| Issue |

A&A

Volume 529, May 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A50 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201016144 | |

| Published online | 31 March 2011 | |

Constraining tidal dissipation in F-type main-sequence stars: the case of CoRoT-11

1

INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, via S. Sofia 78,

95123

Catania,

Italy

e-mail: nuccio.lanza@oact.inaf.it

2

Research and Scientific Support Department,

European Space Agency, Keplerlaan 1, 2200AG,

Noordwijk, The

Netherlands

Received:

15

November

2010

Accepted:

18

February

2011

Context. Tidal dissipation in late-type stars is presently poorly understood and the study of planetary systems hosting hot Jupiters can provide new observational constraints to test proposed theories.

Aims. We focus on systems with F-type main-sequence stars and find that the recently discovered system CoRoT-11 is presently the best suited for this kind of investigation.

Methods. A classic constant tidal lag model is applied to reproduce the

evolution of the system from a plausible nearly synchronous state on the zero-age main

sequence (ZAMS) to the present state, thus putting constraints on the average modified

tidal quality factor  of its F6V star.Initial

conditions with the stellar rotation period longer than the orbital period of the planet

can be excluded on the basis of the presently observed state in which the star spins

faster than the planet orbit.

of its F6V star.Initial

conditions with the stellar rotation period longer than the orbital period of the planet

can be excluded on the basis of the presently observed state in which the star spins

faster than the planet orbit.

Results. It is found that  , if the system started

its evolution on the ZAMS close to synchronization, with an uncertainty related to the

constant tidal lag hypothesis and the estimated stellar magnetic braking within a factor

of ≈5–6.For a non-synchronous initial state of the system,

, if the system started

its evolution on the ZAMS close to synchronization, with an uncertainty related to the

constant tidal lag hypothesis and the estimated stellar magnetic braking within a factor

of ≈5–6.For a non-synchronous initial state of the system,

implies an age younger

than ~1 Gyr, while

implies an age younger

than ~1 Gyr, while  may be tested by

comparing the theoretically derived initial orbital and stellar rotation periods with

those of a sample of observed systems. Moreover, we discuss how the present value of

may be tested by

comparing the theoretically derived initial orbital and stellar rotation periods with

those of a sample of observed systems. Moreover, we discuss how the present value of

can be

measured by a timing of the mid-epoch and duration of the transits as well as of the

planetary eclipses to be observed in the infrared with an accuracy of ~0.5–1 s

over a time baseline of ~25 yr.

can be

measured by a timing of the mid-epoch and duration of the transits as well as of the

planetary eclipses to be observed in the infrared with an accuracy of ~0.5–1 s

over a time baseline of ~25 yr.

Conclusions. CoRoT-11 is a highly interesting system that potentially

allows us a direct measure of the tidal dissipation in an F-type star as well as the

detection of the precession of the orbital plane of the planet that provides us with an

accurate upper limit for the obliquity of the stellar equator. If the planetary orbit has

a significant eccentricity ( ), it

will be possible to also detect the precession of the line of the apsides and derive

information on the Love number of the planet and its tidal quality factor.

), it

will be possible to also detect the precession of the line of the apsides and derive

information on the Love number of the planet and its tidal quality factor.

Key words: planetary systems / planet-star interactions / binaries: close / stars: late-type / stars: rotation

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

1.1. Tidal dissipation theories

Tidal dissipation in close binary systems with late-type components is generally constrained by the ranges of orbital periods that correspond to circular orbits as observed in clusters of different ages. Ogilvie & Lin (2007) review recent observations and conclude that the equilibrium tide theory is insufficient to explain binary circularization by at least two orders of magnitude. Therefore, in addition to the dissipation of the kinetic energy of the flow associated with the tidal bulge, which is considered in the equilibrium tide theory (e.g., Zahn 1977, 1989), other effects must be included. The dynamical tide theory treats the dissipation of waves excited by the oscillating tidal potential in the stellar interior whose kinetic energy is ultimately extracted from the orbital motion. For simplicity, we shall assume that stars are rotating rigidly.

We consider a reference frame rotating with the stellar angular velocity

Ω = 2π/Prot, where

Prot is the stellar rotation period. In that frame, the

tidal potential experienced by the star can be written as a sum of rigidly rotating

components proportional to the spherical harmonics

Ylm(θ,φ), viz.,

![\hbox{${\rm Re}\, [\Psi_{l m} r^{l} Y_{m}^{l} (\theta, \phi) \exp(-{\rm i} \hat{\omega}_{lm} t) ]$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/05/aa16144-10/aa16144-10-eq13.png) , where (r,θ,φ)

are spherical polar coordinates with the origin in the centre of the star,

, where (r,θ,φ)

are spherical polar coordinates with the origin in the centre of the star,

is the tidal frequency in that frame, Ψlm the amplitude of the

component of degree l and azimuthal order m, and

t the time. The tidal frequency is given by

is the tidal frequency in that frame, Ψlm the amplitude of the

component of degree l and azimuthal order m, and

t the time. The tidal frequency is given by

,

where n = 2π/Porb is the

mean motion of the binary, Porb being its orbital period.

Waves are expected to be excited with the different frequencies

,

where n = 2π/Porb is the

mean motion of the binary, Porb being its orbital period.

Waves are expected to be excited with the different frequencies

that correspond to the various components of the tidal potential and their amplitudes will

depend on that of the exciting component and on the response of the stellar interior. For

a nearly circular orbit, the l = m = 2 component is the

dominant one and is responsible for the synchronization of the stellar rotation with the

orbital motion (e.g., Ogilvie & Lin 2004).

that correspond to the various components of the tidal potential and their amplitudes will

depend on that of the exciting component and on the response of the stellar interior. For

a nearly circular orbit, the l = m = 2 component is the

dominant one and is responsible for the synchronization of the stellar rotation with the

orbital motion (e.g., Ogilvie & Lin 2004).

Parameters of the transiting planetary systems having stars with Teff ≥ 6250 K.

The efficiency of tidal dissipation is usually parameterized by a dimensionless quality

factor Q proportional to the ratio of the total kinetic energy of the

tidal distortion to the energy dissipated in one tidal period

(e.g., Zahn 2008). In the theory,

Q always appears in the combination

Q′ ≡ (3/2)(Q/k2),

where k2 is the Love number of the star that measures its

density stratification1. Therefore, the lower the

value of Q′, the stronger the tidal dissipation. In general,

Q′ depends on l, m, and the tidal

frequency

(e.g., Zahn 2008). In the theory,

Q always appears in the combination

Q′ ≡ (3/2)(Q/k2),

where k2 is the Love number of the star that measures its

density stratification1. Therefore, the lower the

value of Q′, the stronger the tidal dissipation. In general,

Q′ depends on l, m, and the tidal

frequency  ,

thus a rigorous treatment of the tidal dissipation should consider the sum of the effects

associated with the different tidal components each having its specific

Q′. In practice, we adopt a single value of Q′ that

represents an average of the contributions of the different components. Moreover, we also

average on the tidal frequency, which means averaging along the evolution of a given

system, because the tidal frequency decreases with time and goes to zero when tidal

dissipation has circularized and synchronized the binary.

,

thus a rigorous treatment of the tidal dissipation should consider the sum of the effects

associated with the different tidal components each having its specific

Q′. In practice, we adopt a single value of Q′ that

represents an average of the contributions of the different components. Moreover, we also

average on the tidal frequency, which means averaging along the evolution of a given

system, because the tidal frequency decreases with time and goes to zero when tidal

dissipation has circularized and synchronized the binary.

