| Issue |

A&A

Volume 497, Number 3, April III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 945 - 962 | |

| Section | Astronomical instrumentation | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811454 | |

| Published online | 18 February 2009 | |

The Large APEX BOlometer CAmera LABOCA

G. Siringo1 - E. Kreysa1 - A. Kovács1 - F. Schuller1 - A. Weiß1 - W. Esch1 - H.-P. Gemünd1 - N. Jethava2 - G. Lundershausen1 - A. Colin3 - R. Güsten1 - K. M. Menten1 - A. Beelen4 - F. Bertoldi5 - J. W. Beeman6 - E. E. Haller6

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany

2 -

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO 80305, USA

3 -

Instituto de Fisica de Cantabria (CSIC-UC), Avda. Los Castros, 39005 Santander, Spain

4 -

Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale, Bât. 121, Université Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France

5 -

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, University of Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

6 -

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

Received 1 December 2008 / Accepted 21 January 2009

Abstract

The Large APEX BOlometer CAmera, LABOCA, has been commissioned for operation as a new facility instrument

at the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment 12 m submillimeter telescope.

This new 295-bolometer total power camera, operating in the 870  m atmospheric window,

combined with the high efficiency of APEX and the excellent atmospheric transmission at the site,

offers unprecedented capability in mapping submillimeter continuum emission for a wide range of astronomical purposes.

m atmospheric window,

combined with the high efficiency of APEX and the excellent atmospheric transmission at the site,

offers unprecedented capability in mapping submillimeter continuum emission for a wide range of astronomical purposes.

Key words: instrumentation: detectors - instrumentation: photometers - submillimeter - methods: observational

1 Introduction

1.1 Astronomical motivation

Millimeter and submillimeter wavelength continuum emission

is a powerful probe of the warm and cool dust in the Universe.

For temperatures below  40 K, the peak of the thermal continuum emission is at wavelengths longer than 100

40 K, the peak of the thermal continuum emission is at wavelengths longer than 100  m

(or at frequencies lower than 3 THz), i.e. in the far-infrared and (sub)millimeter

m

(or at frequencies lower than 3 THz), i.e. in the far-infrared and (sub)millimeter![]() range.

A number of atmospheric windows between 200 GHz and 1 THz make ground-based observations possible over a large part of

this range from high-altitude, dry sites.

range.

A number of atmospheric windows between 200 GHz and 1 THz make ground-based observations possible over a large part of

this range from high-altitude, dry sites.

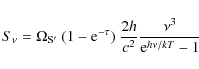

Specifically, thermal dust emission is well described by a gray body spectrum,

with the measured flux density  at frequency

at frequency  expressed as:

expressed as:

where h and k are Planck's and Boltzmann's constants respectively, c is the speed of light,

is the apparent source solid angle

(the size of the physical source convolved with the telescope beam)

and

is the apparent source solid angle

(the size of the physical source convolved with the telescope beam)

and  is the optical depth, which varies with frequency.

In the (sub)millimeter range, the emission is almost always optically thin with

is the optical depth, which varies with frequency.

In the (sub)millimeter range, the emission is almost always optically thin with

,

where

,

where  is in the range 1-2 typically

(see, e.g., the Appendix of Mezger et al. 1990; or Beuther et al. 2002, for a more thorough discussion).

Here, N is the number of dust particles (or number of nucleons assuming a given dust-to-gas

relation) in the telescope beam. Accordingly, the (sub)millimeter flux

can be converted into dust/gas masses, when the temperature T is

assumed or constrained via additional far-infrared measurements.

is in the range 1-2 typically

(see, e.g., the Appendix of Mezger et al. 1990; or Beuther et al. 2002, for a more thorough discussion).

Here, N is the number of dust particles (or number of nucleons assuming a given dust-to-gas

relation) in the telescope beam. Accordingly, the (sub)millimeter flux

can be converted into dust/gas masses, when the temperature T is

assumed or constrained via additional far-infrared measurements.

Such mass determination is one of the core issues of (sub)millimeter photometry. We would like to illustrate its paramount importance with a few examples: (sub)millimeter wavelengths mapping of low-mass star-forming regions in molecular clouds have determined the dense core mass spectrum, (in nearby regions) down to sub-stellar masses, and investigated its relationship to the Initial Mass Function (Motte et al. 1998). These studies can be extended to high-mass star-forming regions (e.g. Johnstone et al. 2006; Motte et al. 2007). Because of the larger distances to rarer, high-mass embedded objects, even relatively shallow surveys are capable of detecting pre-stellar cluster clumps with a few hundreds of solar masses of material at distances as far as the Galactic center. Masses and observed sizes yield radial density distribution profiles for protostellar cores that can be compared with theoretical models (Beuther et al. 2002).

(Sub)millimeter continuum emission is also a remarkable tool for the study of the distant Universe. The thermal dust emission in active galaxies is typically fueled by short-lived, high-mass stars, therefore the far-infrared luminosity provides a snapshot of the current level of star-formation activity. Deep (sub)millimeter observations in the Hubble Deep Field, with the Submillimeter Common User Bolometer Array (SCUBA, Holland et al. 1999) on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, attracted considerable attention with the detection of a few sources without optical or near-infrared counterpart. Sensitive measurements found dust in high redshift sources and even in some of the farthest known objects in the Universe (see, e.g., Carilli et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2008; Bertoldi et al. 2003), revealing star-formation rates (SFRs) that are hundreds of times higher than in the Milky Way today. These detections are possible because of the so-called negative K-correction first discussed by Blain & Longair (1993): the warm dust in galaxies is typically characterized by temperatures around 30-60 K. Its thermal emission dominates the spectral energy distribution (SED) of luminous and ultra-luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs and ULIRGs), which have maxima between 3 and 6 THz as a result. Because of the expansion of the Universe, the peak of the emission shifts toward the lower frequencies with increasing cosmological distance, thus counteracting the dimming and benefitting detection at (sub)millimeter wavelength. Consequently, flux-limited surveys near millimeter wavelengths yield flat or nearly flat luminosity selection over much of the volume of the Universe (Blain et al. 2002). As such, (sub)millimeter wavelengths allow unbiased studies of the luminosity evolution and, therefore, of the star-formation history of galaxies over cosmological time-scales.

1.2 Bolometer arrays for (sub)millimeter astronomy

The (sub)millimeter dust emission is unfortunately intrinsically weak and

the wish to measure it pushed the development of detectors with the best

possible sensitivity, namely bolometers (Low 1961; Mather 1984).

Moreover, the desirability of mapping large areas of the sky,

motivated the development of detector arrays.

Consequently, the last 10 years have seen an

increasing effort in the development of bolometer arrays. In such

instruments, a number of composite bolometers work side by side in the

focal plane, offering simultaneous multi-beam coverage. Since the

arrival of the first arrays, developed in the early '90s and

consisting of just 7 elements, we are witnessing a rapid maturing of

technology, reaching hundreds to a few thousand elements today, and

the prospect of even larger bolometer arrays in the future.

The Large APEX BOlometer CAmera, LABOCA, described in this article,

is a new bolometric receiver array for the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment 12 m telescope,

APEX![]() . It is the most ambitious camera in a long

line of developments of the MPIfR bolometer group, which has delivered

instruments of increasing complexity to the IRAM 30 m telescope

(Kreysa 1990): single beam receivers were supplanted by a

7-element system (Kreysa et al. 1999), which eventually gave way to the

MAx-Planck Millimeter BOlometer (MAMBO) array, whose initial 37 beams

have grown to 117 in the latest incarnation (Kreysa et al. 2002).

