| Issue |

A&A

Volume 497, Number 3, April III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 815 - 825 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811417 | |

| Published online | 18 February 2009 | |

Spectroscopic orbits and variations of RS Ophiuchi

E. Brandi1,2,3 - C. Quiroga1,2 - J. Miko![]() ajewska4 -

O. E. Ferrer1,5 -

L. G. García1,2

ajewska4 -

O. E. Ferrer1,5 -

L. G. García1,2

1 - Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata (UNLP), Argentina

2 -

Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata (CCT La Plata-CONICET-UNLP), Argentina

3 -

Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (CIC), Argentina

4 -

Copernicus Astronomical Center, Warsaw, Poland

5 -

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina

Received 25 November 2008 / Accepted 25 January 2009

Abstract

Aims. The aims of our study are to improve the orbital elements of the giant and to derive the spectroscopic orbit for the white dwarf companion of the symbiotic system RS Oph. Spectral variations related to the 2006 outburst are also studied.

Methods. We performed an analysis of about seventy optical and near infrared spectra of RS Oph that were acquired between 1998 and June 2008. The spectroscopic orbits were obtained by measuring the radial velocities of the cool component absorption lines and the broad H emission wings, which seem to be associated with the hot component. A set of cF-type absorption lines were also analyzed for a possible connection with the hot component motion.

emission wings, which seem to be associated with the hot component. A set of cF-type absorption lines were also analyzed for a possible connection with the hot component motion.

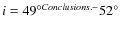

Results. A new period of 453.6 days and a mass ratio,

![]() were determined. Assuming a massive white dwarf as the hot component (

were determined. Assuming a massive white dwarf as the hot component (

![]() )

the red giant mass is

)

the red giant mass is

![]() and the orbit inclination,

and the orbit inclination,

.

The cF-type lines are not associated with either binary component, and are most likely formed in the material streaming towards the hot component. We also confirm the presence of the Li I doublet in RS Oph and its radial velocities fit very well to the M-giant radial velocity curve. Regardless of the mechanism involved to produce lithium, its origin is most likely from within the cool giant rather than material captured by the giant at the time of the nova explosion.

.

The cF-type lines are not associated with either binary component, and are most likely formed in the material streaming towards the hot component. We also confirm the presence of the Li I doublet in RS Oph and its radial velocities fit very well to the M-giant radial velocity curve. Regardless of the mechanism involved to produce lithium, its origin is most likely from within the cool giant rather than material captured by the giant at the time of the nova explosion.

The quiescent spectra reveal a correlation of the H I and He I emission line fluxes with the monochromatic magnitudes at 4800 Å, indicating that the hot component activity is responsible for those flux variations. We also discuss the spectral characteristics around 54-55 and 240 days after the 2006 outburst. In April 2006 most of the emission lines present a broad pedestal with a strong and narrow component at about -20 km s-1 and two other extended emission components at -200 and +150 km s-1. These components could originate in a bipolar gas outflow supporting the model of a bipolar shock-heated shell expanding through the cool component wind perpendicularly to the binary orbital plane. Our observations also indicate that the cF absorption system was disrupted during the outburst, and restored about 240 days after the outburst, which is consistent with the resumption of accretion.

Key words: stars: binaries: symbiotic - stars: novae, cataclysmic variables - stars: individual: RS Oph - techniques: spectroscopic

1 Introduction

RS Oph is a recurrent symbiotic nova in which a white dwarf near the Chandrasekhar limit orbits inside the outer wind of a red giant. The system has had numerous recorded outbursts (1898, 1933, 1958, 1967, 1985). The most recent outburst began on 2006 February 12 and multifrequency observations confirmed the current model for the outburst in which the massive white dwarf accretes material from the red giant until a thermonuclear runaway ensues and high velocity gas is ejected from the white dwarf. Because the white dwarf is orbiting inside the outer layers/wind of the red giant, a strong shock structure is established around the system.

For RS Oph, Garcia (1986) made the first orbital period estimate of about 230 days, based on eight radial velocity measurements. Two sets of lines were considered: M star absorption features and absorption cores of Fe II emission lines due to a shell. He could not, however, derive the mass ratio. Oppenheimer & Mattei (1993) analysed intervals between outbursts in the AAVSO visual light curve and found the strongest periods ranged between 892 and 2283 days. Dobrzycka & Kenyon (1994, hereafter DK94) continued monitoring the radial velocities of RS Oph during quiescence. They also separated their echelle spectra into sets of M-type and A-type absorption lines, both of which resulted in a period of 460 days. The A-type radial velocity curve was shifted by 0.37 relative to the M giant solution and it was not associated with the hot component motion. They concluded that their results are more reasonable if they only considered the circular orbit of the cool giant. DK94 searched for periodic variations in photometric data of RS Oph collected during 1971-1983 and after the 1985 outburst. For both time intervals they found the light curve to be the superposition of a longer period variation (P=2178 days) and a shorter variation (P=508 days). The longer period was in agreement with P=2283 days given by Oppenheimer & Mattei (1993) but it did not appear in their radial velocity analysis so it could not be associated with the orbital motion. Fifteen infrared radial velocities were used by Fekel et al. (2000, hereafter FJHS00) combined with the 47 optical velocities of DK94 in order to improve the orbital elements of the giant. FJHS00 fitted a new period of 455.72 days for a circular solution and eccentric orbits were rejected applying the test of Lucy & Sweeney (1971).