The observations reviewed by Ogilvie & Lin

(2007) indicate that an average Q′ ranging between

5 × 105 and 2 × 106 is adequate to account for the circularization

of late-type main-sequence binaries. These low values require an efficient tidal

dissipation mechanism that Ogilvie & Lin

(2007), moving along the lines of previous work, propose to be the damping of

inertial waves in the stellar interior. These waves have the Coriolis force as their

restoring force and are excited provided that the tidal frequency

satisfies the relationship

satisfies the relationship  (1)The corresponding

Q′ has a remarkable dependence on the tidal and stellar rotation

frequencies owing to the complex details of wave excitation and dissipation that are still

poorly understood (cf. also Goodman & Lackner

2009). The main point, which can be regarded as firmly established, is that

Q′ decreases by 2−4 orders of magnitude when

(1)The corresponding

Q′ has a remarkable dependence on the tidal and stellar rotation

frequencies owing to the complex details of wave excitation and dissipation that are still

poorly understood (cf. also Goodman & Lackner

2009). The main point, which can be regarded as firmly established, is that

Q′ decreases by 2−4 orders of magnitude when

with respect to the case when

with respect to the case when  ,

because the excitation of inertial waves is forbidden in the latter case and only the

damping of the equilibrium tide contributes to the dissipation.

,

because the excitation of inertial waves is forbidden in the latter case and only the

damping of the equilibrium tide contributes to the dissipation.

In view of the present uncertainties in the dynamical tide theory, a precise determination of the tidal dissipation in binary systems with well known parameters is highly desirable. The case of F-type main-sequence stars is particularly challenging from a theoretical viewpoint because their internal structure consists of a thin outer convective zone and a radiative interior hosting a small convective core at the centre of the star. Since the propagation and dissipation of inertial waves are remarkably different in the convective and radiative zones, the study of F-type stars provides a critical test for the theory. Because the mass of the outer convection zone decreases rapidly with increasing stellar mass between 1.2 and 1.5 M⊙, the value of Q′ is expected to increase by 3−4 orders of magnitude within this mass range (Barker & Ogilvie 2009).

1.2. Testing tidal theory with planetary systems

A new opportunity to test the tidal theory comes from the star-planet systems, in particular those containing hot Jupiters. Systems with transiting planets have the best determined stellar and planetary parameters and are particularly suited to study tidal dissipation(see, e.g., Carone & Pätzold 2007). F-type host stars having a mass M ≥ 1.2−1.5 M⊙ evolve quite rapidly during their main-sequence lifetime, thus significantly improving their age estimate from model isochrone fitting in comparison with lower mass stars. A good age estimate is important to constrain the average value of Q′ by modelling the tidal evolution of a particular system (cf. Sect. 3.3). In Table 1 we list the presently known transiting systems with a star having an effective temperature Teff ≥ 6250 K, which corresponds to a spectral type earlier or equal to F8V.

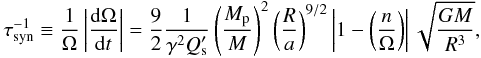

The columns from left to right list the name of the system, the effective temperature

Teff, the mass M and the radius

R of the star, its rotation period Prot, as

derived from the observed spectroscopic rotation broadening

vsini and the estimated stellar radius assuming an

equator-on view of the star, the orbital period Porb, the mass

Mp and radius Rp of the planet,

the timescale for the synchronization of the stellar rotation

τsyn, and the references. To compute the synchronization

time, we assume that the entire star is synchronized as is customary in tidal theory and

is suggested by the tidal evolution of close binaries observed in stellar clusters of

different ages. The synchronization timescale is then a measure of the strength of the

tidal dissipation in the star and is computed according to the formula  (2)where

γR ≃ 0.22 R is the gyration radius of the star

(Siess et al. 2000),

(2)where

γR ≃ 0.22 R is the gyration radius of the star

(Siess et al. 2000),

its modified

tidal quality factor, here assumed to be

its modified

tidal quality factor, here assumed to be  , a

the semimajor axis of the orbit, and G the gravitation constant (see

Mardling & Lin 2002). Equation (2) is valid for circular orbits and when the

spin axis is aligned with the orbital angular momentum. In this regard, the values given

here must be considered as estimates and for illustration purpose only, because high

eccentricity and/or obliquity have been measured for some of these systems.

, a

the semimajor axis of the orbit, and G the gravitation constant (see

Mardling & Lin 2002). Equation (2) is valid for circular orbits and when the

spin axis is aligned with the orbital angular momentum. In this regard, the values given

here must be considered as estimates and for illustration purpose only, because high

eccentricity and/or obliquity have been measured for some of these systems.

According to the dynamical tide theory by Ogilvie

& Lin (2007), the stars experiencing the strongest tidal interaction are

those with

n/Ω = Prot/Porb ≤ 2

because they have  when the l = m = 2 component of the tidal potential is

considered (Barker & Ogilvie 2009). For

these stars, the orbital decay (or expansion) owing to the tidal interaction can be

observed in principle. Among those systems, the best candidate is CoRoT-11 (Gandolfi et al. 2010) because it has a tidal

synchronization timescale in between those derived for systems like HD 197286/WASP-7 or

HAT-P-09, i.e., much longer than the main-sequence lifetime of the system, and those of,

e.g., OGLE-TR-9 or WASP-3 that are shorter than the expected ages of the systems, which

implies that the synchronous final state has possibly already been reached. Other systems,

e.g., HD15082/WASP-33, have a star so massive that a

when the l = m = 2 component of the tidal potential is

considered (Barker & Ogilvie 2009). For

these stars, the orbital decay (or expansion) owing to the tidal interaction can be

observed in principle. Among those systems, the best candidate is CoRoT-11 (Gandolfi et al. 2010) because it has a tidal

synchronization timescale in between those derived for systems like HD 197286/WASP-7 or

HAT-P-09, i.e., much longer than the main-sequence lifetime of the system, and those of,

e.g., OGLE-TR-9 or WASP-3 that are shorter than the expected ages of the systems, which

implies that the synchronous final state has possibly already been reached. Other systems,

e.g., HD15082/WASP-33, have a star so massive that a

too large to be

measurable is expected, or show a remarkable misalignment between the stellar spin and the

orbital angular momentum that makes the derivation of the rotation period from the

vsini quite uncertain, as in the case of XO-4.

too large to be

measurable is expected, or show a remarkable misalignment between the stellar spin and the

orbital angular momentum that makes the derivation of the rotation period from the

vsini quite uncertain, as in the case of XO-4.

In view of the peculiar characteristics ofthe CoRoT-11 system, we shall consider it for a

detailed study of the tidal evolution. We shall derive constraints on the average

value of its F6V

star by considering a possible initial state for the system when its star settled on the

ZAMS (see Sect. 2.4). Moreover, we shall demonstrate

how the present value of

value of its F6V

star by considering a possible initial state for the system when its star settled on the

ZAMS (see Sect. 2.4). Moreover, we shall demonstrate

how the present value of  can be

directly measured with suitable transit observations extended on a time interval of a few

decades.

can be

directly measured with suitable transit observations extended on a time interval of a few

decades.

2. Method: tidal evolution model and initial conditions

2.1. The constant quality-factor approximation

We adopt the classic equilibrium tidal model after Hut

(1981), in the formulation given by Leconte

et al. (2010). It assumes that the energy of the tidal perturbation raised by the

tidal potential is dissipated by viscous effects producing a constant

time lag Δt between the maximum of the tidal potential and the

tidal bulge. When Q ≫ 1,  ,

where

,

where  is the lag angle between the maximum of the deforming potential and the tidal bulge. Since

Δt is assumed to be constant during the tidal evolution,

Q and Q′ vary as

is the lag angle between the maximum of the deforming potential and the tidal bulge. Since

Δt is assumed to be constant during the tidal evolution,

Q and Q′ vary as

.