The group also built the 37-element 1.2 mm SEST Imaging Bolometer Array (SIMBA)

for the Swedish/ESO Submillimeter telescope (Nyman et al. 2001)

and the 19-element 870

. It is the most ambitious camera in a long

line of developments of the MPIfR bolometer group, which has delivered

instruments of increasing complexity to the IRAM 30 m telescope

(Kreysa 1990): single beam receivers were supplanted by a

7-element system (Kreysa et al. 1999), which eventually gave way to the

MAx-Planck Millimeter BOlometer (MAMBO) array, whose initial 37 beams

have grown to 117 in the latest incarnation (Kreysa et al. 2002).

The group also built the 37-element 1.2 mm SEST Imaging Bolometer Array (SIMBA)

for the Swedish/ESO Submillimeter telescope (Nyman et al. 2001)

and the 19-element 870  m for the 10 m Heinrich-Hertz Telescope

(a.k.a. SMTO, Martin & Baars 1990).

m for the 10 m Heinrich-Hertz Telescope

(a.k.a. SMTO, Martin & Baars 1990).

The main obstacle to observations at these wavelengths is posed by Earth's atmosphere, which is seen as a bright emitting screen by a continuum total power detector, as LABOCA's bolometers are. This is largely due to the emission of the water vapor present in the atmosphere with only small contributions from other components, like ozone. Besides, the atmosphere is a turbulent thermodynamic system and the amount of water vapor along the line of sight can change quickly, giving rise to instabilities of emission and transmission, called sky noise. Observations from ground based telescopes have to go through that screen, therefore requiring techniques to minimize those effects.

The technique most widely used is to operate a switching device, usually a chopping secondary mirror (hereafter called wobbler) to observe alternatively the source and a blank sky area close to it, at a frequency higher than the variability scale of the sky noise. This method, originally introduced for observations with single pixel detectors, is today also used with arrays of bolometers. Although it can be very efficient to reduce the atmospheric disturbances during observations, it presents some disadvantages: among others, the wobbler is usually slow (1 or 2 Hz) posing a strong limitation to the possible scanning speed.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm, bb=0 0 1260 1260, clip]{1454fig01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg14.png) |

Figure 1: Wiring side of a naked LABOCA array. Each light-green square is a bolometer. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

LABOCA has been specifically designed to work without a wobbler and using a different technique, which works particularly well when using an array of detectors, to remove the atmospheric contribution. This technique, called fast scanning (Reichertz et al. 2001), is based on the idea that, when observing with an array, the bolometers composing the array look simultaneously at different points in the sky, therefore chopping is no more needed. A modulation of the signal, still required to identify the astronomical source through the atmospheric emission, is produced by scanning with the telescope across the source. The atmospheric contribution (as well as part of the instrumental noise) will be strongly correlated in all bolometers and a post-detection analysis of the correlation across the array will make it possible to extract the signals of astronomical interest from the atmospheric foregrounds. Moreover, the post-detection bandwidth depends on the scanning speed, therefore relatively high scanning speeds are ideal (see also Kovács 2008).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{1454fig02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg15.png) |

Figure 2: Scheme of the infrastructure of LABOCA. The instrument is located in the Cassegrain cabin (dashed red line) of APEX, remote operation is a requirement and all the communication goes through the local area network (magenta arrows) and a direct Ethernet link between backend and bridge computers. The black lines show the flow of the bolometer signals, the orange ones show the configuration and monitoring communication. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The APEX telescope (Güsten et al. 2006), as the name implies, serves as a pathfinder for the future large-scale (sub)millimeter wavelength and (far)infrared missions, namely the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), the Herschel Space Observatory and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA). Its pathfinder character is on the one hand defined by exploring wavelength windows that have been poorly studied before, with acceptable atmospheric transmission at the 5100 m altitude site. On the other hand, and more importantly, it can perform large area mapping to identify interesting sources for ALMA follow-up studies at higher angular resolution. Moreover, APEX produces images of both continuum (with LABOCA) and line emission with angular resolutions that neither Herschel's nor SOFIA's smaller telescopes (with diameters of 3.5 and 2.5 m respectively) can match. This provides a critical advantage to APEX for imaging dust and line emission at high frequencies.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm, bb= 0 0 3149 2306,clip]{1454fig03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg16.png) |

Figure 3: Overview of the optics. On the left, the APEX telescope. On the right, a zoom on the tertiary optics installed in the Cassegrain cabin. See also Fig. 4. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

1.3 Instrument overview

LABOCA is an array of bolometers, operated in total-power mode, specifically designed for fast mapping of large areas of sky at moderate resolution and with high sensitivity and was commissioned in May 2007 as facility instrument on APEX. It is a very complex system, composed of parts that originate in a variety of fields of technology, in particular optics, high vacuum, low temperature cryogenics, digital electronics, computer hardware and software, and others. A general view of the infrastructure is shown in the block diagram of Fig. 2. The heart of LABOCA is its detector array made of 295 semiconducting composite bolometers (see Figs. 1, 6). A description of the detector array design and manufacture is provided in Sect. 5.

The bolometer array is mounted in a cryostat, which uses liquid

nitrogen and liquid helium on a closed cycle double-stage sorption

cooler to reach an operation temperature of  285 mK. The

cryogenic system is discussed in Sect. 3.

285 mK. The

cryogenic system is discussed in Sect. 3.

A set of cold filters, mounted on the liquid nitrogen and liquid

helium shields, define the spectral passband, centered at a wavelength

of 870  m and about 150

m and about 150  m wide (see

Fig. 5). A monolithic array of conical horn

antennas, placed in front of the bolometer wafer, concentrates the

radiation onto the individual bolometers. The filters and the horn

array are presented in Sect. 4.

m wide (see

Fig. 5). A monolithic array of conical horn

antennas, placed in front of the bolometer wafer, concentrates the

radiation onto the individual bolometers. The filters and the horn

array are presented in Sect. 4.

The cryostat is located in the Cassegrain cabin of the APEX telescope (see Fig. 4) and the optical coupling to the telescope is provided by an optical system made of a series of metal mirrors and a lens which forms the cryostat window. The complex optics layout, manufacture and installation at the telescope is described in Sect. 2.

The bolometer signals are routed through low noise, unity gain Junction Field Effect Transistor (JFET) amplifiers and to the outside of the cryostat along flexible flat cables. Upon exiting the cryostat, the signals pass to room temperature low noise amplifiers and electronics also providing the AC current for biasing the bolometers and performing real time demodulation of the signals. The signals are then digitized over 16 bits by 4 data acquisition boards providing 80 analog inputs each, mounted in the backend computer. The backend software provides an interface to the telescope's control software, used to set up the hardware, and a data server for the data output. The acquired data are then digitally filtered and downsampled to a lower rate in real time by the bridge computer and finally stored in MB-FITS format (Muders et al. 2006) by the FITS writer embedded in the telescope's control software. Another computer, the frontend computer, is devoted to monitor and control most of the electronics embedded into the receiver (e.g. monitoring of all the temperature stages, controlling of the sorption cooler, calibration unit) and provides an interface to the APEX control software, allowing remote operation of the system. Discussions of the cold and warm readout electronics, plus the signal processing, are found in Sects. 6 and 7, respectively.

In Sect. 8 we describe the sophisticated observing techniques used with LABOCA, some of them newly developed. The instrument performance on the sky is described in Sect. 9, along with information on sensitivity, beam shape and noise behavior.

The reduction of the data is performed using a new data reduction software included in the delivery of LABOCA as facility instrument, the BoA (Bolometer array data Analysis) data reduction software package. An account of on-line and off-line data reduction is given in Sect. 10.

Some of the exciting science results already obtained with LABOCA or expected in the near future are outlined in Sect. 11. Our plans for LABOCA's future are briefly presented in Sect. 12.

2 Tertiary optics

2.1 Design and optimization

The very restricted space in the Cassegrain cabin of

APEX and a common first mirror (M3) with the APEX SZ Camera

(ASZCa, Schwan et al. 2003) introduced many boundary

conditions into the optical design. Eventually, with the help of the

ZEMAX![]() optical design program, a

satisfactory solution was found, featuring three aspherical off-axis

mirrors (M3, M5, M7), two plane mirrors (M4, M6) and an aspherical

lens acting as the entrance window of the cryostat (see

Fig. 3). Meeting the spatial constraints, without

sacrificing optical quality, is facilitated considerably by the

addition of plane mirrors.

