 km s-1 and

FFA in the progenitor wind of SN 1993J is estimated below from the following iterative process. First the synchrotron emission as a function of time after outburst is calculated from a set of reasonable initial parameters. External FFA is then estimated from an overall fit of the calculated light curves to the radio data, using Eqs. (A.3) and (A.6) for the CSM attenuation factor with fixed

![]() (see Eq. (6)). Thus, the only free parameter is K3. The corresponding progenitor mass loss rate is obtained from Eq. (8). The derived wind density just upstream from the forward shock,

(see Eq. (6)). Thus, the only free parameter is K3. The corresponding progenitor mass loss rate is obtained from Eq. (8). The derived wind density just upstream from the forward shock,

![]() ,

is then used to calculate the shock properties and the associated synchrotron emission. The process is continued until convergence is reached.

,

is then used to calculate the shock properties and the associated synchrotron emission. The process is continued until convergence is reached.

2.3 Time evolution of the mean magnetic field in the synchrotron-emitting region

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=13cm]{1511f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg116.png) |

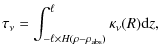

Figure 3:

Evolution of the parameters

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the original model of Chevalier (1982b) for the radio emission from SNe, the magnetic energy density in the radio-emitting shell is assumed to scale as the total postshock energy density (

![]() ), such that the strength of the mean magnetic field

), such that the strength of the mean magnetic field

![]() for s=2. Later on, Chevalier (1996,1998) also considered that the postshock magnetic field could result from the compression of the circumstellar magnetic field, which would imply

for s=2. Later on, Chevalier (1996,1998) also considered that the postshock magnetic field could result from the compression of the circumstellar magnetic field, which would imply

![]() .

Because SSA plays an important role in the radio emission from SN 1993J, the evolution of the magnetic field can be estimated from the measured light curves. Fransson & Björnsson (1998) found, however, the two scaling laws

.

Because SSA plays an important role in the radio emission from SN 1993J, the evolution of the magnetic field can be estimated from the measured light curves. Fransson & Björnsson (1998) found, however, the two scaling laws

![]() and

and

![]() to be compatible with the data for SN 1993J available at that time.

to be compatible with the data for SN 1993J available at that time.

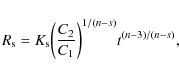

We re-estimate here the temporal evolution of

![]() using the fitting model of Weiler et al. (1986,2002) together with the simple formalism given in Appendix A. We analyze individual radio spectra at various dates of observation to determine the time variation of the fitted parameters. The method is similar to the one previously employed by Fransson & Björnsson (1998).

using the fitting model of Weiler et al. (1986,2002) together with the simple formalism given in Appendix A. We analyze individual radio spectra at various dates of observation to determine the time variation of the fitted parameters. The method is similar to the one previously employed by Fransson & Björnsson (1998).

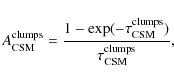

We use observations made with the Very Large Array (VLA) in which a non-zero flux density was measured at at least five wavelengths at the same time (1.2, 2, 3.6, 6, and 20 cm). The corresponding data were obtained later than 75 days after explosion (see Fig. 2). We also use the data at 90 cm taken at day 922.7 post-outburst. Each radio spectrum is fitted with the function

![]() ,

where the attenuation factors are given by Eqs. (A.3) and (A.4), with the corresponding optical depths

,

where the attenuation factors are given by Eqs. (A.3) and (A.4), with the corresponding optical depths

![]() and

and

![]() .

The fitting function thus contains four free parameters:

.

The fitting function thus contains four free parameters:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

.

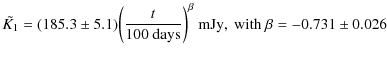

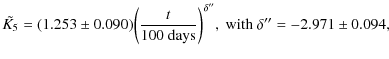

The best-fit parameters are shown in Fig. 3. We took into account only the spectral fits of relatively good quality, with

![]() .

It was checked that the final result is not strongly dependent on this data selection. The FFA optical depth

.

It was checked that the final result is not strongly dependent on this data selection. The FFA optical depth

![]() was found to be compatible with zero at most epochs. No regular evolution of this parameter can be deduced from the fitting results (Fig. 3c). On the other hand, the temporal evolutions of

was found to be compatible with zero at most epochs. No regular evolution of this parameter can be deduced from the fitting results (Fig. 3c). On the other hand, the temporal evolutions of

![]() and

and

![]() can be well described by power-law fits

(Figs. 3a and 3d). We found

can be well described by power-law fits

(Figs. 3a and 3d). We found

with reduced

We have neglected here the correlations between the various fitted parameters in the error determination, which is a good approximation given that the error in the magnetic field at day 100 mainly arises from the uncertainty in the source distance (9.4%) and the error in the power-law index b is dominated by the uncertainty in

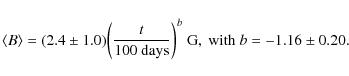

The mean magnetic field given by Eq. (10) is in good agreement with the one obtained by Fransson & Björnsson (1998). But in contrast with the conclusions of these authors, the value of b obtained in the present analysis indicates that the scaling law

![]() can be excluded at the 90% confidence level. The discrepancy is partly due to the different assumptions made for the SN expansion. Indeed, Fransson & Björnsson (1998) assumed m=1 for t<100 days (i.e.

can be excluded at the 90% confidence level. The discrepancy is partly due to the different assumptions made for the SN expansion. Indeed, Fransson & Björnsson (1998) assumed m=1 for t<100 days (i.e.

![]() )

and m=0.74 at later epochs. The FFA model is also different in the two analyses. However, because the present result is restricted to relatively late epochs, it is only weakly dependent of the FFA modeling.