To model the evolution of a system by assuming a constant (or, better, an average)

Q′, we need to make an approximation. Following Leconte et al. (2010), we assume for the star and the planet

.

To model the evolution of a system by assuming a constant (or, better, an average)

Q′, we need to make an approximation. Following Leconte et al. (2010), we assume for the star and the planet

and

and

, where the indexes s and p

refer to the star and the planet, respectively, and nobs is

the present mean orbital motion of the system corresponding to the orbital period

Porb = 2.99433 days. As we shall see (cf. Sect. 3), the mean motion n varies by a factor

of ≈4−5 during the evolution of the system, but we shall neglect this change because

we are interested in deriving the order of magnitude of the average

, where the indexes s and p

refer to the star and the planet, respectively, and nobs is

the present mean orbital motion of the system corresponding to the orbital period

Porb = 2.99433 days. As we shall see (cf. Sect. 3), the mean motion n varies by a factor

of ≈4−5 during the evolution of the system, but we shall neglect this change because

we are interested in deriving the order of magnitude of the average

along the

evolution.

along the

evolution.

The theory of dynamical tides predicts that the dissipation is a complex function of the

tidal frequency, the properties of the interior of the body, and, possibly, the strength

of the tidal potential because of non-linear effects. All these dependencies are lumped

together into the coefficients  and

and

and in principle

could be included in an equilibrium model provided that the relationship between their

variations along the evolution of the system and the time lag value were known. In view of

our ignorance of the processes contributing to the tidal dissipation in stars and planets

(cf., e.g., Ogilvie & Lin 2004; Goodman & Lackner 2009) and the presently

limited observational constraints, we shall consider constant, i.e. average, values of

and in principle

could be included in an equilibrium model provided that the relationship between their

variations along the evolution of the system and the time lag value were known. In view of

our ignorance of the processes contributing to the tidal dissipation in stars and planets

(cf., e.g., Ogilvie & Lin 2004; Goodman & Lackner 2009) and the presently

limited observational constraints, we shall consider constant, i.e. average, values of

and

and

all along the

evolution and integrate the equations in Sect. 2.2 of Leconte et al. (2010) accordingly.

all along the

evolution and integrate the equations in Sect. 2.2 of Leconte et al. (2010) accordingly.

2.2. Range ofconsidered

The dynamical tide theory of Barker & Ogilvie

(2009) gives the dependence of  on the tidal

and the rotation frequencies of the star when the dissipation of inertial waves is

regarded as the main source of energy dissipation – see their Fig. 8, and consider that

on the tidal

and the rotation frequencies of the star when the dissipation of inertial waves is

regarded as the main source of energy dissipation – see their Fig. 8, and consider that

for a fixed ratio

for a fixed ratio  (cf. Sect. 3.6 of Ogilvie & Lin 2007). In

view of the simplified treatment of the interaction of these waves with turbulent

convection and radiative-convective boundaries, their results can be regarded only as an

approximation of the complex dependence of

(cf. Sect. 3.6 of Ogilvie & Lin 2007). In

view of the simplified treatment of the interaction of these waves with turbulent

convection and radiative-convective boundaries, their results can be regarded only as an

approximation of the complex dependence of  on the

relevant parameters. For a star of 1.2 M⊙ and

Prot ~ 1.5 days, the average

on the

relevant parameters. For a star of 1.2 M⊙ and

Prot ~ 1.5 days, the average

for

for

can be roughly estimated to be 5 × 107 with an uncertainty of at least one

order of magnitude and some preference for the lower bound because of the approximate

treatment of the above mentioned processes. Outside such a frequency range,

can be roughly estimated to be 5 × 107 with an uncertainty of at least one

order of magnitude and some preference for the lower bound because of the approximate

treatment of the above mentioned processes. Outside such a frequency range,

, i.e., the tidal

dissipation is reduced by at least three orders of magnitudes.

, i.e., the tidal

dissipation is reduced by at least three orders of magnitudes.

2.3. Range ofconsidered

An estimate of the tidal quality factor of the hot Jupiters may be based on astrometric

observations of the Jupiter-Io system that give  for Jupiter (see Lainey et al. 2009). Nevertheless, the quality factor

of hot Jupiters can be different from that of Jupiter owing to their different internal

structure. Assuming the observed eccentrity of the orbits of several hot Jupiters to be of

primordial origin, Matsumura et al. (2008) infer

for Jupiter (see Lainey et al. 2009). Nevertheless, the quality factor

of hot Jupiters can be different from that of Jupiter owing to their different internal

structure. Assuming the observed eccentrity of the orbits of several hot Jupiters to be of

primordial origin, Matsumura et al. (2008) infer

, with most of

the planets having

, with most of

the planets having  . Therefore, we

shall consider

. Therefore, we

shall consider  when integrating

the equation of tidal evolution of our system. The timescale to achieve the

pseudosynchronization of the planetary rotation for CoRoT-11 and of the other systems

containing hot Jupiters is of the order of 105 yr when

when integrating

the equation of tidal evolution of our system. The timescale to achieve the

pseudosynchronization of the planetary rotation for CoRoT-11 and of the other systems

containing hot Jupiters is of the order of 105 yr when

(cf. Sect. 2.2 of

Leconte et al. 2010). Even if

(cf. Sect. 2.2 of

Leconte et al. 2010). Even if

this timescale is

shorter than 3 × 107 yr, i.e., much shorter than the typical timescales for the

tidal evolution of the orbital parameters and the stellar spin. Therefore, we shall

consider the planet to be always in a state of pseudosynchronization, which simplifies the

integration of the tidal equations.

this timescale is

shorter than 3 × 107 yr, i.e., much shorter than the typical timescales for the

tidal evolution of the orbital parameters and the stellar spin. Therefore, we shall

consider the planet to be always in a state of pseudosynchronization, which simplifies the

integration of the tidal equations.

2.4. Initial state of the tidal evolution of planetary systems

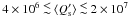

The observed distribution of the synchronization parameter n/Ω ≡ Prot/Porb provides us with information on the initial state of star-planet systems. We show n/Ω vs. the effective temperatureTeff of the host star for stars with Teff ≥ 6000 K in Fig. 1 where the most impressive feature is the lack of systems in the range 1 ≤ n/Ω ≤ 2, with the exception of HAT-P-09 and XO-3.

|

Fig. 1 Upper panel: the synchronization parameter n/Ω vs. the effective temperature of the star Teff in transiting planetary systems with Teff ≥ 6000 K. WASP-12 with n/Ω ≈ 33 has been omitted for the sake of clarity; lower panel: an enlargement of the lower portion of the upper panel to better show the domains close to n/Ω = 1 and n/Ω = 2, which are marked by horizontal dashed lines. The names of the systems are reported in both panels, although they are omitted for n/Ω ≤ 4.0 in the upper panel to avoid confusion. |

As conjectured by Lanza (2010), this may be

related to the processes occuring in the systems before their stars settle on the ZAMS.

After the planet forms in the circumstellar disc, it migrates inwards by transferring its

orbital angular momentum to the disc via resonant interactions (e.g., Lin et al. 1996). The migration ends where the orbital

period of the planet is half the orbital period of the particles at the inner edge of the

disc where it is truncated by the magnetic field of the protostar. Since the protostellar

magnetic field is also responsible for the locking of the stellar rotation to the inner

edge of the disc, the value of the synchronization ratio at this stage is

n/Ω ≡ Prot/Porb ≃ 2.