In this study, we have collected spectroscopic data of RS Oph from September 1998 until October 2006 and two Feros spectra taken on May and June 2008 were also included in our analysis. Our observation closest to the eruption was obtained in April 2006.

We describe our observations in Sect. 2; in Sect. 3 we determine double-line spectroscopic orbits for RS Oph; in Sect. 4 spectral characteristics observed during quiescence are presented; in Sect. 5 we describe spectral changes during the active phase at 54-55 and 240 days after eruption and finally a brief discussion of our results and conclusions are given in Sect. 6.

2 Observations

2.1 Spectroscopy

Spectroscopic observations of RS Oph were performed with the 2.15 m ``Jorge Sahade''

telescope of CASLEO![]() (San Juan, Argentina), during 1998-2006. 65 spectra with

resolution 12 000-15 000 were obtained with a REOSC echelle spectrograph using a Tek CCD

(San Juan, Argentina), during 1998-2006. 65 spectra with

resolution 12 000-15 000 were obtained with a REOSC echelle spectrograph using a Tek CCD

pixels.

The CCD data were reduced with IRAF

pixels.

The CCD data were reduced with IRAF![]() packages CCDRED and ECHELLE and all the spectra were

measured using the SPLOT task within IRAF.

packages CCDRED and ECHELLE and all the spectra were

measured using the SPLOT task within IRAF.

To obtain the flux calibration, standard stars from Hamuy et al. (1992) and Hamuy et al. (1994) were observed each night. A comparison of the spectra of the standards suggests that the flux calibration errors are about 20% in the central part of each echelle order.

Two high resolution spectra were acquired in May and June 2008 with

the Feros spectrograph mounted at the 2.2 m telescope at ESO, La Silla (Chile).

An EEV CCD-44 with

pixels was used as the detector with a pixel size of

pixels was used as the detector with a pixel size of

m and resolving power of R=60 000.

m and resolving power of R=60 000.

3 Spectroscopic orbits

Spectroscopic orbits of RS Oph were calculated using high resolution spectra collected at CASLEO during the period 1998-2006.

Table 1:

Radial velocities of the M-giant component, H -wings and cF-absorptions in RS Oph.

-wings and cF-absorptions in RS Oph.

To obtain the radial velocities of the red giant we have measured

M-type absorptions in the region

-8000 Å, corresponding to

Fe I, Ti I, Ni I, Si I, O I, Zr I,

Co I, V I, Mg I and Gd II.

We have also identified and measured absorption lines of singly ionized elements in the blue region of our spectra (

-8000 Å, corresponding to

Fe I, Ti I, Ni I, Si I, O I, Zr I,

Co I, V I, Mg I and Gd II.

We have also identified and measured absorption lines of singly ionized elements in the blue region of our spectra (

-5800 Å), which resemble spectra of A-F supergiants. This set of absorption lines, called cF-absorptions, are believed to be linked to the hot companion (e.g. Miko

-5800 Å), which resemble spectra of A-F supergiants. This set of absorption lines, called cF-absorptions, are believed to be linked to the hot companion (e.g. Miko![]() ajewska & Kenyon 1992; Quiroga et al. 2002; Brandi et al. 2005). These are basically the same lines that are called A-type absorption lines

by DK94. As the Fe II lines show very variable and complex profiles with emission components, only the stronger Ti II absorption lines were considered in our orbital solutions.

ajewska & Kenyon 1992; Quiroga et al. 2002; Brandi et al. 2005). These are basically the same lines that are called A-type absorption lines

by DK94. As the Fe II lines show very variable and complex profiles with emission components, only the stronger Ti II absorption lines were considered in our orbital solutions.

In both cases individual radial velocities were obtained by a Gaussian fit of the line profiles. A mean value was calculated for each spectrum and the resulting heliocentric velocities together with their standard errors and with the number of measured lines are given in Table 1. The published radial velocities of the M-giant were also included in the table.

Table 2: Orbital solutions of RS Oph.

Table 2 lists the resulting orbital solutions for the M-giant using only our radial velocities as well as our radial velocities combined with the DK94 and FJHS00 data and considering in this case weighted values of radial velocities. We have applied a weight of 1 to the FJHS00 data and weights 0.33, 0.67 and 1 when the errors are larger than 4, between 2 and 3 and less than 2, respectively, for both the DK94 and our data. But we noted that the weighted solutions show no important differences when a weight of 1 is applied to all the data.

A new orbital period of

days was determined. An elliptical orbit

(

days was determined. An elliptical orbit

(

)

fits the measured velocities slightly better than a

circular one (see Fig. 1a).

)

fits the measured velocities slightly better than a

circular one (see Fig. 1a).

We have also determined the radial velocities from the broad emission wings of

H which should reflect the motion of the hot component if the wings were formed in

the inner region of the accretion disk or in an extended envelope near the hot component.