The design of the optics was made at the MPIfR in coordination with N. Halverson

optical design program, a

satisfactory solution was found, featuring three aspherical off-axis

mirrors (M3, M5, M7), two plane mirrors (M4, M6) and an aspherical

lens acting as the entrance window of the cryostat (see

Fig. 3). Meeting the spatial constraints, without

sacrificing optical quality, is facilitated considerably by the

addition of plane mirrors.

The design of the optics was made at the MPIfR in coordination with N. Halverson![]() with respect to sharing the large M3 mirror

with the ASZCa experiment.

with respect to sharing the large M3 mirror

with the ASZCa experiment.

The maximum possible field diameter of APEX, as limited by the

diameter of the Cassegrain hole of the telescope's primary, is about

0.5 degrees. LABOCA, with its 295 close-packed fully efficient horns,

covers an almost circular field of view (hereafter FoV) of about 0.2

degrees in diameter (or about 100 square arcminutes). The task of the

tertiary optics is to transform the f-ratio from f/8 at the Cassegrain

focus to f/1.5 at the horn array, while correcting the aberrations

over the whole FoV of LABOCA under the constraint of parallel output

beams. The final design is diffraction limited even for 350  m

wavelength, the Strehl ratio is better than 0.994 and the maximum

distortion at the focal plane is less than 10% over the entire FoV

(see also Fig. 10).

m

wavelength, the Strehl ratio is better than 0.994 and the maximum

distortion at the focal plane is less than 10% over the entire FoV

(see also Fig. 10).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,bb=0 -5 538 375, clip]{1454fig04...

...ludegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=0 0 540 720,clip]{1454fig04bottom.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg17.png) |

Figure 4: Top: the mirrors affixed to the floor of the Cassegrain cabin of APEX. Left to right: M7, M5, M3 and one of the mirrors of the ASZCa experiment. In this picture, mirror M3 is positioned for ASZCa. Bottom: the receiver, M3 in the position for LABOCA, M5, M6 and M7. See also Fig. 3. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 Manufacture

Mirror M3, an off-axis paraboloid, has been

manufactured by a machine shop at the Lawrence Berkeley National

Laboratory (LBNL, Berkeley, CA, USA) and is common to both LABOCA and the ASZCa

experiment. M3 has a diameter of 1.6 m and a surface accuracy of

18  m rms but LABOCA uses only the inner 80 cm disk. It is

attached to a bearing on the floor of the Cassegrain cabin, aligned to

the optical axis of APEX. Operators can manually rotate the mirror in

order to direct the telescope beam to LABOCA or to ASZCa alternatively

(see Fig. 4).

m rms but LABOCA uses only the inner 80 cm disk. It is

attached to a bearing on the floor of the Cassegrain cabin, aligned to

the optical axis of APEX. Operators can manually rotate the mirror in

order to direct the telescope beam to LABOCA or to ASZCa alternatively

(see Fig. 4).

Mirrors M4 and M6 are flat, have a diameter of 42 cm and 26 cm,

respectively (manufactured by Kugler![]() , Salem, Germany).

They are of optical quality and are both affixed to the ceiling of the cabin.

In a near future, mirror M6 will be replaced by the reflection-type half-wave

plate of the PolKa polarimeter (Siringo et al. 2004).

, Salem, Germany).

They are of optical quality and are both affixed to the ceiling of the cabin.

In a near future, mirror M6 will be replaced by the reflection-type half-wave

plate of the PolKa polarimeter (Siringo et al. 2004).

Mirrors M5 and M7 are off-axis aspherics, both 50 cm in diameter, and

are affixed to the floor of the cabin. They have been designed and

manufactured at the MPIfR and have a surface accuracy of 7 and

5  m rms respectively.

m rms respectively.

2.3 Installation and alignment

All the mirrors of LABOCA

(with exception of M3) and the receiver itself are mounted on hexapod positioners (see Fig. 4)

provided by VERTEX Antennentechnik![]() (Duisburg, Germany).

Each hexapod is made of an octahedral assembly of struts and has six degrees of freedom (x, y, z, pitch,

roll and yaw). The lengths of the six independent legs can be changed

to position and orient the platform on which the mirror is mounted.

VERTEX provided a software for calculating the required leg extensions

for a given position and orientation of the platforms.

A first geometrical alignment was performed during the first week of September

2006, using a double-beam laser on the optical axis of the telescope

and plane replacement mirrors in place of the two active mirrors M5

and M7. The alignment has been checked using the bolometers and hot

targets (made of absorbing

(Duisburg, Germany).

Each hexapod is made of an octahedral assembly of struts and has six degrees of freedom (x, y, z, pitch,

roll and yaw). The lengths of the six independent legs can be changed

to position and orient the platform on which the mirror is mounted.

VERTEX provided a software for calculating the required leg extensions

for a given position and orientation of the platforms.

A first geometrical alignment was performed during the first week of September

2006, using a double-beam laser on the optical axis of the telescope

and plane replacement mirrors in place of the two active mirrors M5

and M7. The alignment has been checked using the bolometers and hot

targets (made of absorbing![]() material)

at different places along the beam, starting at the focal plane and

following the path through all the reflections up to the receiver's

window. The alignment has been furthermore verified and improved in

February 2008.

material)

at different places along the beam, starting at the focal plane and

following the path through all the reflections up to the receiver's

window. The alignment has been furthermore verified and improved in

February 2008.

3 Cryogenics

3.1 Cryostat

The bolometer array of LABOCA is designed to be operated at a temperature

lower than 300 mK. This temperature is provided by a cryogenic

system made of a wet cryostat, using liquid nitrogen and liquid

helium, in combination with a two-stage sorption cooler. A commercial

8-inch cryostat, built by Infrared Labs![]() (Tucson, AZ, USA), has been

customized at the MPIfR to accommodate the double-stage sorption

cooler, the bolometer array, cold optics and cold electronics. A high

vacuum in the cryostat is provided by an integrated turbomolecular

pump backed by a diaphragm pump. Operational vacuum is reached in one

single day of pumping.

(Tucson, AZ, USA), has been

customized at the MPIfR to accommodate the double-stage sorption

cooler, the bolometer array, cold optics and cold electronics. A high

vacuum in the cryostat is provided by an integrated turbomolecular

pump backed by a diaphragm pump. Operational vacuum is reached in one

single day of pumping.

The cryostat incorporates a 3-liter reservoir of liquid nitrogen and a

5-liter reservoir of liquid helium. After producing high-vacuum

( 10-6 mbar), the cryostat is filled with the liquid

cryogens. The liquid nitrogen is used to provide thermal shielding at

77 K in our labs in Bonn (standard air pressure, 1013 mbar) and at

73.5 K at APEX (5107 m above the sea level) where the air pressure

is almost one half of the standard one (about 540 mbar).

10-6 mbar), the cryostat is filled with the liquid

cryogens. The liquid nitrogen is used to provide thermal shielding at

77 K in our labs in Bonn (standard air pressure, 1013 mbar) and at

73.5 K at APEX (5107 m above the sea level) where the air pressure

is almost one half of the standard one (about 540 mbar).

The liquid helium provides a thermal shielding at 4.2 K at standard pressure and 3.7 K at the APEX site. To keep it operational, the system must be refilled once per day. The refilling operation requires about 20 min.