After a few million years, the disc disappears and the subsequent evolution depends on the

interplay between tidal and magnetic interactions coupling the star and the planet. As the

star contracts towards the ZAMS, it accelerates its rotation leading to a decrease of

n/Ω (cf. Fig. 8 of Lanza

2010). The loss of angular momentum through the stellar magnetized wind, however,

counteracts such an acceleration. If the lifetime of the disc is

Myr,

the contraction prevails and the system enters into the domain

n/Ω < 2 characterized by a strong tidal interaction due to the

dissipation of inertial waves in the extended convective envelope of the pre-main-sequence

star (Ogilvie & Lin 2007). Angular momentum

is transferred from the orbit to the spin of the star, leading to the infall of the planet

towards the star (Hut 1980). Considering a star

similar to the Sun,

Myr,

the contraction prevails and the system enters into the domain

n/Ω < 2 characterized by a strong tidal interaction due to the

dissipation of inertial waves in the extended convective envelope of the pre-main-sequence

star (Ogilvie & Lin 2007). Angular momentum

is transferred from the orbit to the spin of the star, leading to the infall of the planet

towards the star (Hut 1980). Considering a star

similar to the Sun,  , a planet of

Mp = 1 MJ, and an orbital

period of 3 days, eq. (8) of Ogilvie & Lin

(2007) gives an infall timescale of ≈250 Myr, which may account for the lack of

systems with 1 < n/Ω < 2 given that typical stellar ages

are between ~1 and ~8 Gyr.

, a planet of

Mp = 1 MJ, and an orbital

period of 3 days, eq. (8) of Ogilvie & Lin

(2007) gives an infall timescale of ≈250 Myr, which may account for the lack of

systems with 1 < n/Ω < 2 given that typical stellar ages

are between ~1 and ~8 Gyr.

On the other hand, if the magnetic braking prevails, the system may be driven into the

domain where n/Ω > 2 and the tidal interaction becomes so weak

( ) that the planet will

spiral towards the star on a timescale much longer than the main-sequence lifetime of the

star (Ogilvie & Lin 2007), thus populating

the region of the diagram where n/Ω > 2.Only when the planet is

more massive than ~5−10 MJ and the star is

late F or cooler, the tidal interaction may lead to the infall of the planet during the

main-sequence lifetime of the star (cf., e.g., Bouchy

et al. 2011).

) that the planet will

spiral towards the star on a timescale much longer than the main-sequence lifetime of the

star (Ogilvie & Lin 2007), thus populating

the region of the diagram where n/Ω > 2.Only when the planet is

more massive than ~5−10 MJ and the star is

late F or cooler, the tidal interaction may lead to the infall of the planet during the

main-sequence lifetime of the star (cf., e.g., Bouchy

et al. 2011).

Another possible scenario occurs when the magnetic field of the pre-main-sequence star is so strong (≈3−5 kG) as to effectively couple the orbital motion of the planet to the rotation of the star after the disc has disappeared (Lovelace et al. 2008; Vidotto et al. 2010). In this case, a synchronous state is attained on a timescale of ≈2−3 Myr and maintained until the field strength decreases rapidly as the star gets close to the ZAMS. If the magnetic braking prevails over the final stellar contraction, the system would reach the ZAMS with 1 < n/Ω < 2 and the planet will eventually fall into the star owing to the strong tidal interaction. On the contrary, if the stellar contraction prevails, the star will spin up, reach n/Ω < 1 on the ZAMS, and the tides will push the planet away from the star. This may explain why several systems populate the domain n/Ω < 1 in the diagram. The present value of n/Ω is lower than the initial value on the ZAMS because the tidal interaction transfers angular momentum from the stellar spin to the planetary orbit, leading to an increase of the semimajor axis. Thus we shall base our calculations on the hypothesis that the systems observed today with n/Ω ≤ 1, as CoRoT-11, have reached the ZAMS in a state close to synchronization.

Finally, a few remarks concerning the two systems that have 1 < n/Ω < 2. The peculiar state of the HAT-P-9 system having n/Ω ≃ 1.4 may be explained by the weakness of the tidal interaction owing to the relatively small planetary mass (~0.7 MJ), and/or the young age of the system. For XO-3, the system has significant measured eccentricity and projected obliquity (e = 0.288 and λ = 37.3 ± 3.7° respectively), so it is possible that the rotation period of the star is ill estimated or that the system has undergone a different evolution.

3. Application to CoRoT-11

3.1. System parameters

Gandolfi et al. (2010) present the observations leading to the discovery of CoRoT-11 and derive the parameters of the system that are reported in their Table 4 together with their uncertainties. The stellar rotation period can be inferred only from the observed vsini and the estimated radius of the star because no evidence of rotational modulation of the optical flux has been found in the CoRoT photometry. Indeed, a modulation with a period of ≈8 days appears in the photometric time series, but it is incompatible with the maximum rotation period of 1.73 ± 0.25 days as derived from the vsini = 40.0 ± 5 km s-1 and the star radius R = 1.37 ± 0.03 R⊙. It is likely to arise from a nearby contaminant star about 2 arcsec from CoRoT-11 that falls inside the CoRoT photometric mask.

The eccentricity of the planetary orbit is ill-constrained by the radial velocity curve because of the uncertainty of the radial velocity measurements for such a rapidly rotating F-type star. An upper limit of 0.2 comes from the modelling of the transit light curve that would lead to a mean stellar density that is incompatible with a F6V star for greater values. In any case, the present radial velocity and transit data are fully compatible with a circular orbit.

The angle λ between the projections of the stellar spin and the orbital

angular momentum on the plane of the sky can be measured through the Rossiter-McLaughlin

effect (e.g., Ohta et al. 2005). Owing to the

limited precision of the available measurements, Gandolfi

et al. (2010) could not measure λ, but they established that the

planet orbits in a prograde direction, i.e., in the same direction as the stellar

rotation, and that  . An aligned

system, i.e., having λ = 0°, is compatible with their observations. The

obliquity ϵ of the stellar equator with respect to the orbital plane of

the planet is given by

cosϵ = cosIpcosi + sinIpsinicosλ,

where Ip and i are the angles of inclination

of the orbital plane and the stellar equator to the plane of the sky. Since

. An aligned

system, i.e., having λ = 0°, is compatible with their observations. The

obliquity ϵ of the stellar equator with respect to the orbital plane of

the planet is given by

cosϵ = cosIpcosi + sinIpsinicosλ,

where Ip and i are the angles of inclination

of the orbital plane and the stellar equator to the plane of the sky. Since

,

cosϵ ≃ sinicosλ, thus the measurement

of λ provides us with a lower limit for the obliquity of the stellar

rotation axis.

,

cosϵ ≃ sinicosλ, thus the measurement

of λ provides us with a lower limit for the obliquity of the stellar

rotation axis.