)

and m=0.74 at later epochs. The FFA model is also different in the two analyses. However, because the present result is restricted to relatively late epochs, it is only weakly dependent of the FFA modeling.

A ``pure'' SSA model calculated with

![]() and the best-fit power laws for

and the best-fit power laws for

![]() and

and

![]() (Eq. (9)) is shown in Fig. 2. We see that this model does not correctly represent the data taken before day 100. This is partly because free-free attenuation of the radio emission in the CSM was not taken into account. But it is also due to the strong radiative losses suffered by the radio-emitting electrons at early epochs (see Fransson & Björnsson 1998, and Sect. 3 below), which are not included in the parametric formalism of Weiler et al. (2002, and references therein) used here. As we will see below, one of the main effects of the electron energy losses is to reduce the flux density at short wavelengths during the transition from the optically thick to the optically thin regime. If this effect is not properly taken into account, the relative contributions of FFA and SSA at early epochs post-outburst cannot be reliably estimated. Consequently, the magnetic field determination for these epochs is uncertain. We assume here that the time evolution of

(Eq. (9)) is shown in Fig. 2. We see that this model does not correctly represent the data taken before day 100. This is partly because free-free attenuation of the radio emission in the CSM was not taken into account. But it is also due to the strong radiative losses suffered by the radio-emitting electrons at early epochs (see Fransson & Björnsson 1998, and Sect. 3 below), which are not included in the parametric formalism of Weiler et al. (2002, and references therein) used here. As we will see below, one of the main effects of the electron energy losses is to reduce the flux density at short wavelengths during the transition from the optically thick to the optically thin regime. If this effect is not properly taken into account, the relative contributions of FFA and SSA at early epochs post-outburst cannot be reliably estimated. Consequently, the magnetic field determination for these epochs is uncertain. We assume here that the time evolution of

![]() determined from day 75 after explosion was the same at earlier times.

determined from day 75 after explosion was the same at earlier times.

We also see in Fig. 2 that the decline with time of the optically-thin emission calculated in the SSA model is too slow as compared to the data at 20 cm. A possible explanation is that the energy distribution of the radiating electrons deviates from a power law of constant spectral index, as implicitly assumed in the above modeling (but see below).

The derived time dependence of

![]() is consistent with the scaling law originally adopted by Chevalier (1982b),

is consistent with the scaling law originally adopted by Chevalier (1982b),

![]() .

In Chevalier's model, the scaling law is based on the assumption that the postshock magnetic field is built up by a turbulent amplification powered by the total available postshock energy density. We will see in Sect. 4.3 that the temporal evolution

.

In Chevalier's model, the scaling law is based on the assumption that the postshock magnetic field is built up by a turbulent amplification powered by the total available postshock energy density. We will see in Sect. 4.3 that the temporal evolution

![]() is also to be expected if the magnetic field is amplified by Bell (2004)'s nonresonant cosmic-ray streaming instability in the shock precursor region and if furthermore the shock is not strongly modified by the back pressure from the energetic ions. We note that the time dependence

is also to be expected if the magnetic field is amplified by Bell (2004)'s nonresonant cosmic-ray streaming instability in the shock precursor region and if furthermore the shock is not strongly modified by the back pressure from the energetic ions. We note that the time dependence

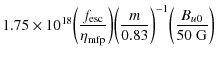

![]() was also recently reported by Soderberg et al. (2008) for the type Ibc SN 2008D. Therefore, based on both observational evidences and a theoretical basis, I assume in the following that the postshock magnetic field results from an amplification by the cosmic-ray streaming instability operating in the shock precursor and that the field immediately upstream from the subshock is of the form

was also recently reported by Soderberg et al. (2008) for the type Ibc SN 2008D. Therefore, based on both observational evidences and a theoretical basis, I assume in the following that the postshock magnetic field results from an amplification by the cosmic-ray streaming instability operating in the shock precursor and that the field immediately upstream from the subshock is of the form

![]() ,

where Bu0 is a free parameter to be determined from fits to the radio data.

,

where Bu0 is a free parameter to be determined from fits to the radio data.

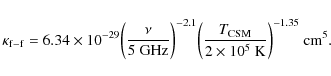

2.4 Nonlinear particle acceleration

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm]{1511f4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg137.png) |

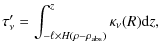

Figure 4:

Shocked proton and electron phase-space distributions vs. kinetic energy, at day 1000 after shock breakout. Following Berezhko & Ellison (1999), the phase-space distribution functions have been multiplied by

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

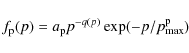

Particle acceleration at the forward shock is calculated with the semianalytic model of nonlinear DSA developed by Berezhko & Ellison (1999) and Ellison

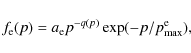

et al. (2000). Although the model strictly applies to plane-parallel, steady state shocks, it has been successfully used by Ellison et al. (2000) for evolving SNRs and more recently by Tatischeff & Hernanz (2007) to describe the evolution of the blast wave generated in the 2006 outburst of the recurrent nova RS Ophiuchi. The main feature of this relatively simple model is to approximate the nonthermal part of the shocked proton and electron phase-space distributions as a three-component power law with an exponential cutoff at high momenta,

and

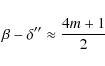

where the power-law index q(p), which is the same for protons and electrons, can have three different decreasing values in the momentum ranges

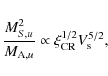

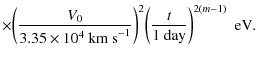

The maximum proton momentum

![]() is calculated either by time integration of the DSA rate (i.e., shock age limitation) or by equalling the upstream diffusion length to some fraction

is calculated either by time integration of the DSA rate (i.e., shock age limitation) or by equalling the upstream diffusion length to some fraction

![]() of the shock radius (i.e., particle escape limitation), whichever produces the lowest value of

of the shock radius (i.e., particle escape limitation), whichever produces the lowest value of

![]() (see, e.g., Baring et al. 1999). Following, e.g., Ellison & Cassam-Chenaï (2005), I take

(see, e.g., Baring et al. 1999). Following, e.g., Ellison & Cassam-Chenaï (2005), I take

![]() .