For this we have used the method outlined by Schneider & Young (1980, for more details see Quiroga et al. 2002). This method consists of convolving the data with two identical Gaussian bandpasses whose centers have a separation of 2b with standard deviation

which should reflect the motion of the hot component if the wings were formed in

the inner region of the accretion disk or in an extended envelope near the hot component.

For this we have used the method outlined by Schneider & Young (1980, for more details see Quiroga et al. 2002). This method consists of convolving the data with two identical Gaussian bandpasses whose centers have a separation of 2b with standard deviation  .

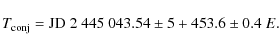

We have experimented with a range of values for b and

.

We have experimented with a range of values for b and  fixed at 3 Å, for which we have obtained the circular orbit solutions. Figure 2 shows the dependence of the standard error

fixed at 3 Å, for which we have obtained the circular orbit solutions. Figure 2 shows the dependence of the standard error  of the orbital semi-amplitude K, and the

of the orbital semi-amplitude K, and the

ratio, as a function of b. It is noticeable that

ratio, as a function of b. It is noticeable that  and

and

increases sharply for b larger than

increases sharply for b larger than  7 Å. We can attribute these large standard errors to the velocity measurements dominated by the noise in the continuum rather than by the extreme high velocity wings of the line profile. We have therefore adopted

7 Å. We can attribute these large standard errors to the velocity measurements dominated by the noise in the continuum rather than by the extreme high velocity wings of the line profile. We have therefore adopted  as the best value. The heliocentric radial velocities of the broad emission wings of H

as the best value. The heliocentric radial velocities of the broad emission wings of H are included in Table 1.

are included in Table 1.

The broad emission line wings of H show a mean velocity similar to the red giant

systemic velocity (see Fig. 1b). They are clearly in antiphase with the

M-giant curve, which suggests that they are really formed in a region very near to the hot component.

show a mean velocity similar to the red giant

systemic velocity (see Fig. 1b). They are clearly in antiphase with the

M-giant curve, which suggests that they are really formed in a region very near to the hot component.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=11cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg41.png) |

Figure 1:

Radial velocity curves and orbital solutions

for RS Oph. The data are phased with a period of 453.6 days and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Finally we have calculated the combined orbital solutions from the M-giant absorptions

and from the H broad emission wings (see Table 2). From a comparison of the variances of the velocities of the two individual solutions,

weights of 0.64 and 1 were given to the H

broad emission wings (see Table 2). From a comparison of the variances of the velocities of the two individual solutions,

weights of 0.64 and 1 were given to the H wings and the M-giant velocities, respectively.

Leaving the period as a free parameter and taking a circular orbit, the best solution

corresponds to a similar period of

wings and the M-giant velocities, respectively.

Leaving the period as a free parameter and taking a circular orbit, the best solution

corresponds to a similar period of

days

and adopting the period 453.6 days, the best combined solution leads to a lower

eccentricity,

days

and adopting the period 453.6 days, the best combined solution leads to a lower

eccentricity,

.

Moreover, we have considered binned data of radial velocities taking phase intervals of 0.05, and as it is shown in Table 2, very similar

results were obtained. These solutions show clear antiphase variations of both sets of radial velocities and the systemic velocity agrees very well with that of the cool component orbital

solutions. The combined unbinned and binned solutions are shown in Figs. 1c and d,

respectively.

.

Moreover, we have considered binned data of radial velocities taking phase intervals of 0.05, and as it is shown in Table 2, very similar

results were obtained. These solutions show clear antiphase variations of both sets of radial velocities and the systemic velocity agrees very well with that of the cool component orbital

solutions. The combined unbinned and binned solutions are shown in Figs. 1c and d,

respectively.

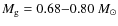

Using the combined circular solutions for unbinned data, we have estimated the mass ratio

![]() ,

the component masses

,

the component masses

![]() and

and

![]() ,

and the binary separation

,

and the binary separation

.

Assuming that the hot component is a massive white dwarf close to the Chandrasekhar

limit (

.

Assuming that the hot component is a massive white dwarf close to the Chandrasekhar

limit (

-

-

), we estimate the red giant mass,

), we estimate the red giant mass,

-

-

and the orbit inclination,

and the orbit inclination,

-

-

,

which is consistent with the absence of eclipses

in both, the optical light curve and the H I and He I emission line

fluxes in our spectra.

,

which is consistent with the absence of eclipses

in both, the optical light curve and the H I and He I emission line

fluxes in our spectra.

A lower limit for the mass ratio can be also derived from the ratio of the rotational

velocity to the orbital semiamplitude of the red giant and assuming that the giant is

synchronized.

Adopting

![]() (Zamanov et al. 2007) and

(Zamanov et al. 2007) and

![]() (Table 2) results in

(Table 2) results in

![]() .

This lower limit

is surprisingly close to the mass ratio derived from the radial velocity curves, and

indicates that either the giant is filling its Roche lobe (RL) - the actual q should then be

equal to

.