3.2 Sorption cooler

The cryostat incorporates a commercial two-stage closed-cycle sorption

cooler, model SoCool (Duband et al. 2002) manufactured by

Air-Liquide![]() (Sassenage,

France). In this device, a 4He sorption cooler is used to

liquefy 3He gas in the adjacent, thermally coupled, 3He

cooler. The condensed liquid 3He is then sorption pumped to

reach temperatures as low as 250 mK, in the absence of a thermal

load. Therefore, the double stage design makes it possible to cool the

bolometer array down to a temperature lower than 300 mK starting from the

temperature of the liquid helium bath at atmospheric pressure. This

makes the maintenance of the system much simpler than that of other

systems, where pumping on the liquid helium bath is required. The two

sorption coolers are closed systems, which means they do not require

any refilling of gas and can be operated from the outside of the

cryostat, simply by applying electrical power.

(Sassenage,

France). In this device, a 4He sorption cooler is used to

liquefy 3He gas in the adjacent, thermally coupled, 3He

cooler. The condensed liquid 3He is then sorption pumped to

reach temperatures as low as 250 mK, in the absence of a thermal

load. Therefore, the double stage design makes it possible to cool the

bolometer array down to a temperature lower than 300 mK starting from the

temperature of the liquid helium bath at atmospheric pressure. This

makes the maintenance of the system much simpler than that of other

systems, where pumping on the liquid helium bath is required. The two

sorption coolers are closed systems, which means they do not require

any refilling of gas and can be operated from the outside of the

cryostat, simply by applying electrical power.

To keep the bolometers at operation temperature, the sorption cooler

needs to be recycled. The recycling is done by application of a

sequence of voltages to the electric lines connected to thermal

switches and heaters integrated in the sorption cooler. A typical

recycling procedure requires about two hours and can be done manually

or in a fully automatic way controlled by the frontend computer (see

Sect. 7.4). At the end of the recycling process, both

gases, 4He and 3He, have been liquefied and the controlled

evaporation of the two liquids provides a stable temperature for many

hours. After the recycling of the sorption cooler, the bolometer

array reaches 285 mK. The hold time of the cooler, usually between

10 and 12 h, strongly depends on the parameters used during the

recycling procedure.

The end temperature is a function of elevation and can be affected by telescope movements,

leading to temperature fluctuations  500

500  K within one scan,

during regular observations, and

K within one scan,

during regular observations, and  3 mK for wide elevation turns

(e.g. during skydips, see Sect. 8.2.3).

3 mK for wide elevation turns

(e.g. during skydips, see Sect. 8.2.3).

3.3 Temperature monitor

The cryostat of LABOCA incorporates 8

thermometers to measure the temperature at the different stages:

liquid nitrogen, liquid helium, the two sorption pumps, the two

thermal switches, evaporator of the 4He and evaporator of the

3He. Two LS218![]() devices (Lake Shore Inc., Westerville, OH, USA) are used to monitor the thermometers

and to apply the individual temperature calibrations in real-time.

The temperature of the 3He stage is measured with higher accuracy with the use of a

resistance bridge AVS-47

devices (Lake Shore Inc., Westerville, OH, USA) are used to monitor the thermometers

and to apply the individual temperature calibrations in real-time.

The temperature of the 3He stage is measured with higher accuracy with the use of a

resistance bridge AVS-47![]() (Picowatt, Vantaa, Finland), with an error of

(Picowatt, Vantaa, Finland), with an error of  5

5  K .

Control and monitor of the cryogenic

equipment can be done remotely via the frontend computer (see

Sect. 7.4).

K .

Control and monitor of the cryogenic

equipment can be done remotely via the frontend computer (see

Sect. 7.4).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=114 90 768 525, clip]{1454fig05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg20.png) |

Figure 5: Spectral response of LABOCA, relative to the maximum. The central frequency is 345 GHz, the portion with 50% or more transmission is between 313 and 372 GHz. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Cold optics

4.1 Passband definition

Inside the cryostat, a set of cold filters, mounted on

the liquid nitrogen and liquid helium shields define the spectral

passband, centered at a wavelength of 870  m (345 GHz) and about

150

m (345 GHz) and about

150  m (60 GHz) wide (see Fig. 5). The filters

have been designed and manufactured at MPIfR in collaboration with the

group of V. Hansen (Theoretische Elektrotechnik

m (60 GHz) wide (see Fig. 5). The filters

have been designed and manufactured at MPIfR in collaboration with the

group of V. Hansen (Theoretische Elektrotechnik![]() , Bergische

Universität Wuppertal, Germany) who provided theoretical support and

electromagnetic simulations. The passband is formed by an

interference filter made of inductive and capacitive meshes embedded

in polypropylene. The low frequency edge of the band is defined by

the cut-off of the cylindrical waveguide of each horn antenna (see

also Sect. 4.2). A freestanding inductive mesh behind the

window-lens provides shielding against radio interference.

, Bergische

Universität Wuppertal, Germany) who provided theoretical support and

electromagnetic simulations. The passband is formed by an

interference filter made of inductive and capacitive meshes embedded

in polypropylene. The low frequency edge of the band is defined by

the cut-off of the cylindrical waveguide of each horn antenna (see

also Sect. 4.2). A freestanding inductive mesh behind the

window-lens provides shielding against radio interference.

4.2 Horn array

A monolithic array of conical

horn antennas, placed in front of the bolometer wafer, concentrates

the radiation onto the bolometers. 295 conical horns have been

machined into a single aluminum block by the MPIfR machine shop. In

combination with the tertiary optics, the horn antennas are optimized

for coupling to the telescope's main beam at a wavelength of

870  m

m ![]() .

The grid constant of the hexagonal array is

4.00 mm. Each horn antenna feeds into a circular wave guide with a

diameter of 0.54 mm, acting as a high-pass filter.

.

The grid constant of the hexagonal array is

4.00 mm. Each horn antenna feeds into a circular wave guide with a

diameter of 0.54 mm, acting as a high-pass filter.

5 Detector

5.1 Array design and manufacture

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm, bb= 0 0 277 277, clip]{1454...

...degraphics[width=6cm, bb= 0 0 192 192, clip]{1454fig06right.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg22.png) |

Figure 6: Pictures of the bolometer array of LABOCA. Left: a detail of the array mounted in its copper ring. Some bonding wires are visible. Center: the side of the array where the bolometer cavities are etched in the silicon wafer. Right: wiring side of the array. The thermistors are visible as small cubes on the membranes. One broken membrane is visible on the top left corner. See also Fig. 1. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The bolometer array of LABOCA is made of 295 composite bolometers arranged in an hexagonal

layout consisting of a center channel and 9 concentric hexagons (see Figs. 1

and 6). The array is manufactured on a 4-inch silicon wafer coated on both sides with

a silicon-nitride film by thermal chemical vapor deposition. On one side of the wafer,

295 squares are structured into the silicon-nitride film used as a mask for the alkaline KOH

etching of the silicon, producing freestanding, unstructured silicon-nitride membranes, only

400 nm thick (see the center picture in Fig. 6).

On the other side, the wiring is created by microlithography of

niobium and gold thin metal layers. The bolometer array is mounted

inside a gold-coated copper ring and is supported by about 360 gold

bonding thin wires (see Fig. 6, left), providing the

required electrical and thermal connection. This copper ring

also serves as a mount for the backshort reflector, at  /4 distance from

the array, and 12 printed circuit boards hosting the load resistors

and the first electronic circuitry (see Sect. 6).

/4 distance from

the array, and 12 printed circuit boards hosting the load resistors

and the first electronic circuitry (see Sect. 6).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=15 20 936 630, clip]{1454fig07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg24.png) |

Figure 7: Wiring side of one bolometer of LABOCA, seen under a microscope. The membrane is the green colored area. The black box is the NTD thermistor. The wiring is made of gold (yellow) and niobium (gray) thin metal layers. See also Fig. 6. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Bolometer design and manufacture

The description of a composite bolometer can be simplified as the combination of two elements: an extremely sensitive temperature sensor, called thermistor, and a radiation absorber. In the bolometers of LABOCA, the absorbing element is made of a thin film of titanium deposited on the unstructured silicon-nitride membranes. LABOCA uses neutron-transmutation doped germanium semiconducting chips (NTD, Haller et al. 1982) as thermistors. The NTD thermistors are made from ultra-pure germanium doped by neutron-transmutation in a nuclear reactor. The thermistors, needed to measure the temperature of the absorber, are soldered on the bolometer membranes to gold pads connected to the outer edge of the silicon wafer through a pair of patterned niobium wires, superconducting at the operation temperature (see Figs. 7 and 6, right). The soldering of the thermistors was the only manual step in the manufacture of the bolometers. LABOCA has so-called flatpack NTD thermistors, which have two ion implanted and metalized contacts on one side of the thermistor block. The chips are optimized to work at a temperature lower than 300 mK, where they show an electric impedance in the range of 1 to 10 MOhms.