3.2. Stellar magnetic braking

Late-type stars lose angular momentum through their magnetized stellar winds. For F-type

stars, Barker & Ogilvie (2009) assumed a

braking law of the form

(dΩ/dt)mb = −γwΩ3,

where γw = 1.5 × 10-15 yr is a factor that accounts

for the efficiency of magnetic braking. It can be integrated to give

Ω(t) = Ω0 [1 + γwΩ0(t − t0)] -0.5,

where Ω0 is the angular velocity at initial time

t0. For Ω ≪ Ω0 this yields the usual Skumanich

braking law of stellar rotation. Applying that equation to CoRoT-11a leads to an

unrealistically fast initial rotation for an age between 1 and 3 Gyr. Indeed, the above

law of angular momentum loss does not apply to fast rotators such as CoRoT-11a for which a

saturation of the angular momentum loss rate is required to explain the observed

distribution of stellar rotation periods (cf., e.g. Bouvier

et al. 1997). Therefore, we shall assume:  , where Ωsat is the

angular velocity that corresponds to the transition to the unsaturated regime. The value

of Ωsat for solar-mass stars is ≈8 Ω⊙, where Ω⊙ is

the angular velocity of the present Sun (Irwin &

Bouvier 2009). However, its value is highly uncertain in the case of mid-F stars

because they do not show a rotational modulation measurable from the ground and experience

a remarkably lower magnetic braking than G-type stars. Considering the data in Table 4 of

Wolff & Simon (1997), we estimate a

rotation period corresponding to saturation of ≈2.8 days for mid-F stars with

vsini ~ 20−25 km s-1 at the age

of the Hyades and the adopted value of γw. However, if

CoRoT-11a is older than ~2 Gyr, the value of the saturation period must be

longer by a factor of at least ≈2, otherwise the star would have been rotating faster

than the brake-up velocity on the ZAMS. This reduction of the angular momentum loss rate

in the saturated regime can be a consequence of the initially fast angular velocity that

led to a supersaturated dynamo regime for CoRoT-11a, or an effect of the close-in massive

planet that reduced the efficiency of the stellar wind to extract angular momentum from

the star (cf. Lanza 2010).

, where Ωsat is the

angular velocity that corresponds to the transition to the unsaturated regime. The value

of Ωsat for solar-mass stars is ≈8 Ω⊙, where Ω⊙ is

the angular velocity of the present Sun (Irwin &

Bouvier 2009). However, its value is highly uncertain in the case of mid-F stars

because they do not show a rotational modulation measurable from the ground and experience

a remarkably lower magnetic braking than G-type stars. Considering the data in Table 4 of

Wolff & Simon (1997), we estimate a

rotation period corresponding to saturation of ≈2.8 days for mid-F stars with

vsini ~ 20−25 km s-1 at the age

of the Hyades and the adopted value of γw. However, if

CoRoT-11a is older than ~2 Gyr, the value of the saturation period must be

longer by a factor of at least ≈2, otherwise the star would have been rotating faster

than the brake-up velocity on the ZAMS. This reduction of the angular momentum loss rate

in the saturated regime can be a consequence of the initially fast angular velocity that

led to a supersaturated dynamo regime for CoRoT-11a, or an effect of the close-in massive

planet that reduced the efficiency of the stellar wind to extract angular momentum from

the star (cf. Lanza 2010).

3.3. Backward integration from the present state to the initial condition

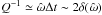

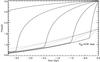

|

Fig. 2 Total angular momentum of the CoRoT-11 system in units of the critical angular

momentum as defined in Eq. (4.1) of Hut

(1980) versus the orbital mean motion in units of the present mean motion

nobs. The stellar magnetic braking law has

Psat = 6.0 days. The black solid line indicates the

total angular momentum values corresponding to tidal equilibrium. The black dotted

line represents the stability limit for the equilibrium as given by Eq. (4.2) of

Hut (1980). The solid blue lines show the

backward evolution of the system for different values of the tidal quality factor

|

We integrate the tidal evolution equations in Sect. 2.2 of Leconte et al. (2010) backwards in time starting from the present

condition, i.e., with the following parameters: stellar rotation period

Prot = 1.73 days, planet orbital period

Porb = 2.99433 days, star mass

M = 1.27 M⊙, star radius

R = 1.37 R⊙, planet mass

Mp = 2.33 MJ, planet radius

Rp = 1.43 RJ (where

MJ and RJ are the mass and

radius of Jupiter), orbital eccentricity e = 0, and stellar obliquity

ϵ = 0°. The stellar quality factor

is regarded as a

free parameter (see also Sect. 2.2).We account for

the angular momentum loss of the star due to its magnetized wind by adopting a saturated

loss rate with two possible values for

Psat = 2π/Ωsat, i.e., 6.0 or

8.0 days. Note that the results do not depend on the planet quality factor

is regarded as a

free parameter (see also Sect. 2.2).We account for

the angular momentum loss of the star due to its magnetized wind by adopting a saturated

loss rate with two possible values for

Psat = 2π/Ωsat, i.e., 6.0 or

8.0 days. Note that the results do not depend on the planet quality factor

, provided that the

orbital eccentricity is zero and the planet is assumed to be in the synchronous rotation

state.

, provided that the

orbital eccentricity is zero and the planet is assumed to be in the synchronous rotation

state.

The present state of the system and its backward evolution are represented in a tidal stability diagram similar to that of Hut (1980) in Fig. 2. The black solid line represents the value of the total angular momentum of the system when tidal equilibrium is established. For each value of the total angular momentum exceeding a minimum critical value (see Hut 1980), two equilibrium states are possible. The one on the left of the dotted line is stable, the other on the right is unstable. The filled square indicates the present state of the CoRoT-11 system with the assumption that i = 90°, i.e., the stellar rotation period is 1.73 days.

The results of the backward integrations of the tidal equations are represented by the

solid blue lines for different values of  and a braking

law with Psat = 6.0 days. All the backward evolutions

asymptotically approach an initial equilibrium state where all the time derivatives of the

relevant variables vanish. Such an equilibrium is unstable, i.e., it leads to the transfer

of angular momentum from the stellar spin to the planet that is pushed outwards.

Increasing the value of

and a braking

law with Psat = 6.0 days. All the backward evolutions

asymptotically approach an initial equilibrium state where all the time derivatives of the

relevant variables vanish. Such an equilibrium is unstable, i.e., it leads to the transfer

of angular momentum from the stellar spin to the planet that is pushed outwards.

Increasing the value of  the tidal

interaction weakens so that the evolution of the total angular momentum is dominated by

the magnetic braking of the star. This leads to an almost vertical evolution track in the

diagram since the star was initially rotating faster. There is no possible evolution track

that crosses the dashed line, indicating that the past system evolution has occured only

in the unstable region of the diagram, i.e., the planet has been pushed outwards starting

from its initial orbit with n/Ω < 1 during all the system

lifetime.

the tidal

interaction weakens so that the evolution of the total angular momentum is dominated by

the magnetic braking of the star. This leads to an almost vertical evolution track in the

diagram since the star was initially rotating faster. There is no possible evolution track

that crosses the dashed line, indicating that the past system evolution has occured only

in the unstable region of the diagram, i.e., the planet has been pushed outwards starting

from its initial orbit with n/Ω < 1 during all the system

lifetime.