This lower limit

is surprisingly close to the mass ratio derived from the radial velocity curves, and

indicates that either the giant is filling its Roche lobe (RL) - the actual q should then be

equal to

- or that its measured rotational

velocity is faster than the synchronized value. The first possibility is favored by

theoretically predicted synchronization and circularization time-scales for convective

stars (Zahn 1977).

It is also easier to ensure the high mass tranfer and accretion rate required by the

activity and short nova outburst recurrence time of RS Oph. On the other hand,

the presence of an RL-filling giant implies that the distance to RS Oph is a factor of 2 larger than generally accepted based on observational evidence (Barry et al. 2008).

- or that its measured rotational

velocity is faster than the synchronized value. The first possibility is favored by

theoretically predicted synchronization and circularization time-scales for convective

stars (Zahn 1977).

It is also easier to ensure the high mass tranfer and accretion rate required by the

activity and short nova outburst recurrence time of RS Oph. On the other hand,

the presence of an RL-filling giant implies that the distance to RS Oph is a factor of 2 larger than generally accepted based on observational evidence (Barry et al. 2008).

The cF absorption lines do not trace clearly the orbit of the hot component. Any orbital

solution leads to a significant eccentricity (see Table 2) and the radial

velocity curve is shifted by  -0.26 P (0.74 P) relative to the M giant solution

instead of 0.5 P (see Fig. 3). We think, in agreement with DK94, that in

RS Oph the cF absorption lines are not associated with either binary component, and are most

likely formed in the material streaming towards the hot component. We note here that

similar complications with the blue absorption system occurred for a few other active symbiotic systems. Miko

-0.26 P (0.74 P) relative to the M giant solution

instead of 0.5 P (see Fig. 3). We think, in agreement with DK94, that in

RS Oph the cF absorption lines are not associated with either binary component, and are most

likely formed in the material streaming towards the hot component. We note here that

similar complications with the blue absorption system occurred for a few other active symbiotic systems. Miko![]() ajewska & Kenyon (1996) failed to derive any radial velocity curve and orbital

solution for the blue absorption system in Z And. In CI Cyg the radial velocities of the

F-type absorption system suggest that their formation region is the material streaming

from the giant near the hot component (Miko

ajewska & Kenyon (1996) failed to derive any radial velocity curve and orbital

solution for the blue absorption system in Z And. In CI Cyg the radial velocities of the

F-type absorption system suggest that their formation region is the material streaming

from the giant near the hot component (Miko![]() ajewska & Miko

ajewska & Miko![]() ajewski 1988), whereas a possible

correlation between AR Pav's activity and the departures of the cF absorption velocities

from the circular orbit suggests that this absorption system also may be affected by

material streaming towards the hot component, presumably in a region where the stream

encounters an accretion disk or an extended envelope around the hot component

(Quiroga et al. 2002). We can see in Fig. 3 the departures

of the cF-abs radial velocities from the circular orbit of the hot component due to a

significant contribution from the stream.

ajewski 1988), whereas a possible

correlation between AR Pav's activity and the departures of the cF absorption velocities

from the circular orbit suggests that this absorption system also may be affected by

material streaming towards the hot component, presumably in a region where the stream

encounters an accretion disk or an extended envelope around the hot component

(Quiroga et al. 2002). We can see in Fig. 3 the departures

of the cF-abs radial velocities from the circular orbit of the hot component due to a

significant contribution from the stream.

In Figs. 1 and 3 and hereafter we adopt the period of 453.6 days and the origin of the phases corresponds to the inferior conjunction of the

M-giant:

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG2.eps}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg58.png) |

Figure 2:

The standard error of the orbital semi-amplitude |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.05cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg59.png) |

Figure 3:

Phased radial velocities of the cF-absorption lines (dots) and the best circular solution (solid line) for the hot component based on the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 RS Oph at quiescence

Fluctuations in the fluxes of the emission lines and the

continuum are observed during the period of quiescence

covered by our observations. Several authors have previously reported such behaviour

of RS Oph, outside the eruptive episodes (see Anupama & Miko![]() ajewska 1999,

and refences therein).

ajewska 1999,

and refences therein).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,angle=90,clip]{Brandi_FIG4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg60.png) |

Figure 4:

Panels a) and b): profiles of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3:

Mean values of radial velocities and equivalent widths of the central

absorptions in H and H

and H .

.

The spectra present essentially emission lines of H I, He I and

[O I] at 6300 Å. In the observed members of the Balmer series, the broad emission is cut by a central

absorption with a red peak always stronger than the blue one.

Figure 4, left and central panels, show H profiles for

several epochs. At quiescence the central absorption remains present although with

variable intensity over the

whole orbital cycle, whereas it disappears during the eruption, and it is weakly

visible again in October 2006. The radial velocity of the central absorption of H

profiles for

several epochs. At quiescence the central absorption remains present although with

variable intensity over the

whole orbital cycle, whereas it disappears during the eruption, and it is weakly

visible again in October 2006. The radial velocity of the central absorption of H varies between -60 and -40

varies between -60 and -40

.