6 Cold electronics

6.1 Bias resistors

Given the high impedance of the NTD thermistors, the electric scheme

of the first bolometer circuitry requires very high impedance load

resistors, which are needed to current bias the bolometers. These

bias resistors are 312 identical 30 MOhm chips, made of a nichrome

thin film deposited on silicon substrate (model MSHR-4 produced by

Mini-Systems Inc.![]() ,

N. Attleboro, MA, USA) mounted on 12 identical printed circuit boards, to

form 12 groups of 26 resistors. This configuration is reflected in the

following distribution of the bolometer signals. The circuit boards

are mounted on the same copper ring which holds the bolometer array

(see Sect. 5.1)

and electrically connected to the bolometers through miniature RF

filters.

,

N. Attleboro, MA, USA) mounted on 12 identical printed circuit boards, to

form 12 groups of 26 resistors. This configuration is reflected in the

following distribution of the bolometer signals. The circuit boards

are mounted on the same copper ring which holds the bolometer array

(see Sect. 5.1)

and electrically connected to the bolometers through miniature RF

filters.

6.2 Junction field effect transistors (JFETs) source followers

The high impedance of the bolometers makes the system

sensitive to microphonic noise pickup, therefore JFETs (Toshiba 2SK369)

are used as source followers in order to decrease the impedance of the

electric lines down to a few kOhms before they reach the high gain

amplification units at room temperature. Following the wiring scheme

of the bias resistors, the JFETs are also in groups of 26 soldered

onto 12 printed circuit boards, electrically connected to the

corresponding bias resistors by 12 flat cables made of manganin traces embedded in

Kapton![]() (manufactured by VAAS Leiterplattentechnologie

(manufactured by VAAS Leiterplattentechnologie![]() ,

Schwäbisch-Gmünd, Germany), thermally shunted to the liquid helium tank.

The 12 JFET boards are assembled in groups of

three into four gold-coated copper boxes, thermally connected to the

liquid nitrogen tank. Inside each box, during regular operation, the

78 JFETs are self-heated to a temperature of about 110 K, where they

show a minimum of their intrinsic noise. Through the connections in

the JFET boxes, the wiring scheme of 12 groups of 26 channels is

translated to a new scheme of 4 groups of 80 channels.

,

Schwäbisch-Gmünd, Germany), thermally shunted to the liquid helium tank.

The 12 JFET boards are assembled in groups of

three into four gold-coated copper boxes, thermally connected to the

liquid nitrogen tank. Inside each box, during regular operation, the

78 JFETs are self-heated to a temperature of about 110 K, where they

show a minimum of their intrinsic noise. Through the connections in

the JFET boxes, the wiring scheme of 12 groups of 26 channels is

translated to a new scheme of 4 groups of 80 channels.

7 Warm electronics and signal processing

7.1 Amplifiers

The 312 channels exiting the cryostat of LABOCA are distributed to 4 identical, custom made, amplification units, providing 80 channels each. Of these, 295 are bolometers, 17 are connected to 1 MOhm resistors mounted on the bolometer ring (used for technical purposes, like noise monitoring and calibrations) and the remaining 8 are not connected. Each amplification unit is made of 16 identical printed circuit boards and each board provides 5 low noise, high gain amplifiers. Each unit also includes a low noise battery used to generate the bias voltage and the circuitry to produce the AC biasing and perform real time demodulation of the 320 signals. The AC bias reference frequency is not internally generated but is provided from the outside, thus allowing synchronization of the biasing to an external frequency source.

Each amplification unit is equipped with a digital interface controlled by a microprocessor programmed to provide remote control of

the amplification gain and of the DC offset removal procedure. This is required because LABOCA is a total power receiver and the

signals carry a floating DC offset which could exceed the dynamic range of the data acquisition system.

To avoid saturation, therefore, the DC offsets are measured and subtracted from the signals at the beginning of every integration.

The values of the 320 offsets are temporarily stored in a local memory and, at the end of the observation, are written into the

corresponding data file for use in the data reduction process.

The digital lines use the I2C protocol![]() and are accessible remotely via the local network through I2C-to-RS232

and are accessible remotely via the local network through I2C-to-RS232![]() interfaces controlled by the frontend computer (see Sect. 7.4).

The amplification gain can be set in the range from 270 to 17 280.

interfaces controlled by the frontend computer (see Sect. 7.4).

The amplification gain can be set in the range from 270 to 17 280.

7.2 Data acquisition

The 320 output signals from the 4 amplification units are digitized over 16 bits by 4 multifunction data acquisition (DAQ) boards

(National Instruments![]() M-6225-PCI),

providing 80 analog inputs each and synchronized to the same sample

clock by a RTSI

M-6225-PCI),

providing 80 analog inputs each and synchronized to the same sample

clock by a RTSI![]() bus . The maximum data

sampling is 2500 Hz and the dynamic range can be selected over 5

predefined ranges. The four boards provide also 24 digital

input/output lines each, some of them used for the generation of the

bias reference frequency and to monitor the digital reference signals

(sync/blank) of the wobbler. For the time synchronization of the data

to the APEX control software (APECS, Muders et al. 2006) the

data acquisition system is equipped with a precision time interface

(PCI-SyncClock32

bus . The maximum data

sampling is 2500 Hz and the dynamic range can be selected over 5

predefined ranges. The four boards provide also 24 digital

input/output lines each, some of them used for the generation of the

bias reference frequency and to monitor the digital reference signals

(sync/blank) of the wobbler. For the time synchronization of the data

to the APEX control software (APECS, Muders et al. 2006) the

data acquisition system is equipped with a precision time interface

(PCI-SyncClock32![]() from Brandywine Communications, Tustin, CA, USA)

synchronized to the station GPS clock via

IRIG-B

from Brandywine Communications, Tustin, CA, USA)

synchronized to the station GPS clock via

IRIG-B![]() time code signal.

time code signal.

The AC bias reference frequency is provided by the data acquisition system as a submultiple of the sampling frequency, thus synchronizing the bias to the data sampling. Typical values used for observations are 1 kHz for the sampling rate and 333 Hz for the AC bias. The backend computer has two network adapters: one is connected to the local area network, the other one is exclusively used for the output data stream and is connected in a private direct network with the bridge computer (see also Sect. 7.3).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=0 0 726 551,clip]{1454fig08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg25.png) |

Figure 8:

Noise spectra for selected bolometers on a room temperature absorber (capped optics).

The signals, sampled at 1 kHz, were downsampled in real-time to 25 Hz by the bridge computer.

The spectra are free of microphonic pick-ups and show the 1/f noise onset at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The data acquisition software is entirely written using

LabVIEW![]() (National Instruments).

The drivers for the data acquisition hardware are provided by the NI-DAQmx

(National Instruments).

The drivers for the data acquisition hardware are provided by the NI-DAQmx![]() package.

Custom drivers for LabVIEW have been developed to access the GPS clock interface.

The backend software runs a server to stream the output data to the bridge computer and allows remote control

and monitoring of the operation via a CORBA

package.

Custom drivers for LabVIEW have been developed to access the GPS clock interface.

The backend software runs a server to stream the output data to the bridge computer and allows remote control

and monitoring of the operation via a CORBA![]() object interfaced

to the APECS through the local area network.

object interfaced

to the APECS through the local area network.