To estimate the spatial diffusion coefficient,

.

To estimate the spatial diffusion coefficient,

![]() ,

the scattering mean free path

,

the scattering mean free path ![]() of all particles of speed v is assumed to be

of all particles of speed v is assumed to be

![]() (Ellison et al. 2000), where

(Ellison et al. 2000), where ![]() is the particle gyroradius and

is the particle gyroradius and

![]() is a constant that characterizes the scattering strength. I use

is a constant that characterizes the scattering strength. I use

![]() ,

which is a typical value for young SNRs (Parizot et al. 2006). The maximum electron momentum

,

which is a typical value for young SNRs (Parizot et al. 2006). The maximum electron momentum

![]() is limited by synchrotron and inverse Compton losses (see Sect. 2.6).

is limited by synchrotron and inverse Compton losses (see Sect. 2.6).

Given the upstream sonic and Alfvén Mach numbers of the shock, which can be readily calculated from ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and Bu0 (see below), the proton distribution function (i.e. the normalization

,

and Bu0 (see below), the proton distribution function (i.e. the normalization ![]() and power-law

index q(p)) is determined by an arbitrary injection parameter

and power-law

index q(p)) is determined by an arbitrary injection parameter

![]() ,

which is the fraction of total shocked protons in protons with momentum

,

which is the fraction of total shocked protons in protons with momentum

![]() injected from the postshock thermal pool into the DSA process. The work of Blasi et al. (2005) allows us to accurately relate the proton injection momentum

injected from the postshock thermal pool into the DSA process. The work of Blasi et al. (2005) allows us to accurately relate the proton injection momentum

![]() to

to

![]() .

.

The normalization of the electron distribution function is obtained from (Ellison et al. 2000)

where

where

Alfvén wave heating of the shock precursor is taken into account from the simple formalism given in Berezhko & Ellison (1999). However, a small change to the model of these authors is adopted here: the Alfvén waves are assumed to propagate isotropically in the precursor region and not only in the direction opposite to the plasma flow, i.e. Eqs. (52) and (53) of Berezhko & Ellison (1999) are not used. This is a reasonable assumption (see, e.g., Bell & Lucek 2001) given the strong, nonlinear magnetic field amplification required to explain the radio emission from SN 1993J.

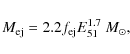

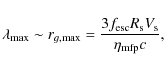

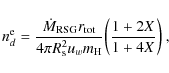

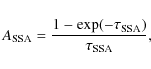

Figure 4 shows calculated shocked proton and electron phase-space distributions for three sets of injection parameters (

![]() ,

,

![]() )

that will be used in Sect. 3.2 to model the radio light curves. The thermal Maxwell-Boltzmann components were calculated using the shocked proton temperature

)

that will be used in Sect. 3.2 to model the radio light curves. The thermal Maxwell-Boltzmann components were calculated using the shocked proton temperature

![]() determined by the nonlinear DSA model (see, e.g., Ellison et al. 2000) and arbitrarily assuming the temperature ratio

determined by the nonlinear DSA model (see, e.g., Ellison et al. 2000) and arbitrarily assuming the temperature ratio

![]() .

Noteworthy, the nonthermal electron distribution is independent of

.

Noteworthy, the nonthermal electron distribution is independent of

![]() when

when

![]() is specified (see Eq. (13)) except for the electron injection momentum

is specified (see Eq. (13)) except for the electron injection momentum

The uncertain temperature ratio has thus practically no influence on the modeled radio emission.

We see in Fig. 4a that for

![]() the well-known test-particle result q(p)=4 is recovered. But for

the well-known test-particle result q(p)=4 is recovered. But for

![]() (Figs. 4b and c) the nonlinear shock modification becomes significant. In particular we see that the nonthermal electron distribution steepens below

(Figs. 4b and c) the nonlinear shock modification becomes significant. In particular we see that the nonthermal electron distribution steepens below ![]() GeV with increasing

GeV with increasing

![]() ,

as a result of the decrease of

,

as a result of the decrease of

![]() (Eq. (14)). This is important because the radio emission from SN 1993J is produced by relativistic electrons of energies <1 GeV.

(Eq. (14)). This is important because the radio emission from SN 1993J is produced by relativistic electrons of energies <1 GeV.

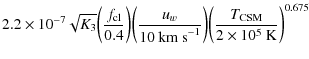

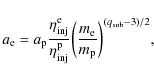

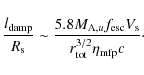

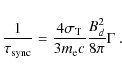

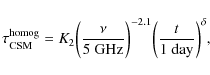

Figure 5 shows calculated subshock and total compression ratios for the case

![]() which, as will be shown in Sect. 3.2, provides the best description of the radio light curves. The calculations were performed with the upstream sonic Mach number

which, as will be shown in Sect. 3.2, provides the best description of the radio light curves. The calculations were performed with the upstream sonic Mach number

![]() ,

given the upstream sound velocity

,

given the upstream sound velocity

![]() km s-1 for

km s-1 for

![]() K. Here

K. Here

![]() is the adiabatic index for an ideal non-relativistic gas, k is the Boltzmann's constant, and

is the adiabatic index for an ideal non-relativistic gas, k is the Boltzmann's constant, and

![]() .