As it is shown in Fig. 5a

this variation does not follow the motion of any stellar component of the system but

Figs. 5b and c

show changes of both the radial velocities and the equivalent widths with the different

cycles of the binary, in the sense that the mean velocity

was increasing until cycle 16 (May 2003) and then decreasing, whereas the equivalent widths

were monotonically increasing.

.

As it is shown in Fig. 5a

this variation does not follow the motion of any stellar component of the system but

Figs. 5b and c

show changes of both the radial velocities and the equivalent widths with the different

cycles of the binary, in the sense that the mean velocity

was increasing until cycle 16 (May 2003) and then decreasing, whereas the equivalent widths

were monotonically increasing.

The profile of H also presents a double peak structure but the radial velocity of

the central absorption is rather constant, without a clear variation with

orbital phase or orbital cycle (see Figs. 5d-f).

also presents a double peak structure but the radial velocity of

the central absorption is rather constant, without a clear variation with

orbital phase or orbital cycle (see Figs. 5d-f).

Significant changes in the radial velocity of the central absorption in both

H and H

and H were observed in the higher resolution Feros spectra

between May and June 2008 (asterisks in Fig. 5). An explanation of this behaviour correlating the radial velocities with the flickering activity and the accretion processes in RS Oph is in progress.

were observed in the higher resolution Feros spectra

between May and June 2008 (asterisks in Fig. 5). An explanation of this behaviour correlating the radial velocities with the flickering activity and the accretion processes in RS Oph is in progress.

Broad emission components were detected in the emission line He I

5875 during April 2004 and September 2005 (see Fig. 4, right panel)

at velocities of the order of

5875 during April 2004 and September 2005 (see Fig. 4, right panel)

at velocities of the order of

.

The intensity of the He I emission lines and the presence of these broad components

change quickly with a time scale of one or two days.

.

The intensity of the He I emission lines and the presence of these broad components

change quickly with a time scale of one or two days.

Figure 6 presents the H fluxes against the m4800 magnitudes calculated

from our spectra. The figure shows that a clear correlation between both data exists,

confirming that the emission line variability is correlated with the hot component

activity (Anupama & Miko

fluxes against the m4800 magnitudes calculated

from our spectra. The figure shows that a clear correlation between both data exists,

confirming that the emission line variability is correlated with the hot component

activity (Anupama & Miko![]() ajewska 1999).

ajewska 1999).

4.1 Presence of the Li I  6707 absorption line

6707 absorption line

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG5a.eps} \includegraphics[width=5cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG5b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg62.png) |

Figure 5:

Radial velocities and equivalent widths of the central absorptions of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg63.png) |

Figure 6:

Correlation of the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

One unsolved problem in astrophysics is the origin of lithium and other light elements in the universe. How and when lithium is depleted and an understanding of the processes controlling lithium production are still not completely resolved. The synthesis of 7Li in explosive hydrogen burning, in particular in accreting (CO or ONe) white dwarfs exploding as classical novae has been studied by several authors (see Jordi 2005, and references therein) and novae are predicted to be important sources of Galactic lithium.

However the observation of 7Li in the ejecta of a nova outburst has

been rather elusive.

The Li I

line has been detected in the recurrent

symbiotic novae T CrB (Shabhaz et al. 1999) and RS Oph (Wallerstein et al. 2006).

Wallerstein et al.(2008) have recently derived Li abundances in these stars,

line has been detected in the recurrent

symbiotic novae T CrB (Shabhaz et al. 1999) and RS Oph (Wallerstein et al. 2006).

Wallerstein et al.(2008) have recently derived Li abundances in these stars,

for RS Oph and 0.8 for T CrB, which are close to being solar.

These Li abundances are however significantly higher than those determined for

most single K and M giants.

Such high Li abundances are common in late-type secondaries in neutron

and black hole binaries (e.g. Martin et al. 1994) but extremely rare in the

symbiotic giants. In fact, the Li enhancement

is thus far detected only in the symbiotic Mira V407 Cyg, where it

can probably be explained as a consequence of hot bottom burning, which

occurs in stars with initial masses in the range 4-6

for RS Oph and 0.8 for T CrB, which are close to being solar.

These Li abundances are however significantly higher than those determined for

most single K and M giants.

Such high Li abundances are common in late-type secondaries in neutron

and black hole binaries (e.g. Martin et al. 1994) but extremely rare in the

symbiotic giants. In fact, the Li enhancement

is thus far detected only in the symbiotic Mira V407 Cyg, where it

can probably be explained as a consequence of hot bottom burning, which

occurs in stars with initial masses in the range 4-6

(Tatarnikova et al. 2003). Such an explanation is, however, unlikely in the

case of low mass,

(Tatarnikova et al. 2003). Such an explanation is, however, unlikely in the

case of low mass,

,

nonpulsating giants in RS Oph and T CrB.

,

nonpulsating giants in RS Oph and T CrB.

Our spectra of RS Oph show the presence of the Li I line, and

the radial velocities of this line fit very well to the M-giant radial velocity curve (see right panel Fig. 7).

The identification of the weak and narrow absorption line at 6706-6708 Å with

Li I  6708 is unambiguous since no other neutral element

following the giant motion has a strong transition at that wavelength.