Given that the initial state is unstable, integrating the tidal evolution equations backwards in time is recommended to ensure the stability of the obtained solutions. The instability of the present tidal state is not a specific property of CoRoT-11, but it is generally found in hot Jupiter systems (Levrard et al. 2009), most of which evolve towards the infall of the planet into the star. Therefore, what makes CoRoT-11 peculiar is the low value of the n/Ω ratio pushing the planet outwards.

|

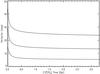

Fig. 3 Backward evolution of the orbital period Porb (solid

line) and the rotation period Prot (dotted line) vs.

time since the present epoch for different values of the modified tidal quality

factor |

The orbital period of the planet and the rotation period of the star are plotted vs. time

in Fig. 3 for Psat = 6.0

days. If the initial state of the system was characterized by a synchronization of the

stellar rotation with the planet orbital period, it is possible to constrain the tidal

quality factor, i.e.,  . Although we

speculated that the system may have reached the ZAMS close to synchronization in

Sect. 2.4, other evolutionary scenarios are

possible. In some of these scenarios, the planet may have started with an orbital period

longer than the stellar rotation period 3 Gyr ago, leading to the present state if

. Although we

speculated that the system may have reached the ZAMS close to synchronization in

Sect. 2.4, other evolutionary scenarios are

possible. In some of these scenarios, the planet may have started with an orbital period

longer than the stellar rotation period 3 Gyr ago, leading to the present state if

. As an example of such

an evolution, we plot in Fig. 3 the case of

. As an example of such

an evolution, we plot in Fig. 3 the case of

. Note that in this

case the initial state of the system has n/Ω ≃ 0.25 that is

significantly lower than the observed values of n/Ω plotted in

Fig. 1. Although the present sample of systems with

n/Ω < 1 is too small to draw conclusions on the minimum value

of n/Ω during their evolution, we hope that such a statistical

information can be used to constrain

. Note that in this

case the initial state of the system has n/Ω ≃ 0.25 that is

significantly lower than the observed values of n/Ω plotted in

Fig. 1. Although the present sample of systems with

n/Ω < 1 is too small to draw conclusions on the minimum value

of n/Ω during their evolution, we hope that such a statistical

information can be used to constrain  when a larger

sample is available.

when a larger

sample is available.

On the other hand,  implies a system

younger than ~1 Gyr. To illustrate this point, we plot in Fig. 3 the evolution for

implies a system

younger than ~1 Gyr. To illustrate this point, we plot in Fig. 3 the evolution for

for which the

system reached synchronization ~0.4 Gyr ago. Although the backward evolution

can be continued to earlier times, this initial state is unstable as well as all the

allowed initial states with

Porb > Prot. For

for which the

system reached synchronization ~0.4 Gyr ago. Although the backward evolution

can be continued to earlier times, this initial state is unstable as well as all the

allowed initial states with

Porb > Prot. For

, the tidal interaction

would be so strong and the evolution so fast that the system would reach a present value

of Porb longer than observed. Therefore, we can set a lower

limit on

, the tidal interaction

would be so strong and the evolution so fast that the system would reach a present value

of Porb longer than observed. Therefore, we can set a lower

limit on  on the basis

of the estimated age of the system. Note that if the system were younger than

~0.7−1 Gyr, the

on the basis

of the estimated age of the system. Note that if the system were younger than

~0.7−1 Gyr, the  value could

be so low that we might directly measure it after a few decades of timing observations

(see Sect. 4).

value could

be so low that we might directly measure it after a few decades of timing observations

(see Sect. 4).

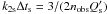

The evolution tracks obtained for Psat = 8.0 days and

different values of the average  are plotted

in Fig. 4. They show that a decrease of the braking

rate of CoRoT-11a by ~30 percent leads to a comparable decrease in the values

of the average

are plotted

in Fig. 4. They show that a decrease of the braking

rate of CoRoT-11a by ~30 percent leads to a comparable decrease in the values

of the average  because a

stronger tidal interaction is needed to transfer the required amount of angular momentum

from the stellar spin to the planet when the stellar rotation was initially slower. On the

other hand, if we adopt Psat = 2.8 days, as estimated from the

data of Wolff & Simon (1997), the stellar

braking was so rapid that only for a system younger than 1 Gyr we may find an acceptable

evolution with

because a

stronger tidal interaction is needed to transfer the required amount of angular momentum

from the stellar spin to the planet when the stellar rotation was initially slower. On the

other hand, if we adopt Psat = 2.8 days, as estimated from the

data of Wolff & Simon (1997), the stellar

braking was so rapid that only for a system younger than 1 Gyr we may find an acceptable

evolution with  . For higher values of

. For higher values of

, the

evolution takes longer, and this leads to a planet approaching the Roche lobe radius

and/or an initial stellar rotation exceeding the break-up velocity. Therefore, the

assumption that Psat is at least ~5−6 days seems

to be more likely for CoRoT-11a than Psat ~ 3−4

days. In the latter case, the system would be so young and the average

, the

evolution takes longer, and this leads to a planet approaching the Roche lobe radius

and/or an initial stellar rotation exceeding the break-up velocity. Therefore, the

assumption that Psat is at least ~5−6 days seems

to be more likely for CoRoT-11a than Psat ~ 3−4

days. In the latter case, the system would be so young and the average

so small that

we expect to detect the tidal increase of the orbital period within a few decades (see

Sect. 4).

so small that

we expect to detect the tidal increase of the orbital period within a few decades (see

Sect. 4).

|

Fig. 4 Backward evolution of the orbital period Porb (solid

line) and the rotation period Prot (dotted line) vs.

time since the present epoch for different values of the modified tidal quality

factor |

3.3.1. Initial eccentricity of the orbit

In the scenario introduced in Sect. 2.4, the

initial eccentricity of the planetary orbit would be close to zero (Sari & Goldreich 2004), unless an encounter

with some planetary or stellar body would have excited it. Assuming that no third body

has been perturbing the system after that event, the evolution of any primordial

eccentricity is ruled by the dissipation inside both the star and the planet, the latter

being the most important for  . The timescale

for the damping of the eccentricity

. The timescale

for the damping of the eccentricity  adopting the present parameters of the system is ~120 Myr for

e = 0.2,

adopting the present parameters of the system is ~120 Myr for

e = 0.2,  , and

, and

, and increases to

~1.1 Gyr for

, and increases to

~1.1 Gyr for  . Since the tidal

interaction was initially stronger – it scales as a-5 – the

initial τe was one order of magnitude shorter than the above

values, leading to a rapid damping of any initial eccentricity, unless

. Since the tidal

interaction was initially stronger – it scales as a-5 – the

initial τe was one order of magnitude shorter than the above

values, leading to a rapid damping of any initial eccentricity, unless

. Moreover, for

initially high eccentricities (i.e.,

. Moreover, for

initially high eccentricities (i.e.,  )

and an initial n/Ω ≈ 1, the evolution of the system may be

significantly affected and the infall of the planet occurs as the orbital angular

velocity at the periastron exceeds the stellar angular velocity. To prevent such an

infall, we must assume that the star was initially rotating remarkably faster than

considered above. Because the rotation braking on the main sequence is expected to be

small, this is hardly compatible with the present estimated rotation period. We conclude

that the present eccentricity of CoRoT-11 is likely to be close to zero. In any case, we

describe in Sect. 4 observations that can

constrain the present value of e to allow us to distinguish among

different scenarios for the system evolution.

)

and an initial n/Ω ≈ 1, the evolution of the system may be

significantly affected and the infall of the planet occurs as the orbital angular

velocity at the periastron exceeds the stellar angular velocity. To prevent such an

infall, we must assume that the star was initially rotating remarkably faster than

considered above. Because the rotation braking on the main sequence is expected to be

small, this is hardly compatible with the present estimated rotation period. We conclude

that the present eccentricity of CoRoT-11 is likely to be close to zero. In any case, we

describe in Sect. 4 observations that can

constrain the present value of e to allow us to distinguish among

different scenarios for the system evolution.

3.3.2. Initial obliquity of the orbit

The obliquity of the CoRoT-11 system may be significantly different from zero, as

indeed found for several stars accompanied by hot Jupiters with

Teff > 6250 K (Winn

et al. 2010). For a system born close to n/Ω = 1, we need

Ωcosϵ > n to prevent the tidal infall of the

planet, and the observational result that CoRoT-11 is compatible with an aligned system

agrees with this constraint. Initial values of the obliquity

ϵ > 30° require a fast-rotating star, which is difficult to

reconcile with the presently observed vsini and

stellar radius. However, lower values of the obliquity cannot be excluded. They are

damped on a timescale that depends on the value of

, as

illustrated in Fig. 5 where the time has been

scaled inversely to the stellar tidal quality factor. These plots show that after an

initial remarkable damping of the obliquity, it asymptotically approaches a value about

half its initial value that practically corresponds to the present value. In Sect. 4 we shall discuss how this value can be constrained

with accurate timing observations of the system.