7.3 Anti-aliasing filtering and downsampling

The amplification units of LABOCA use the bias signal, which is a square waveform,

as reference to operate real-time demodulation of the AC-biased bolometer signals.

Therefore, all the frequencies present in the bolometer readout lines end up aliased

around the odd-numbered harmonics of the bias frequency. Microphonics pickup by the

high-impedance bolometers at a few resonant frequencies can produce a forest of lines in

the final readout, polluting even the lower part of the post-detection frequency band,

where the astronomical signals are expected.

To overcome this, we introduced an intermediate stage into the

sampling scheme, the so-called bridge computer. The bolometer

signals, acquired by the backend at a relatively high sampling rate

(usually 1 kHz), well above the rolling-off of the anti-alias filters

embedded in the amplifiers, are sent to the bridge computer where they

are digitally low-pass filtered and then downsampled to a much lower

rate (usually 25 Hz), more appropriate for the astronomical signals

produced at the typical scanning speeds (see also

Sect. 8). The digital real-time anti-alias filtering

and downsampling is performed by a non-recursive convolution filter

with a Nutall window such that its rejection at the Nyquist frequency

is  3 dB and falls steeply to

3 dB and falls steeply to  100 dB soon beyond that.

The bias reference frequency was accordingly selected to maximize the

astronomically useful post-detection bandwidth. The resulting

bolometer signals are generally white between 0.1-12.5 Hz and free

of unwanted microphonic interference (see Fig. 8).

100 dB soon beyond that.

The bias reference frequency was accordingly selected to maximize the

astronomically useful post-detection bandwidth. The resulting

bolometer signals are generally white between 0.1-12.5 Hz and free

of unwanted microphonic interference (see Fig. 8).

To seamlessly integrate the bridged readout into the APEX control system, the bridge computer also acts as a fully functional virtual backend that forwards all communication between the actual backend computer and the control system, while intercepting and reinterpreting any commands of interest for the downsampling scheme.

7.4 Frontend computer

The so-called frontend computer communicates with the hardware of LABOCA through the local area network. It is devoted to monitor and control most of the electronics of the instrument (e.g. monitoring of all the temperature stages, control of the sorption cooler, calibration unit, power lines...) and also provides a CORBA object for interfacing to APECS, allowing remote operation of the system. The frontend software is entirely written using LabVIEW and custom drivers have been developed for some hardware devices embedded in LABOCA.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, bb=33 3 259 420, clip]{1454fig09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg26.png) |

Figure 9:

Examples of raster-spiral patterns. The two plots show the scanning pattern of the central beam

of the array in horizontal coordinates. The compact pattern shown in

the top panel is optimized to map the field of view of LABOCA.

The large scale map shown in the bottom panel consists of 25 raster

positions and covers a field of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

8 Observing modes

8.1 Mapping modes

In order to reach the best signal-to-noise ratio using the fast scanning technique (Reichertz et al. 2001)

with LABOCA, the frequencies of the signal produced by scanning across the source need to match the white noise part of

the post-detection frequency band (0.1-12.5 Hz, see Fig. 8), mostly above the frequencies of the

atmospheric fluctuations. Thus, with the  19'' beam (see Sect. 9.3),

the maximum practical telescope scanning speed for LABOCA is about 4'/s.

This is also the limiting value to guarantee the required accuracy in the telescope position information of each sample.

The minimum scanning speed required for a sufficient source modulation depends on the atmospheric stability and

on the source structure and is typically about 30''/s.

The APEX control system currently supports two basic scanning modes: on-the-fly maps (OTF) and spiral scanning patterns.

19'' beam (see Sect. 9.3),

the maximum practical telescope scanning speed for LABOCA is about 4'/s.

This is also the limiting value to guarantee the required accuracy in the telescope position information of each sample.

The minimum scanning speed required for a sufficient source modulation depends on the atmospheric stability and

on the source structure and is typically about 30''/s.

The APEX control system currently supports two basic scanning modes: on-the-fly maps (OTF) and spiral scanning patterns.

8.1.1 Spirals

Spirals are done with a constant angular speed and an increasing radius, therefore the linear scanning velocity

is not constant but increases with time. We have selected two spiral modes of 20 s and 35 s integration time,

both producing fully sampled maps of the whole FoV with scanning velocities limited between 1'/s and

/s.

The spiral patterns are kept compact (maximum radius

/s.

The spiral patterns are kept compact (maximum radius

), the scanned area on the sky is only slightly

larger than the FoV and most of the integration time is spent on the central 11' of the array.

These spirals are the preferred observing modes for pointing scans on sources with flux densities down to a few Jy.

), the scanned area on the sky is only slightly

larger than the FoV and most of the integration time is spent on the central 11' of the array.

These spirals are the preferred observing modes for pointing scans on sources with flux densities down to a few Jy.

For fainter sources, the basic spiral pattern can be combined with a raster mapping mode (raster-spirals) on a grid of pointing positions resulting in an even denser sampling of the maps and longer integration time (see Fig. 9, top panel). These compact raster-spirals give excellent results for sources smaller than the FoV of LABOCA and are also suitable for integrations of very faint sources.

The flexibility in the choice of the spiral parameters also allows spiral

observing patterns to be used to map fields much larger than the FoV.

The bottom panel of Fig. 9 shows an example of

raster of spirals optimized to give an homogeneous coverage across

a field of

degrees. In this case, the spirals start

with a large radius and follows an almost circular scanning pattern

for each raster position. This mapping mode is very useful for

cosmological deep field surveys since co-adding several such

raster-spiral scans, taken at different times and thus at different

orientations, provides an optimal compromise between telescope

overheads, uniform coverage and cross-linking of individual map

positions (see Kovács 2008).

degrees. In this case, the spirals start

with a large radius and follows an almost circular scanning pattern

for each raster position. This mapping mode is very useful for

cosmological deep field surveys since co-adding several such

raster-spiral scans, taken at different times and thus at different

orientations, provides an optimal compromise between telescope

overheads, uniform coverage and cross-linking of individual map

positions (see Kovács 2008).

8.1.2 On-the-fly maps (OTF)

OTF scans are rectangular scanning patterns produced moving

back-and-forth along alternating rows with a linear constant speed and

accelerating only at the turnarounds. They can be performed in

horizontal or equatorial coordinates and the scanning direction can be

rotated relatively to the base system for both coordinate systems. OTF

patterns have been tested for maps on the scales of the FoV up to long

slews across the plane of the Milky Way (2 degrees). Small

cross-linked OTFs (of size  FoV of LABOCA) give results

comparable to the raster-spirals (Kovács 2008), but the

overheads are much larger at a scanning speed of 2'/s. For larger

OTFs the relative overheads decrease.

FoV of LABOCA) give results

comparable to the raster-spirals (Kovács 2008), but the

overheads are much larger at a scanning speed of 2'/s. For larger

OTFs the relative overheads decrease.

8.2 Ancillary modes

8.2.1 Point

The standard pointing procedure consists of one subscan in spiral observing mode and results in a fully sampled map of the FoV of LABOCA. The pointing offsets relative to the pointing model are computed via a two-dimensional Gaussian fit to the source position in the map using a BoA pipeline script (see Sect. 10). Note that this pointing procedure is not limited to pointing scans of the central channel of the array but works independently of the reference bolometer, thus allowing pointing scans centered on the most sensitive part of the array.

8.2.2 Focus

The default focusing procedure is made of 10 subscans at 5 different subreflector positions and 5 s of integration time each. This is the only observing mode without scanning telescope motion. As a result, we are currently restricted to sources brighter than the atmospheric variations (Mars, Venus, Saturn and Jupiter). However, initial tests confirmed that using the wobbler to modulate the source signal allows focusing on weaker sources, too. This is the only observing mode, so far, for which the use of the wobbler with LABOCA has been tested.