In addition, the presence of this line is clearly seen in the higher resolution

Feros spectra. The feature was observed in all our spectra, except in April 2006 where all the

absorption lines were overwhelmed by very strong blue continuum from the nova outburst.

6708 is unambiguous since no other neutral element

following the giant motion has a strong transition at that wavelength.

In addition, the presence of this line is clearly seen in the higher resolution

Feros spectra. The feature was observed in all our spectra, except in April 2006 where all the

absorption lines were overwhelmed by very strong blue continuum from the nova outburst.

This result indicates that, regardless of the mechanism involved to generate lithium, it should operate within the cool giant atmosphere. The observed Li would be the initial Li (which is observed in non convective stars) if some process operating in such binary systems as RS Oph and T CrB, e.g. delayed onset of convection or a lack of differential rotation due to tidal locking, can inhibit lithium depletion (Shabhaz et al. 1999).

Wallerstein et al. (2008) offered another

possibility for the presence of Li. They suggested that it is freshly

created in the interior and convected to the surface. They also noted that some G and K-type

giants have very high atmospheric Li abundances. In the case of these Li-rich giants,

Charbonnel & Balachandran (2000) identified two distinct episodes of Li production occuring in advanced evolutionary phases depending upon the mass of the star. Low-mass RGB stars which later undergo a helium flash produce Li at the start of the red giant luminosity bump phase whereas in intermediate-mass stars the Li-rich phase occurs when the convective envelope deepens at the base of the AGB. The position of the cool giant of T CrB in the HR diagram is consistent with a low-mass,

,

star at the top of the RGB whereas the location of RS Oph is consistent with such a giant only if its metallicity is significantly subsolar (Miko

,

star at the top of the RGB whereas the location of RS Oph is consistent with such a giant only if its metallicity is significantly subsolar (Miko![]() ajewska 2008), and in both cases the stars are located far from the RGB bump. On the other hand, Wallerstein et al. (2008) found a normal, nearly solar, ratio of metals to hydrogen in both RS Oph and T CrB, and they concluded that the giant component has not yet lost sufficient mass to make its atmosphere deficient in hydrogen. It seems therefore unlikely that the initial mass of the M giant was significantly greater than its current estimate of

ajewska 2008), and in both cases the stars are located far from the RGB bump. On the other hand, Wallerstein et al. (2008) found a normal, nearly solar, ratio of metals to hydrogen in both RS Oph and T CrB, and they concluded that the giant component has not yet lost sufficient mass to make its atmosphere deficient in hydrogen. It seems therefore unlikely that the initial mass of the M giant was significantly greater than its current estimate of

.

.

An alternative explanation is the pollution of the giant by the nova ejecta.

This explanation has,

however, some weak points. In particular, the red giant should very efficiently

accrete the Li-rich

material ejected at very high velocity (a few 1000

!) to be significantly polluted.

Moreover there is also serious controversy about the production of Li during such an

explosion.

!) to be significantly polluted.

Moreover there is also serious controversy about the production of Li during such an

explosion.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg71.png) |

Figure 7:

( Left) Presence of the Li I |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 RS Oph in 2006

High-dispersion spectra of RS Oph were taken at CASLEO with the same

instrumental configuration on 2006 April 7-8 and October 12, that is, 54-55

and 240 days following the explosion.

The spectra of April show broad emission lines of hydrogen recombination

lines, together with He I, He II, Fe II, N III,

[O I]  6300, [O III]

6300, [O III]  5007,

[N II]

5007,

[N II]  5754 and the Raman band at

5754 and the Raman band at  6825 Å.

The cF absorption system is not observed in April 2006.

Very narrow emission components are seen on top of the broad

emission components.

6825 Å.

The cF absorption system is not observed in April 2006.

Very narrow emission components are seen on top of the broad

emission components.

Strong coronal emission lines such as [Fe XIV]  5305,

[A X]

5305,

[A X]  5535 and [Fe X]

5535 and [Fe X]  6375

(Fig. 8) are also present, showing the same structure in the profiles.

Our measures of the integrated fluxes, the radial velocity of the emission line

components and the full width at zero intensity (FWZI) of several stronger lines

are shown in Table 4.

6375

(Fig. 8) are also present, showing the same structure in the profiles.

Our measures of the integrated fluxes, the radial velocity of the emission line

components and the full width at zero intensity (FWZI) of several stronger lines

are shown in Table 4.

Most of the emission lines present a strong and narrow component with a

radial velocity between -14 and -25

and two other components

extended to the blue and the red side.

In the cases of the [N II] and [O III] emission lines and

the coronal lines, the radial velocity of the narrow component is more

negative (-40 and -50

and two other components

extended to the blue and the red side.

In the cases of the [N II] and [O III] emission lines and

the coronal lines, the radial velocity of the narrow component is more

negative (-40 and -50

).