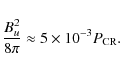

Given the magnetic field immediately upstream from the subshock

.

Given the magnetic field immediately upstream from the subshock

![]() ,

the Alfvén Mach number

,

the Alfvén Mach number

![]() is independent of time; here

is independent of time; here

![]() is the Alfvén velocity. Anticipating the results presented in Sect. 3, with the best-fit parameter values Bu0=50 G and

is the Alfvén velocity. Anticipating the results presented in Sect. 3, with the best-fit parameter values Bu0=50 G and

![]() yr-1, we have

yr-1, we have

![]() .

Thus,

.

Thus,

![]() ,

which implies that energy should be very efficiently transfered from the accelerated particles to the thermal gas via Alfvén wave dissipation in the shock precursor region (Berezhko & Ellison 1999). The resulting increase in the gas pressure ahead of the viscous subshock limits the overall compression ratio,

,

which implies that energy should be very efficiently transfered from the accelerated particles to the thermal gas via Alfvén wave dissipation in the shock precursor region (Berezhko & Ellison 1999). The resulting increase in the gas pressure ahead of the viscous subshock limits the overall compression ratio,

![]() ,

to values close to 4 (i.e. the standard value for a test-particle strong shock).

,

to values close to 4 (i.e. the standard value for a test-particle strong shock).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg181.png) |

Figure 5:

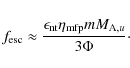

Subshock and total compression ratios at the forward shock ( left axis) and nonthermal energy fraction

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

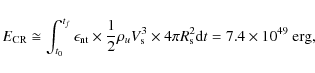

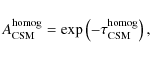

However, we see in Fig. 5 that the acceleration efficiency

![]() increases with time. This quantity is defined as the fraction of total incoming energy flux,

increases with time. This quantity is defined as the fraction of total incoming energy flux,

![]() ,

going into shock-accelerated nonthermal particles. At day 3100 after outburst, when the shock has reached the outer boundary of the dense progenitor wind,

,

going into shock-accelerated nonthermal particles. At day 3100 after outburst, when the shock has reached the outer boundary of the dense progenitor wind,

![]() %. The subshock compression ratio is found to slowly decrease with time, as the shock becomes increasingly modified. Thus, we expect a gradual steepening with time of the electron distribution between

%. The subshock compression ratio is found to slowly decrease with time, as the shock becomes increasingly modified. Thus, we expect a gradual steepening with time of the electron distribution between

![]() and

and

![]() (Eq. (14)).

(Eq. (14)).

Given the high turbulent magnetic field in the shock region, the timescale for diffusive acceleration of electrons in this momentum range is very rapid,

![]() h. This is much shorter than the characteristic timescale for variation of the shock structure (see Fig. 5), so it is justified to assume that the spectrum of the radio-emitting electrons at a given time is determined by the instantaneous subshock compression ratio at that time. We note, however, that

our calculation of the high-energy end of the proton spectrum is not accurate, because the acceleration timescale for the highest energy particles is much longer.

h. This is much shorter than the characteristic timescale for variation of the shock structure (see Fig. 5), so it is justified to assume that the spectrum of the radio-emitting electrons at a given time is determined by the instantaneous subshock compression ratio at that time. We note, however, that

our calculation of the high-energy end of the proton spectrum is not accurate, because the acceleration timescale for the highest energy particles is much longer.

2.5 Magnetohydrodynamic evolution of the postshock plasma

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg187.png) |

Figure 6:

Radial profiles of a) the gas density and b) the total magnetic field in the shock region. The density is normalized to the upstream value

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The hydrodynamic evolution of the postshock plasma is calculated using the self-similar model (Chevalier 1982a,1983; Nadyozhin 1985) with the deceleration parameter m=0.83 (Sect. 2.1), the standard s=2 density profile (Sect. 2.2), and the adiabatic index

![]() .

Thus, the effects of the back pressure from the accelerated ions on the dynamics of the SNR are neglected. It is a good approximation for SN 1993J given that

.

Thus, the effects of the back pressure from the accelerated ions on the dynamics of the SNR are neglected. It is a good approximation for SN 1993J given that

![]() for the best parameter value

for the best parameter value

![]() (Fig. 5). The situation is different in older SNRs, such as the remnant of Kepler's (Decourchelle et al. 2000) and Tycho's (Warren et al. 2005) SNe. In these objects, the backreaction of shock-accelerated cosmic rays has more influence on the shock structure, mainly because the magnetic field in the precursor region is much lower than for SN 1993J, such that Alfvén wave heating is less important.

(Fig. 5). The situation is different in older SNRs, such as the remnant of Kepler's (Decourchelle et al. 2000) and Tycho's (Warren et al. 2005) SNe. In these objects, the backreaction of shock-accelerated cosmic rays has more influence on the shock structure, mainly because the magnetic field in the precursor region is much lower than for SN 1993J, such that Alfvén wave heating is less important.

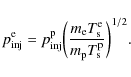

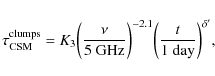

Figure 6a shows the density profile in the region of interaction between the SN ejecta and the progenitor wind. The locations of the forward and reverse shocks are clearly visible, at 1.27 and 0.976 times the radius of the contact discontinuity, respectively.