8.2.3 Skydips

The attenuation of the astronomical signals due to the atmospheric opacity is determined with skydips. These scans measure the power of the atmospheric emission as a function of the airmass while tipping the telescope from high to low elevation. A skydip procedure consists of two steps: a hot-sky calibration scan, to provide an absolute measurement of the sky temperature, followed by a continuous tip scan in elevation; see also Sect. 9.5.

9 Performance on the sky and sensitivity

9.1 Number of channels

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=65 65 535 525, clip, angle=-90]{1454fig10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg29.png) |

Figure 10: Footprint of LABOCA on sky, measured with a beam map on the planet Mars. The ellipses represent the FWHM shape of each beam on sky, as given by a two-dimensional Gaussian fit to the single-channel map of each bolometer. Only bolometers with useful signal-to-noise ratios are shown in this map. See also Fig. 12. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

At the time of the commissioning, the number of channels with sky response was 266 (90% of the nominal 295 bolometers). Of these, 6 channels show cross-talk and 12 channels have low sensitivity (less than 10% of the mean responsivity). Two additional bolometers have been blinded by blocking their horn antennas with absorber material so they can be used to monitor the temperature fluctuations of the array. The number of channels used for astronomical observations is therefore 248 (84% yield, see Fig. 10).

9.2 Array parameters

Position on sky and relative gain of each bolometer are derived from

fully sampled maps (hereafter called beam maps) of the planets

Mars and Saturn (see Fig. 10), besides giving a realistic

picture of the optical distortions over the FoV. Variations among

maps were found to be within a few arc seconds for the positions and

below 10% for peak flux densities. A table with average receiver

parameters (RCP)![]() is periodically computed from beam maps and implemented in the BoA software (see Sect. 10).

The accuracy of the relative bolometer positions from this master RCP is

typically below 1'' (5% of the beam size) and the gain accuracy is

better than 5%, confirming the good quality (small distortion over

the entire FoV) of the tertiary optics (see also

Sect. 2).

is periodically computed from beam maps and implemented in the BoA software (see Sect. 10).

The accuracy of the relative bolometer positions from this master RCP is

typically below 1'' (5% of the beam size) and the gain accuracy is

better than 5%, confirming the good quality (small distortion over

the entire FoV) of the tertiary optics (see also

Sect. 2).

9.3 Beam shape

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{1454fig11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg30.png) |

Figure 11:

Radial profile of the LABOCA beam derived by averaging the beams of all 248 functional bolometers

from fully sampled maps on Mars. The error bars show the standard deviation.

The main beam is well described by a Gaussian with a FWHM of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The LABOCA beam shape was derived for individual bolometers from fully

sampled maps on Mars (see Fig. 10) as well as on pointing

scans on Uranus and Neptune. Both methods lead to comparable results

and give an almost circular Gaussian with a FWHM of

(after deconvolution from the source

and pixel sizes). We also investigated the error beam pattern of LABOCA

on beam maps on Mars and Saturn (see Fig. 11). The

beam starts to deviate from a Gaussian at -20 dB (1% of the peak

intensity). The first error beam pattern can be approximated by a

Gaussian with a peak of -18.3 dB and a FWHM of

(after deconvolution from the source

and pixel sizes). We also investigated the error beam pattern of LABOCA

on beam maps on Mars and Saturn (see Fig. 11). The

beam starts to deviate from a Gaussian at -20 dB (1% of the peak

intensity). The first error beam pattern can be approximated by a

Gaussian with a peak of -18.3 dB and a FWHM of

,

the

support legs of the subreflector are visible at the -25 dB (0.3%

level). The fraction of the power in the first error beam is

,

the

support legs of the subreflector are visible at the -25 dB (0.3%

level). The fraction of the power in the first error beam is  18%.

18%.

9.4 Calibration

The astronomical calibration was achieved on Mars, Neptune and Uranus

and a constant conversion factor of  Jy beam-1

Jy beam-1  V-1 was

determined between LABOCA response and flux density. For the determination

of the calibration factor we have used the fluxes of planets determined with

the software ASTRO

V-1 was

determined between LABOCA response and flux density. For the determination

of the calibration factor we have used the fluxes of planets determined with

the software ASTRO![]() .

The overall calibration accuracy for LABOCA is about 10%.

We have also defined a list of secondary calibrators

and calibrated them against the planets (see Appendix A).

In order to improve the absolute flux determination, the calibrators

are observed routinely every

.

The overall calibration accuracy for LABOCA is about 10%.

We have also defined a list of secondary calibrators

and calibrated them against the planets (see Appendix A).

In order to improve the absolute flux determination, the calibrators

are observed routinely every  2 h between observations of

scientific targets.

2 h between observations of

scientific targets.

9.5 Sky opacity determination

Atmospheric absorption in the passband of LABOCA attenuates the astronomical signals as

where the line of sight optical depth

where the line of sight optical depth

can be as high as 1 for observations at low elevation

with 2 mm of precipitable water vapor (PWV), typical limit for observations with LABOCA.

The accuracy of the absolute calibration, therefore, strongly depends on the precision in the determination of

can be as high as 1 for observations at low elevation

with 2 mm of precipitable water vapor (PWV), typical limit for observations with LABOCA.

The accuracy of the absolute calibration, therefore, strongly depends on the precision in the determination of

.

.

We use two independent methods for determining

.

The first one relies on the PWV level measured every minute by the APEX radiometer broadly along the line of sight.

The PWV is converted into

.

The first one relies on the PWV level measured every minute by the APEX radiometer broadly along the line of sight.

The PWV is converted into

using an atmospheric transmission model (ATM, Pardo et al. 2001) and

the passband of LABOCA (see Sect. 4.1). The accuracy of this approach is limited by the knowledge of the passband,

the applicability of the ATM and the accuracy of the radiometer.

using an atmospheric transmission model (ATM, Pardo et al. 2001) and

the passband of LABOCA (see Sect. 4.1). The accuracy of this approach is limited by the knowledge of the passband,

the applicability of the ATM and the accuracy of the radiometer.

The second method uses skydips (see Sect. 8.2.3).

As the telescope moves from high to low elevation,

increases with airmass.

The increasing atmospheric load produces an increasing total power signal converted

to effective sky temperature (

increases with airmass.

The increasing atmospheric load produces an increasing total power signal converted

to effective sky temperature (

)

by direct comparison with a reference hot load.

The dependence of

)

by direct comparison with a reference hot load.

The dependence of

on elevation is then fitted to determine the zenith opacity

on elevation is then fitted to determine the zenith opacity  ,

used as parameter (see, e.g., Chapman et al. 2004).

,

used as parameter (see, e.g., Chapman et al. 2004).

Since LABOCA is installed in the Cassegrain cabin of APEX, when performing skydips the receiver suffers a wide,

continuous rotation (about 70 degrees in 20 s), which affects the stability of the sorption cooler,

thus inducing small variations of the bolometers temperature ( 1-2 mK).

These temperature fluctuations mimic an additional total power signal with amplitude comparable to the atmospheric signal.

The bolometers temperature, however, is monitored with high accuracy by the 3He-stage thermometer (see Sect. 3.3)

and by the two blind bolometers (see Sect. 9.1), making possible a correction of the skydip data.

1-2 mK).

These temperature fluctuations mimic an additional total power signal with amplitude comparable to the atmospheric signal.

The bolometers temperature, however, is monitored with high accuracy by the 3He-stage thermometer (see Sect. 3.3)

and by the two blind bolometers (see Sect. 9.1), making possible a correction of the skydip data.

The values of  resulting from the skydip analysis are robust,

yet up to

resulting from the skydip analysis are robust,

yet up to  30% higher than those obtained from the radiometer.

There are several possible explanation for the discrepancy:

it could be the result of some incorrect assumptions going into the skydip model (e.g. the sky temperature),

or the model itself may be incomplete. The non-linearity of the bolometers can be another factor.