).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg72.png) |

Figure 8: Observed coronal lines in RS Oph on April 2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg73.png) |

Figure 9:

The He I and He II profiles showing a broad pedestal with the

strong narrow component at -15 and -23

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We can see in Fig. 9 the He I

5875, 7065 and

He II

5875, 7065 and

He II  4686, 5411 profiles showing a broad pedestal with

the strong narrow component at -15 and -23

4686, 5411 profiles showing a broad pedestal with

the strong narrow component at -15 and -23

respectively. Two separate

emission components of higher radial velocity are observed at

respectively. Two separate

emission components of higher radial velocity are observed at  -200 and +150

-200 and +150

with the blue component stronger than the red one.

An explanation based on a bipolar gas outflow may be applicable to the presence of these

components with expanding and receding radial velocities.

with the blue component stronger than the red one.

An explanation based on a bipolar gas outflow may be applicable to the presence of these

components with expanding and receding radial velocities.

Table 4: Emission lines of RS Oph on April 2006.

On October 2006, the RS Oph spectrum is slowly restoring its quiescent characteristics.

The cF-absorption system, absent in April 2006, has reappeared.

The intensity of the emission lines decreases, the coronal lines are not observed

and the blue and red components of the He I lines have disappeared. H has

recovered its pre-outburst profile, in particular the emission wings are narrower than in

April 2006 and the emission is cut by an incipient central absorption (see Fig. 4).

A very weak He II

has

recovered its pre-outburst profile, in particular the emission wings are narrower than in

April 2006 and the emission is cut by an incipient central absorption (see Fig. 4).

A very weak He II  4686 line is still observed, although its flux has

decreased by a factor of

4686 line is still observed, although its flux has

decreased by a factor of  90 with respect to that of April 2006. This profile

preserves the strong emission component at

90 with respect to that of April 2006. This profile

preserves the strong emission component at

and two expanding

components at -214 and +192

and two expanding

components at -214 and +192

,

with the red component being stronger

than the blue one, that is, in the opposite sense of that of April (Fig. 10,

left panel).

,

with the red component being stronger

than the blue one, that is, in the opposite sense of that of April (Fig. 10,

left panel).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg78.png) |

Figure 10:

Left panel: N III emission lines observed in

April 2006. The He II |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Conclusions

- 1.

- We have re-determined the spectroscopic orbits of RS Oph based on the radial

velocity curve of the M-type absorption lines at wavelengths longer than 6000 Å.

As the H I broad emission wings seem to follow the hot component motion,

combined orbital solutions for

both components were also determined with a period of 453.6 days, very similar to

those given by FJHS00.

We conclude, as DK94 do, that the cF-type absorption lines are not associated with

either binary component, and are most likely formed in the material streaming

towards the hot component.

Assuming a massive white dwarf as the hot component of the system (

)

the red giant mass results in

)

the red giant mass results in

and the orbit inclination,

and the orbit inclination,

.

.

- 2.

- During the quiescent period of our observations the spectra of RS Oph show

variability in the fluxes of the emission lines and in the continuum. A correlation

of the H I and He I emission line fluxes with the monochromatic

magnitudes at 4800 Å was obtained, indicating

that the hot component activity is responsible for those flux variations.

- 3.

- Our spectra of RS Oph reveal the presence of the Li I 6708 line,

and the radial velocities of this line fit the M-giant radial velocity

curve very well. This result indicates that, whatever the mechanism involved to

generate lithium

would be, it should operate within the cool giant atmosphere.

An alternative explanation is the pollution of the giant by the nova ejecta

but the red giant in this case should very efficiently accrete the Li-rich

material ejected at very high velocity to be significantly polluted.

- 4.

- We present the characteristics of the spectra around 54-55 and 240 days after

the outburst of February 2006. On April 2006 most of the emission lines present

a broad pedestal with a strong and narrow component at about -20

and two

other extended emission components at -200 and +150 km s-1. These components

could originate in a bipolar gas outflow supporting

the model of a bipolar shock-heated shell expanding through the cool component wind and

perpendicular to the orbital plane of the binary.

and two

other extended emission components at -200 and +150 km s-1. These components

could originate in a bipolar gas outflow supporting

the model of a bipolar shock-heated shell expanding through the cool component wind and

perpendicular to the orbital plane of the binary.

- 5.

- Our observations indicate that the cF system was disrupted during the outburst. The cF absorption lines were not observed in our spectra in April 2006 and Zamanov et al. (2006) reported the absence of flickering in June 2006, then the accretion was not yet resumed immediately after the outburst. Both the cF system and the flickering (Worters et al. 2007) were observed again about 240 days after the outburst, which is consistent with the resumption of accretion in RS Oph.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to Drs. N. Morrell and R. Barbá for obtaining the Feros spectrograms at ESO, La Silla (Chile). We also thank the anonymous referee for very valuable comments. This research was partlysupported by Polish research grants Nos. 1P03D01727, and N203 395534. The CCD and data acquisition system at CASLEO has been partly finance by R. M. Rich through US NSF grant AST-90-15827.