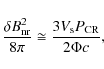

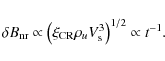

The postshock magnetic field is thought to result from the shock compression of the turbulent magnetic field immediately upstream from the subshock, that has been presumably amplified in the precursor region by both resonant (Bell & Lucek 2001) and nonresonant (Bell 2004) cosmic-ray streaming instabilities. Following the work of Cassam-Chenaï et al. (2007) for Tycho's SNR, I make two different assumptions about the postshock magnetic field evolution: one where the turbulent magnetic field is simply carried by the downstream plasma flow (i.e. advected) and another where the magnetic turbulence is rapidly damped behind the blast wave.

2.5.1 Advected downstream magnetic field

The equations describing the evolution of the postshock magnetic field in the case of pure advection in the downstream plasma are given in Cassam-Chenaï

et al. (2005) and references therein. They are reproduced here for sake of convenience. Let the radial and tangential components of the immediate postshock magnetic field be Bd,r and Bd,t, respectively. Assuming that the upstream magnetic field is fully turbulent and isotropic, we have

At time t after outburst, the radial and tangential components of the magnetic field in a fluid element with density

where ti is the earlier time when this fluid element was shocked and

The radial profile of the total advected magnetic field is shown in Fig. 6b. Under the assumption of self-similarity, the plotted ratio B(R)/Bd is independent of time.

2.5.2 Damped downstream magnetic field

Pohl et al. (2005) suggested that the nonthermal X-ray filaments observed in Galactic SNRs could be localized enhancements of the magnetic field in the blast wave region. In this scenario, the turbulent magnetic field amplified in the shock presursor is thought to be rapidly damped behind the shock front by cascading of wave energy to very small scales where it is ultimately dissipated.

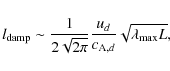

Assuming a Kolmogorov-type energy cascade of incompressible magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) turbulence, the characteristic damping length can be estimated to be (Pohl

et al. 2005; see also Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2007)

where

such that

For

We see that for

Pohl et al. (2005) also considered that downstream magnetic field damping can result from cascading of fast-mode and Alvén waves in background

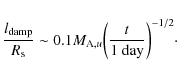

MHD turbulence. In these cases, we have (see also Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2007)

where L is the outer scale of the pre-existing MHD turbulence. Assuming that this quantity is of the order of the diameter of the dense wind bubble blown by the red supergiant progenitor of the SN,

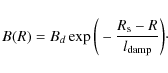

This damping length is thus always larger (for t<3100 days) than the one estimated from the general model of Kolmogorov-type energy cascade (Eq. (24)). In the case of damping by cascading of fast-mode and Alfvén waves the spatial relaxation of the postshock magnetic field follows an exponential decay law

Postshock magnetic field profiles obtained from Eqs. (26) and (27) with

2.6 Nonthermal electron energy losses

The cooling processes that can affect the energy distribution of the nonthermal electrons during the SN expansion were studied by Fransson & Björnsson (1998). They found synchrotron cooling to be predominant for electrons radiating at short wavelengths for most of the time, Coulomb cooling to be potentially important at early epochs post-outburst, adiabatic cooling to be dominant for electrons radiating at 20 cm at late epochs and inverse Compton losses due to electron scattering off photons from the SN photosphere to be less important. These results depend, however, on several model parameters, e.g. the progenitor mass loss rate

![]() and the magnetic field Bu0.

and the magnetic field Bu0.

With the best parameter values of the present model, Coulomb cooling is found to be more important than synchrotron cooling only at very early epochs, when the radio emission is still optically thick to SSA (Sect. 4.2). At that time, the energy losses of the shock-accelerated electrons have little if no effect on the radio emission, such that Coulomb cooling can be safely neglected. This contrasts with the model of Fransson & Björnsson (1998).

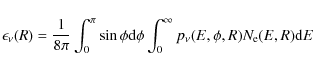

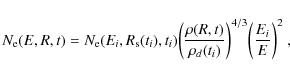

I use the work of Reynolds (1998; see also Cassam-Chenaï et al. 2007, Appendix B) to calculate the downstream evolution of the electron energy distribution due to synchrotron, inverse Compton, and adiabatic losses. The number density of nonthermal electrons per unit energy interval at kinetic energy E in a fluid element being at the downstream position R at time t can be written as

where

Here,

where

is the energy density in the radiation field,

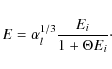

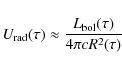

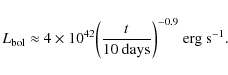

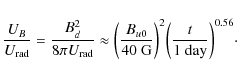

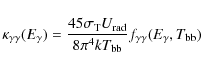

Fransson & Björnsson (1998) showed that during the first ![]() 100 days after outburst, the radiation energy density at the forward shock position was dominated by emission from the SN ejecta. They approximated the bolometric luminosity of SN 1993J at these early epochs by

100 days after outburst, the radiation energy density at the forward shock position was dominated by emission from the SN ejecta. They approximated the bolometric luminosity of SN 1993J at these early epochs by

The ratio of the energy densities of magnetic to seed photon fields in the immediate postshock region is then

This result shows that Compton cooling can play a role soon after outburst depending on the magnetic field strength, but that synchrotron cooling is expected to become more important after some time. A similar result was found by Chevalier & Fransson (2006) for type Ib/c SNe.

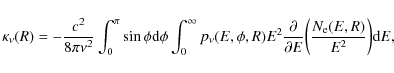

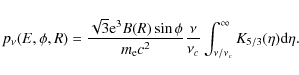

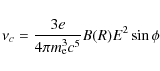

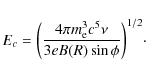

2.7 Radio synchrotron emission

Once the electron energy distribution and the magnetic field as a function of downstream position are determined as explained above, the synchrotron brightness profile and the total flux density at a given time can be calculated as described in Appendix B.