, as

illustrated in Fig. 5 where the time has been

scaled inversely to the stellar tidal quality factor. These plots show that after an

initial remarkable damping of the obliquity, it asymptotically approaches a value about

half its initial value that practically corresponds to the present value. In Sect. 4 we shall discuss how this value can be constrained

with accurate timing observations of the system.

|

Fig. 5 Forward evolution of the obliquity from the ZAMS for different initial values of the angle itself. The planetary orbit is assumed circular and the initial orbital period is 0.7 days, while the initial rotation period of the star is 0.48 days for ϵ(t = 0) = 45°, 0.60 days for ϵ(t = 0) = 30°, and 0.67 days for ϵ(t = 0) = 15°, to prevent the infall of the planet. |

4. Measuring the present tidal dissipation

The main conclusion of the previous section is that the mean modified tidal quality factor

of CoRoT-11a  , provided that the

system started its evolution on the ZAMS from a nearly synchronous state. Since

, provided that the

system started its evolution on the ZAMS from a nearly synchronous state. Since

is subject to

remarkable variations during the evolution of the system, this result is of limited value to

constrain dynamical tide theory, as for the mean values of

is subject to

remarkable variations during the evolution of the system, this result is of limited value to

constrain dynamical tide theory, as for the mean values of

derived from

close binaries in clusters. However, a much more interesting opportunity offered by CoRoT-11

is the possibility to measure the present value of

derived from

close binaries in clusters. However, a much more interesting opportunity offered by CoRoT-11

is the possibility to measure the present value of  from the rate

of orbital period variation. Moreover, as we shall see, the rate of orbital period variation

also depends on the orbit parameters, and we can extract a wealth of information from

CoRoT-11 using the timing method.

from the rate

of orbital period variation. Moreover, as we shall see, the rate of orbital period variation

also depends on the orbit parameters, and we can extract a wealth of information from

CoRoT-11 using the timing method.

4.1. The circularized and aligned system hypothesis

If the present orbit is circular, the semimajor axis is subject to a secular increase

because the star is rotating faster than the orbital motion of the planet, so angular

momentum is transferred from the stellar spin to the orbit via the tidal interaction. When

e = 0 and the stellar obliquity is negligible

(ϵ ~ 0°), the rate of this transfer depends on the system

parameters, which are known to a good level of precision, and on

only. Therefore, we

can compute the rate of orbital period increase

dPorb/dt and use it to derive the

difference (O–C) between the observed time of mid-transit and that computed with a

constant period ephemeris after N orbital periods, viz.:

only. Therefore, we

can compute the rate of orbital period increase

dPorb/dt and use it to derive the

difference (O–C) between the observed time of mid-transit and that computed with a

constant period ephemeris after N orbital periods, viz.:  (3)where we have

assumed that the constant period of the ephemeris is the orbital period at

N = 0, i.e., at the epoch of the first transit. Using the tidal

evolution model of Leconte et al. (2010) and

assuming e = 0, ϵ = 0°, and the maximum stellar rotation

period Prot = 1.73 days, we find:

(3)where we have

assumed that the constant period of the ephemeris is the orbital period at

N = 0, i.e., at the epoch of the first transit. Using the tidal

evolution model of Leconte et al. (2010) and

assuming e = 0, ϵ = 0°, and the maximum stellar rotation

period Prot = 1.73 days, we find:  (4)after

N = 3000 orbital periods, i.e., 24.6 years.

(4)after

N = 3000 orbital periods, i.e., 24.6 years.

The epoch of mid transit can be determined with an accuracy that depends on the depth and

duration of the transit, the accuracy of the photometry, and the presence of noise

sources, e.g., related to stellar activity. In the case of CoRoT-11, because the star

shows no signs of magnetic activity, the precision of the transit timing is dominated by

the photometric accuracy. Gandolfi et al. (2010)

report in their Table 4 a precision of ~25 s for the initial epoch of their

ephemeris as obtained from a sequence of ~50 transits observed with a

photometric accuracy of ~250 parts per million (ppm) and a cadence of

~130 s. Recently, Winn et al. (2009)

using the Magellan/Baade 6.5-m telescope, observed two transits of the hot Jupiter

WASP-4b, reaching a photometric accuracy of ~500 ppm (standard deviation) in

their individual measurements obtained with a cadence of 30 s. The average standard

deviation of the epoch of mid-transit is ~5 s, which can be assumed as the

limit presently attainable with ground-based photometry. The transit of WASP-4b has a

depth of ≈0.028 mag and the star has a magnitude of V ≃ 12.5, while

that of CoRoT-11 has a depth of ≈0.011 mag and the star has V = 12.94.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a timing accuracy of 0.5−1 s can be reached

with a space-borne dedicated telescope of aperture 2−3 m, since the precision is

expected to scale with the accuracy of the photometry that should reach 200−300 ppm in

~15 s integration time. This instrument would allow us to detect the expected

transit time variation (hereafter TTV) with 3σ significance after an

interval of ~25 years for  . Even if no

significant TTV is detected, a stringent lower limit can be placed on

. Even if no

significant TTV is detected, a stringent lower limit can be placed on

, with the

sensitivity increasing as the square of the considered time baseline (cf. Eq. (3)).

, with the

sensitivity increasing as the square of the considered time baseline (cf. Eq. (3)).

4.2. The eccentric system hypothesis

A significant eccentricity of the planetary orbit can affect the O–C of the TTV,

particularly when tidal dissipation in the planet is not negligible. This happens because

the angular momentum of the planetary orbit is given by

![\hbox{$L_{\rm p} = [(M_{\rm s} M_{\rm p}/(M_{\rm s} + M_{\rm p})] n a^{2} \sqrt{1- e^{2}}$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/05/aa16144-10/aa16144-10-eq217.png) ,

so an increase of Lp does not necessarily lead to an increase

of a when the eccentricity is damped. Assuming e = 0.2,

,

so an increase of Lp does not necessarily lead to an increase

of a when the eccentricity is damped. Assuming e = 0.2,

, and

, and

, we find

O−C = −8.33 s after 24.6 yr, owing to the strong dissipation inside the planet that

dumps the eccentricity with a timescale of ~120 Myr. If the dissipation inside

the planet is weaker, the absolute value of the O–C decreases. For instance, if

, we find

O−C = −8.33 s after 24.6 yr, owing to the strong dissipation inside the planet that

dumps the eccentricity with a timescale of ~120 Myr. If the dissipation inside

the planet is weaker, the absolute value of the O–C decreases. For instance, if

, we obtain

O–C = 0.49 s after 24.6 yr.

, we obtain

O–C = 0.49 s after 24.6 yr.