References

- Anupama, G. C., & Mikoajewska, J. 1999, A&A ,344, 177 (In the text)

- Barry, R. K., Mukai, K., Sokoloski, J., et al. 2008, in the Proceedings of the Meeting, RS Ophiuchi (2006), ed. N. Evans, M. Bode, & Tim O'Brien, ASP Conf. Ser., 401 (In the text)

- Brandi, E., Mikoajewska, J., Quiroga, C., et al. 2005, A&A, 440, 239 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Charbonnel, C., & Balachandran, S. C. 2000, A&A, 359, 563 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Dobrzycka, D., & Kenyon, S. 1994, AJ, 108, 2259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fekel, F. C., Joyce, R. R., Hinkle, K., & Skrutskie, M. F. 2000, AJ, 119, 1375 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Garcia, M. 1986, AJ, 91, 1400 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hamuy, M., Walker, A. R., Suntzeff, N. B., et al. 1992, PASP, 104, 533 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hamuy, M., Suntzeff, N. B., Heathcote, S. R., et al. 1994, PASP, 106, 566 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Jordi, J. 2005, NuPhA, Nucl. Phys. A, 758, 713

- Lucy, L. B., & Sweeney, M. A. 1971, AJ, 76, 544 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Martin, E. L., Rebolo, R., Casares, J., & Charles, P. A. 1994, ApJ, 435, 791 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mikoajewska, J. 2008, in the Proceedings of the Meeting: RS Ophiuchi (2006), ed. N. Evans, M. Bode, & Tim O'Brien, ASP Conf. Ser., 401 (In the text)

- Mikoajewska, J., & Kenyon, S. J. 1992, AJ, 103, 579 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mikoajewska, J., & Kenyon, S. J. 1996, AJ, 112, 1659 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mikoajewska, J., & Mikoajewski, M. 1988, in The Symbiotic Phenomenon, ed. J. Mikoajewska, M. Friedjung, S. J. Kenyon, & R. Viotti (Dordrecht: Kluwer), 187 (In the text)

- Oppenheimer, B., & Mattei, J. A. 1993, BAAS, 25, 1378 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Quiroga, C., Mikoajewska, J., Brandi, E., et al. 2002, A&A, 387, 139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Schneider, D. P., & Young, P. 1980, ApJ, 238, 946 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Shabhaz, T., Hauschildt, P., Naylor, T., & Ringwald, F. 1999, MNRAS, 306, 675 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Tatarnikova, A. A., Marese, P. M., Munari, U., et al. 2003, MNRAS 344, 1233 (In the text)

- Wallerstein, G., Harrison, T., & Munari, U. 2006, BAAS, 38, 1160 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Wallerstein, G., Harrison, T., Munari, U., & Vanture, A. 2008, PASP, 120, 492 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Worters, H. L., Eyres, S. P. S., Bromage, G. E., & Osborne, J. P. 2007, MNRAS, 379, 1557 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Zahn, J.-P. 1977, A&A, 57, 383 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Zamanov, R., Panov, K., Boer, M., & Coroller, H., Le 2006, The Astronomer's Telegram, 832 (In the text)

- Zamanov, R. K., Bode, M. F., Melo, C. H. F., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 380, 1053 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ... CASLEO

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito operated under agreement between the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la República Argentina and the National Universities of La Plata, Córdoba and San Juan.

- ... IRAF

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatories, which is operated by the association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, INC under contract to the National Science Foundation.

All Tables

Table 1:

Radial velocities of the M-giant component, H![]() -wings and cF-absorptions in RS Oph.

-wings and cF-absorptions in RS Oph.

Table 2: Orbital solutions of RS Oph.

Table 3:

Mean values of radial velocities and equivalent widths of the central

absorptions in H![]() and H

and H![]() .

.

Table 4: Emission lines of RS Oph on April 2006.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=11cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg41.png) |

Figure 1:

Radial velocity curves and orbital solutions

for RS Oph. The data are phased with a period of 453.6 days and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG2.eps}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg58.png) |

Figure 2:

The standard error of the orbital semi-amplitude |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.05cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg59.png) |

Figure 3:

Phased radial velocities of the cF-absorption lines (dots) and the best circular solution (solid line) for the hot component based on the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,angle=90,clip]{Brandi_FIG4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg60.png) |

Figure 4:

Panels a) and b): profiles of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG5a.eps} \includegraphics[width=5cm,angle=90]{Brandi_FIG5b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg62.png) |

Figure 5:

Radial velocities and equivalent widths of the central absorptions of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg63.png) |

Figure 6:

Correlation of the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg71.png) |

Figure 7:

( Left) Presence of the Li I |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg72.png) |

Figure 8: Observed coronal lines in RS Oph on April 2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg73.png) |

Figure 9:

The He I and He II profiles showing a broad pedestal with the

strong narrow component at -15 and -23

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=9cm,clip]{Brandi_FIG10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/15/aa11417-08/Timg78.png) |

Figure 10:

Left panel: N III emission lines observed in

April 2006. The He II |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

and Na I

doublet during the quiescent period.

Blueshifted broad components in He I are present on April 2004 and September 2005.

The Na I doublet shows weak emission components and double structure in absorption.

and Na I

doublet during the quiescent period.

Blueshifted broad components in He I are present on April 2004 and September 2005.

The Na I doublet shows weak emission components and double structure in absorption.