3 Results

For a given assumption about the evolution of the postshock magnetic turbulence (advection or damping), the model has four main parameters to be fitted to the radio data: the mass loss rate of the red supergiant progenitor,

![]() ,

the normalization of the upstream magnetic field, Bu0, and the proton and electron injection parameters,

,

the normalization of the upstream magnetic field, Bu0, and the proton and electron injection parameters,

![]() and

and

![]() .

In addition, the radius of the absorbing disk,

.

In addition, the radius of the absorbing disk,

![]() ,

that accounts for FFA of the radio emission by the inner SN ejecta (see Appendix B) mainly influences the brightness profile as a function of angular radius. We first compare calculated synchrotron profiles with the high-resolution profile at 3.6 cm measured by Bietenholz et al. (2003) from VLBI observations. We then study the radio light curves reported by Weiler et al. (2007).

,

that accounts for FFA of the radio emission by the inner SN ejecta (see Appendix B) mainly influences the brightness profile as a function of angular radius. We first compare calculated synchrotron profiles with the high-resolution profile at 3.6 cm measured by Bietenholz et al. (2003) from VLBI observations. We then study the radio light curves reported by Weiler et al. (2007).

3.1 The radial brightness profile

To study the radial brightness profile of SN 1993J with the highest angular resolution, Bietenholz et al. (2003) produced a composite image at 8.4 GHz from VLBI observations performed at t=2080, 2525, and 2787 days after explosion. The data were appropriately scaled to take into account the SN expansion and then averaged. The resulting brightness profile versus angular radius is shown in Fig. 7 together with two calculated profiles. Here and in the following, we set the radius of the inner opaque disk accounting for FFA of the radio emission from the side of the shell moving away from us (Appendix B) to

![]() .

We see in Fig. 7 that this simple model of absorption by the SN ejecta is consistent with the data for

.

We see in Fig. 7 that this simple model of absorption by the SN ejecta is consistent with the data for

![]() ,

but underestimates the observed emission for

,

but underestimates the observed emission for

![]() .

The difference might arise from incomplete absorption of the radio waves in the inner ejecta, possibly because the latter are filamentary (see Bietenholz et al. 2003). However, the excess of emission at

.

The difference might arise from incomplete absorption of the radio waves in the inner ejecta, possibly because the latter are filamentary (see Bietenholz et al. 2003). However, the excess of emission at

![]() accounts for only

accounts for only ![]() 3% of the total flux density and it has been neglected so as to limit the number of free parameters.

3% of the total flux density and it has been neglected so as to limit the number of free parameters.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg226.png) |

Figure 7:

Relative brightness of the 3.6 cm emission from SN 1993J at day 2787 after outburst, as a function of angular radius. In the calculations, the outer angular radius |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg228.png) |

Figure 8:

Calculated radial profiles of the relative emissivity at 3.6 cm and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

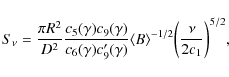

The radial brightness profile is mainly sensitive to the strength and profile of the magnetic field behind the blast wave![]() . The two calculated profiles shown in Fig. 7 are for Bu0=50 G and the case of pure advection of the field in the downstream plasma. We see in Fig. 7b that the model with only electrons accelerated at the forward shock (red dashed curve) produces a peak at

. The two calculated profiles shown in Fig. 7 are for Bu0=50 G and the case of pure advection of the field in the downstream plasma. We see in Fig. 7b that the model with only electrons accelerated at the forward shock (red dashed curve) produces a peak at

![]() that is both slightly shifted and too narrow as compared to the observed one. There is clearly a deficit of emission at

that is both slightly shifted and too narrow as compared to the observed one. There is clearly a deficit of emission at

![]() ,

i.e. from a region close to the contact discontinuity that marks the border between shocked ejecta and shocked CSM (see Fig. 6).

,

i.e. from a region close to the contact discontinuity that marks the border between shocked ejecta and shocked CSM (see Fig. 6).

As shown in Fig. 8, the radial emissivity of electrons accelerated at the blast wave is cut off before it reaches the contact discontinuity. This is due to the strong radiative losses suffered by the electrons that have been accelerated at the earliest epochs. The cutoff exists whatever the magnetic fied strength Bu0; it is mainly produced by Compton cooling for

![]() G (see Eq. (33)). Thus, the missing component of synchrotron emission is probably coming from another source of accelerated electrons, most likely the reverse shock. The efficiency of particle acceleration at reverse shocks in SNRs is poorly known, because it depends on the unknown amplification of the magnetic field in the unshocked ejecta material (Ellison et al. 2005). However, recent observations of SNRs provide clear evidence for synchrotron emission associated with reverse shocks (see Helder & Vink 2008 for Cassiopeia A). Here, we simply model this emission by a shell of uniform emissivity between the reverse shock and the contact discontinuity (Fig. 8), whose normalization is fitted to the radial brightness profile measured by Bietenholz et al. (2003). We use as normalization factor the integral of the radial emissivity relative to that for the forward shock:

G (see Eq. (33)). Thus, the missing component of synchrotron emission is probably coming from another source of accelerated electrons, most likely the reverse shock. The efficiency of particle acceleration at reverse shocks in SNRs is poorly known, because it depends on the unknown amplification of the magnetic field in the unshocked ejecta material (Ellison et al. 2005). However, recent observations of SNRs provide clear evidence for synchrotron emission associated with reverse shocks (see Helder & Vink 2008 for Cassiopeia A). Here, we simply model this emission by a shell of uniform emissivity between the reverse shock and the contact discontinuity (Fig. 8), whose normalization is fitted to the radial brightness profile measured by Bietenholz et al. (2003). We use as normalization factor the integral of the radial emissivity relative to that for the forward shock:

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg236.png) |

Figure 9:

Same as Fig. 7 but for Bu0=30 G,

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 8 also shows that the radial emissivity profile decreases more rapidly behind the blast wave as Bu0 increases, which is due to the synchrotron energy losses. Brightness profiles calculated for Bu0=30 and 80 G are compared to the data in Fig. 9. We adjusted the value of

![]() so as to match the maximum of the relative brightness to the observed one at

so as to match the maximum of the relative brightness to the observed one at

![]() .