The detector responsivities are expected to change with the optical load as

30% higher than those obtained from the radiometer.

There are several possible explanation for the discrepancy:

it could be the result of some incorrect assumptions going into the skydip model (e.g. the sky temperature),

or the model itself may be incomplete. The non-linearity of the bolometers can be another factor.

The detector responsivities are expected to change with the optical load as

(to first order in

(to first order in  ),

where

),

where  can be related to the bolometer constants (Mather 1984) and the optical configuration.

Combined with the sky response, the bolometer non-linearities would increase the effective skydip

can be related to the bolometer constants (Mather 1984) and the optical configuration.

Combined with the sky response, the bolometer non-linearities would increase the effective skydip  by a factor

by a factor

.

.

Our practical approach to reconciling the results obtained with the two methods has been to use a linear combination

of radiometer and skydip values such that it gives the most consistent calibrator fluxes

at all elevations![]() .

The excellent calibration accuracy of LABOCA (see Appendix A) underscores this approach.

.

The excellent calibration accuracy of LABOCA (see Appendix A) underscores this approach.

9.6 Sensitivity

The noise-weighted mean point-source sensitivity of the array (noise-equivalent flux density, NEFD) determined from on-sky integrations, is 55 mJy s1/2 (sensitivity per channel). This value is achieved only by filtering the low frequencies (hence large scale emission) to reject residual sky-noise. For extended emission, without low frequency filtering, there is a degradation of sensitivity to a mean array sensitivity of 80-100 mJy s1/2 depending on sky stability. However, there are significant variations of the sensitivity across the array (see Fig. 12, top).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, bb=0 -30 698 704, clip]{1454fig...

...graphics[width=8.8cm, bb= 108 57 348 296,clip]{1454fig12bottom.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg40.png) |

Figure 12: Top: effective point source sensitivities (after low frequencies filtering) of all the useful bolometers of LABOCA (color scale in Jy beam-1). The positions were determined from beam maps on Mars, thus providing a realistic picture of the optical distortions over the FoV (see also Fig. 10). Bottom: distribution of the effective point source sensitivities on the LABOCA array (5 mJy s1/2 binning). The total mapping speed of the array is as if the 250 good bolometers were all identical at a level of 54.5 mJy beam-1 s1/2 (thick black line). The median sensitivity is also shown (dotted line). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

For detection experiments of compact sources with known position,

LABOCA can be centered on the most sensitive part of the array rather

than on the geometric center. This results in an improved point source

sensitivity of  40 mJy s1/2 for compact mapping pattern

like spirals.

40 mJy s1/2 for compact mapping pattern

like spirals.

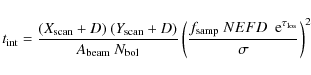

9.7 Mapping speed and time estimate

The relation between the expected residual rms map noise  ,

the surveyed

area on the sky and the integration time can be expressed as

,

the surveyed

area on the sky and the integration time can be expressed as

|

(1) |

where

,

,

are the dimensions of the area covered by

the scanning pattern, D is the size of the array,

are the dimensions of the area covered by

the scanning pattern, D is the size of the array,

is the

area of the LABOCA beam,

is the

area of the LABOCA beam,

is the number of working

bolometers,

is the number of working

bolometers,

is the on source integration time, NEFD is the

average array sensitivity,

is the on source integration time, NEFD is the

average array sensitivity,

is the number of grid points

per beam and

is the number of grid points

per beam and

the line-of-sight opacity.

This formula

the line-of-sight opacity.

This formula

9.8 Noise behavior in deep integrations

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, bb=0 0 351 357, clip]{1454fig13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg49.png) |

Figure 13: Noise behavior for deep integrations has been studied by co-adding about 350 h of blank-field data. The plot shows the effective residual rms noise on sky. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In order to study how the noise averages down with increasing integration time, about 350 h of blank-field mapping observations have been co-added with randomly inverted signs to remove any sources while keeping the noise structure. As shown in Fig. 13, the noise integrates down with t-1/2, as expected.

10 Data reduction

LABOCA data are stored in MB-FITS format (Multi-Beam FITS) by the data writer embedded in APECS. A new software package has been specifically developed to reduce LABOCA data: the Bolometer array data Analysis software (BoA). It is mostly written in the Python language, except for the most computing demanding tasks, which are written in Fortran90.

BoA was first installed and integrated in APECS in early 2006. An extensive description of its functionalities will be given in a separate paper (Schuller et al., in prep.). In this section, we outline the most important features for processing LABOCA data.

10.1 On-line data reduction

During the observations carried out at APEX, the on-line data

calibrator (as part of APECS) performs a quick data reduction of each

scan to provide the observer with a quick preview of the maps or

spectra being observed. This is of particular importance for the

basic pointing and focus observing modes, for which the on-line

calibrator computes and sends back to the observer the pointing

offsets or focus corrections to be applied. For both focus and

pointing scans, only a quick estimate of the correlated noise (see

below) is computed and subtracted from the data. The focus correction

is derived from a parabolic fit to the peak flux measured by the

reference bolometer as a function of the subreflector position. For

pointing scans, the signals of all usable channels are combined into a

map of the central

area, in horizontal coordinates. A

two-dimensional elliptical Gaussian is then fitted to the source in

this map, which gives the pointing offsets, as well as the peak flux

and the dimensions of minor and major axis of the source.

area, in horizontal coordinates. A

two-dimensional elliptical Gaussian is then fitted to the source in

this map, which gives the pointing offsets, as well as the peak flux

and the dimensions of minor and major axis of the source.

10.2 Off-line data reduction

The BoA software can also be used off-line to process any kind of bolometer data acquired at APEX. The off-line BoA runs in the interactive environment of the Python language. In a typical off-line data reduction session, several scans can be combined together, for instance to improve the noise level on deep integrations, or to do mosaicing of maps covering adjacent areas. The result of any data reduction can be stored in a FITS file using standard world coordinate system (WCS) keywords, which can then be read by other softwares for further processing (e.g. source extraction, or overlay with ancillary data).

The common steps involved in the processing of LABOCA data are the following:

- Flux calibration. A correct scaling of the flux involves, at least, two steps: the opacity correction and the counts-to-Jy conversion. The zenith opacity is derived from skydip measurements (see Sects. 8.2.3 and 9.5), and the line of sight opacity also depends on the elevation. The counts-to-Jy factor has been determined during the commissioning of the instrument, but additional correction factors may be applied, depending on the flux measured on calibrators with known fluxes (see Sect. 9.4).

- Flagging of bad

channels. Bolometers not responding or with strong excess noise are

automatically identified from their rms noise being well outside the

main distribution of the rms noise values across the array. They can

be flagged, which means that the signal that they recorded is not used

any further in the processing.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{Old/1454fig14top.eps}\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{1454fig14bottom.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11454-08/Timg51.png)

Figure 14: Time series of a bolometer signal on blank sky at consecutive steps during the data reduction process with BoA. The signals, labeled from 1 to 5, are shown for: 1) original signal on sky; 2) after correcting for system temperature variations using the blind bolometers (

200

200  K during this scan);

3) after median skynoise removal over the full array, one single iteration;

4) after median skynoise removal over the full array, 10 iterations;

5) after correlated noise removal, grouping the channels by amplifier and cable, 5 iterations (shifted to a -3 level, for clarity).

K during this scan);

3) after median skynoise removal over the full array, one single iteration;

4) after median skynoise removal over the full array, 10 iterations;

5) after correlated noise removal, grouping the channels by amplifier and cable, 5 iterations (shifted to a -3 level, for clarity).Open with DEXTER - Flagging of stationary points. The data acquired when the telescope was too slow to produce a signal inside the useful part of the post-detection frequency band of LABOCA (e.g. below 0.1 Hz, see Sect. 8.1 and Fig. 8) can be flagged. Data obtained when the telescope acceleration is very high may show some excess noise, and can also be flagged.