But we see that the width of the broad emission peak is not well fitted: the calculated emission profile is too narrow (resp. too broad) for the low (resp. high) value of Bu0. Thus, the high-resolution brightness profile of Bietenholz et al. provides a first indication of the magnetic field strength in the blast wave region: 11<Bu<29 mG at day 2787 post-outburst (

30<Bu0<80 G).

.

But we see that the width of the broad emission peak is not well fitted: the calculated emission profile is too narrow (resp. too broad) for the low (resp. high) value of Bu0. Thus, the high-resolution brightness profile of Bietenholz et al. provides a first indication of the magnetic field strength in the blast wave region: 11<Bu<29 mG at day 2787 post-outburst (

30<Bu0<80 G).

The measured profile also constraints the evolution of the postshock magnetic field. Figure 10 shows that, when the magnetic field is damped behind the blast wave, the brightness angular distribution is shifted toward the outer edge of the radio shell and the resulting profile is clearly not consistent with the data. This conclusion is independent of both the value of Bu and the reverse shock contribution. In particular, the brightness profile becomes clearly too broad when

![]() is increased so as to set the maximum of the emission at

is increased so as to set the maximum of the emission at

![]() .

.

The contact interface between the SN ejecta and the shocked CSM is thought to be Rayleigh-Taylor unstable and it has been suggested that the associated turbulence can amplify the postshock magnetic field (Chevalier et al. 1992; Jun & Norman 1996). This would increase the synchrotron losses near the contact discontinuity. Consequently, the position of the cutoff in the radial emissivity would likely be shifted to larger radii with respect to the case with no amplification of the postshock magnetic field (Fig. 8). As a result, a larger contribution of synchrotron radiation from electrons accelerated at the reverse shock would probably be needed to reproduce the measured brightness profile.

However, the shocked CSM is expected to be strongly magnetized due to the field amplification by the cosmic-ray streaming instability operating in the forward shock precursor and the postshock magnetic field profile is expected to be dominated by the tangential component (see Eqs. (18) and (19)). Such a strong magnetic field could decrease the growth of the Rayleigh-Taylor instability and limit a possible additional amplification of the field by the turbulence associated with this instability (Jun et al. 1995). This aspect of the magnetohydrodynamic evolution of the postshock plasma certainly deserves further studies. Here, we assume that the postshock magnetic field is not significantly amplified by the Rayleigh-Taylor instability.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{1511f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg239.png) |

Figure 10:

Same as Fig. 7 but for the damping of the magnetic turbulence downstream ( green dashed lines) compared to the advection of the shocked plasma ( blue solid lines). In both cases, Bu0=50 G and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=13cm]{1511f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg240.png) |

Figure 11:

Radio light curves for SN 1993J at 0.3, 1.2, 2, 3.6, 6, and 20 cm. The data are from Weiler et al. (2007) and references therein. The blue solid lines represent the best-fit model, which is obtained for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Radio light curves

In the modeling of the radio light curves, we take into account the emission from electrons accelerated at the reverse shock assuming

![]() % at all times. As discussed above, this emission is then estimated to contribute to a maximum

of 17% of the total flux density. This number is an upper limit, because the synchrotron radiation from the inner shock is strongly attenuated when the emission associated with the forward shock is optically thick to SSA. We also assume

% at all times. As discussed above, this emission is then estimated to contribute to a maximum

of 17% of the total flux density. This number is an upper limit, because the synchrotron radiation from the inner shock is strongly attenuated when the emission associated with the forward shock is optically thick to SSA. We also assume

![]() at all epochs. The resulting uncertainty on the flux density is negligible.

at all epochs. The resulting uncertainty on the flux density is negligible.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{1511f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg241.png) |

Figure 12:

Radio light curves of SN 1993J with the flux density multiplied by

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{1511f13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/19/aa11511-08/Timg242.png) |

Figure 13:

Same as Fig. 12 but for various values of the injection parameters:

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

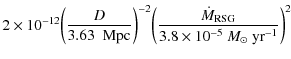

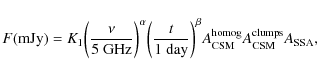

Light curves calculated with the best-fit model are shown in Fig. 11. They were obtained for

![]() yr-1, Bu0=50 G,

yr-1, Bu0=50 G,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and pure advection of the postshock magnetic field. We see that the general features of the data are fairly well represented. But the associated reduced

,

and pure advection of the postshock magnetic field. We see that the general features of the data are fairly well represented. But the associated reduced ![]() is

is

![]() (

(

![]() for 554 degrees of freedom), which is comparable to the one of the best-fit semi-empirical model of Weiler et al. (2007):

for 554 degrees of freedom), which is comparable to the one of the best-fit semi-empirical model of Weiler et al. (2007):

![]()

![]() . However, in the comparison of the

. However, in the comparison of the ![]() values, one could note that the formalism of Weiler et al. has nine free parameters (Appendix A), against only four in the present model. Interestingly, the present model is also good at representing the 12 data points at 0.3 cm (

values, one could note that the formalism of Weiler et al. has nine free parameters (Appendix A), against only four in the present model. Interestingly, the present model is also good at representing the 12 data points at 0.3 cm (

![]() ), which is not the case for the parametric model of Weiler

et al. (

), which is not the case for the parametric model of Weiler

et al. (

![]() ;

see Fig. 2). The 0.3 cm flux density between

;

see Fig. 2). The 0.3 cm flux density between ![]() 10 and

10 and ![]() 40 days after outburst is lower in the present calculations than in previous ones, because the strong synchrotron losses suffered by the radiating electrons during the early SN expansion are now taken into account. The difference is more pronounced at the shortest wavelength, because this emission is produced by higher-energy electrons (on average), for which the synchrotron cooling time is lower (

40 days after outburst is lower in the present calculations than in previous ones, because the strong synchrotron losses suffered by the radiating electrons during the early SN expansion are now taken into account. The difference is more pronounced at the shortest wavelength, because this emission is produced by higher-energy electrons (on average), for which the synchrotron cooling time is lower (

![]() ,

,

![]() being the electron Lorentz factor; see Sect. 4.2). Obviously, this effect cannot be accounted for by models neglecting the electron energy losses and assuming a homogeneous shell of emission (Chevalier 1982b,1998;

Pérez-Torres et al. 2001; Weiler et al. 2002; Soderberg et al. 2005).

being the electron Lorentz factor; see Sect. 4.2). Obviously, this effect cannot be accounted for by models neglecting the electron energy losses and assuming a homogeneous shell of emission (Chevalier 1982b,1998;

Pérez-Torres et al. 2001; Weiler et al. 2002; Soderberg et al. 2005).

However, significant deviations of the best-fit model from the data can be observed in Fig. 11. In particular, we see that the straight rising branches of the calculated light curves do not represent well the observations at 2 and 3.6 cm. This is most likely due to our treatment of external FFA (Sect. 2.2). It is possible that the structure of the CSM was more complicated at the time of explosion than that implicitly assumed by adopting an attenuation of the form

![]() with

with

![]() .

This would be the case if, for example, the filling factor of clumpy material was not constant throughout the whole CSM. It is also possible that the CSM temperature

.

This would be the case if, for example, the filling factor of clumpy material was not constant throughout the whole CSM. It is also possible that the CSM temperature

![]() was not uniform but varied with radius. However, we note that the data at 6 and 20 cm are very well fitted. The best-fit normalization to the FFA optical depth is

was not uniform but varied with radius. However, we note that the data at 6 and 20 cm are very well fitted. The best-fit normalization to the FFA optical depth is

![]() ,

which gives from Eq. (8)

,

which gives from Eq. (8)

![]() yr-1.

yr-1.

Like for the brightness profile, the light curves provide clear evidence that the postshock magnetic field is essentially advected behind the shock. Indeed, we see in Fig. 11 that the synchrotron flux declines much too rapidly after about day 100 in the model with damping of magnetic turbulence.

The modeling of external FFA being uncertain, we now focus on the optically thin parts of the radio emission. In Figs. 12 and 13, the flux density is multiplied by a time-dependent power law to set upright the decreasing parts of the light curves and the vertical scale is expanded. Figure 12 shows the effect of changing the magnetic field strength. For each value of Bu0, the electron injection rate was adjusted to provide a decent fit to the data at 3.6 cm. We see that only the model with Bu0=50 G represents the data at all the other wavelengths reasonably well. For example, for

Bu0=100 G the calculated flux densities at 0.3 cm fall short of the data, whereas those at 20 cm are too high in the optically thin phase. This effect is due to the process of synchrotron cooling, whose rate increases with the magnetic field (

![]() )

and which steepens the energy distribution of the accelerated electrons during their advection downstream. Thus, the mean propagated spectrum of nonthermal electrons is too steep (resp. too hard) for

Bu0=100 G (resp. Bu0=20 G) to provide a good fit to the data at all frequencies. It is remarkable that when the synchrotron losses are taken into account, the degeneracy for the optically-thin emission between the magnetic field and the nonthermal electron density (e.g. Chevalier 1998) is lifted.

)

and which steepens the energy distribution of the accelerated electrons during their advection downstream. Thus, the mean propagated spectrum of nonthermal electrons is too steep (resp. too hard) for

Bu0=100 G (resp. Bu0=20 G) to provide a good fit to the data at all frequencies. It is remarkable that when the synchrotron losses are taken into account, the degeneracy for the optically-thin emission between the magnetic field and the nonthermal electron density (e.g. Chevalier 1998) is lifted.

Figure 13 shows the effect of changing

![]() .

The values of the electron injection parameter are somewhat arbitrary, except for the case

.

The values of the electron injection parameter are somewhat arbitrary, except for the case

![]() .

We see that in the test-particle case (

.

We see that in the test-particle case (

![]() ), the decline of the optically-thin emission with time is too slow as compared to the data. This provides evidence that the pressure from accelerated ions is important to the structure of the blast wave. But we also see that for

), the decline of the optically-thin emission with time is too slow as compared to the data. This provides evidence that the pressure from accelerated ions is important to the structure of the blast wave. But we also see that for

![]() the light curves decline too rapidly, which shows that the shock modification is relatively weak. There is a partial correlation between

the light curves decline too rapidly, which shows that the shock modification is relatively weak. There is a partial correlation between

![]() and Bu0. By varying these two parameters and comparing the calculated curves to the data, I estimate the acceptable range for the proton injection rate to be

and Bu0. By varying these two parameters and comparing the calculated curves to the data, I estimate the acceptable range for the proton injection rate to be

![]() .

Higher values of

.

Higher values of

![]() are often used in studies of Galactic SNRs