Furthermore, if the orbit of CoRoT-11 is indeed eccentric, the measurement of the O–C of

the primary transit are not sufficient to determine

. This happens

because in addition to the tidal evolution, also the precession of the line of the apsides

(due to the planetary and stellar tidal deformations and general relativistic effects)

produces a TTV (see Miralda-Escudé 2002; Ragozzine & Wolf 2009). For

e = 0.2, and a planet Love number k2 = 0.3,

similar to that of Saturn, we have a precession period of only ~3300 yr, which

leads to a maximum O−C = 18.1 s after N = 3000 orbital periods, i.e.,

24.6 yr. To separate the effects of the apsidal precession from those of tidal origin, we

note that the apsidal precession produces an oscillation of the O–C of the mid of the

secondary eclipse, i.e., when the planet is occulted by the star, which is always shifted

in phase by 180° with respect to that of the primary transit. In other words, the two

oscillations have always opposite signs, as is well known for the apsidal precession of

close binaries (see, e.g., Gimenez et al. 1987). On

the other hand, the O–C of tidal origin has the same sign for both the primary transit and

the secondary eclipse, so it can be separated from that arising from apsidal precession.

. This happens

because in addition to the tidal evolution, also the precession of the line of the apsides

(due to the planetary and stellar tidal deformations and general relativistic effects)

produces a TTV (see Miralda-Escudé 2002; Ragozzine & Wolf 2009). For

e = 0.2, and a planet Love number k2 = 0.3,

similar to that of Saturn, we have a precession period of only ~3300 yr, which

leads to a maximum O−C = 18.1 s after N = 3000 orbital periods, i.e.,

24.6 yr. To separate the effects of the apsidal precession from those of tidal origin, we

note that the apsidal precession produces an oscillation of the O–C of the mid of the

secondary eclipse, i.e., when the planet is occulted by the star, which is always shifted

in phase by 180° with respect to that of the primary transit. In other words, the two

oscillations have always opposite signs, as is well known for the apsidal precession of

close binaries (see, e.g., Gimenez et al. 1987). On

the other hand, the O–C of tidal origin has the same sign for both the primary transit and

the secondary eclipse, so it can be separated from that arising from apsidal precession.

We conclude that a measurement of the eccentricity (or a determination of a more

stringent upper limit) is critical to derive  from the

O–C observations. A direct constraint on the eccentricity can be obtained from the

observation of the time of the secondary eclipse. Gandolfi

et al. (2010) did not find evidence of a secondary eclipse in the CoRoT light

curve, which sets an upper limit of ~100 ppm to its depth in the spectral range

300−1100 nm. However, it should be possible to detect the secondary eclipse in the

infrared, thus deriving the value of ecosω, where

ω is the longitude of the periastron, from the deviation of the time of

the secondary eclipse from half the orbital period. For HD 189733 Knutson et al. (2007) found, observing in a band centred at

8 μm with IRAC onboard of Spitzer, that the secondary eclipse occurred

120 ± 24 s after the time expected for a circular orbit, leading to

ecosω = 0.001 ± 0.0002. The same method has been

applied to constrain the eccentricity of the orbit of CoRoT-2 finding

ecosω = −0.00291 ± 0.00063 (Gillon et al. 2010). Moreover, the duration of the primary transit and

the secondary eclipse can provide a measurement of

esinω, although with a precision significantly poorer

than for the secondary eclipse timing (see Sect. 2.5 of Ragozzine & Wolf 2009). In conclusion, we recommend to perform infrared

photometry of CoRoT-11 to constrain its orbital eccentricity.

from the

O–C observations. A direct constraint on the eccentricity can be obtained from the

observation of the time of the secondary eclipse. Gandolfi

et al. (2010) did not find evidence of a secondary eclipse in the CoRoT light

curve, which sets an upper limit of ~100 ppm to its depth in the spectral range

300−1100 nm. However, it should be possible to detect the secondary eclipse in the

infrared, thus deriving the value of ecosω, where

ω is the longitude of the periastron, from the deviation of the time of

the secondary eclipse from half the orbital period. For HD 189733 Knutson et al. (2007) found, observing in a band centred at

8 μm with IRAC onboard of Spitzer, that the secondary eclipse occurred

120 ± 24 s after the time expected for a circular orbit, leading to

ecosω = 0.001 ± 0.0002. The same method has been

applied to constrain the eccentricity of the orbit of CoRoT-2 finding

ecosω = −0.00291 ± 0.00063 (Gillon et al. 2010). Moreover, the duration of the primary transit and

the secondary eclipse can provide a measurement of

esinω, although with a precision significantly poorer

than for the secondary eclipse timing (see Sect. 2.5 of Ragozzine & Wolf 2009). In conclusion, we recommend to perform infrared

photometry of CoRoT-11 to constrain its orbital eccentricity.

The present fast rotation of CoRoT-11a can in principle excite the eccentricity of the

orbit during the phase of the evolution when

Prot/Porb < 11/18

(cf. Eq. (6) of Leconte et al. 2010). However, the

tidal dissipation inside the planet is effective at damping the eccentricity and only for

we find an increasing

eccentricity for the present state of the system.Imposing that the eccentricity is always

damped along the past evolution of the system, we find

we find an increasing

eccentricity for the present state of the system.Imposing that the eccentricity is always

damped along the past evolution of the system, we find

for

for

.

.

4.3. Non-negligible obliquity hypothesis

If the present obliquity of the system is not negligible, the rate of orbital period

increase and the corresponding O–C in Eq. (4) must be multiplied by  (5)because the

component of the stellar angular momentum interacting with the orbit is

Lscosϵ, where

Ls is the modulus of the angular momentum of the star (cf.

Eq. (2) of Leconte et al. 2010).

(5)because the

component of the stellar angular momentum interacting with the orbit is

Lscosϵ, where

Ls is the modulus of the angular momentum of the star (cf.

Eq. (2) of Leconte et al. 2010).

It is interesting to note that the obliquity can be constrained not only through the observation of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect, but also by measuring the precession of the orbital plane of the planet around the total angular momentum of the system that is expected when ϵ ≠ 0°. This precession arises because the stellar gravitational quadrupole moment is non-negligible owing to its fast rotation. More precisely, adopting a stellar Love number k2s = 0.0138 after Claret (1995) and Prot = 1.73 days, we find J2 = 4.19 × 10-5. The contribution to J2 arising from the tidal deformation of the star induced by the planet is about 1100 times smaller and can be safely neglected.

Even assuming an obliquity of a few degrees, the precession period is so short as to give

measurable effects. For instance, for ϵ = 5°, the precession of the

orbital plane has a period of ~7.0 × 104 years, according to Eq. (4)

of Miralda-Escudé (2002). This produces a variation

of the length of the transit chord across the disc of the star that leads to a variation

of the transit duration (transit duration variation, hereafter TDV). Applying Eq. (12) of

Miralda-Escudé (2002) and assuming that the total

angular momentum of the system is approximately perpendicular to the line of sight, we

find a maximum TDV of ~8 s in one year. Assuming a precision of

~40 s in the measurement of the duration of the transit as obtained with CoRoT

observations, this variation should be easily detected in ~5 yr and can provide

a lower limit for the stellar obliquity, which is remarkably better than what is

achievable with the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect if  .

.

5. Role of a possible third body

The use of TTV to measure the tidal dissipation inside the star (and the planet, in the case of an eccentric orbit) can be hampered by the presence of a distant third body that induces apparent O–C variations owing to the light-time effect related to the revolution of the star-planet system around the common centre of mass. In principle, any light-time effect induced by a third body is periodic while the effects of tidal dissipation are secular, i.e., they do not change sign. However, if the orbital period of the third body around the barycentre of the system is longer than, say, three times the time baseline of our observations, it may become difficult or impossible to separate the two effects.

To be specific, let us consider an O–C of 3 s observed with a time baseline of ΔT ~ 25 yr. If it is caused by a light-time effect, the corresponding radial motion of the star-planet system is Δz = c(O−C) ~ 109 m, where c is the speed of light, and the radial velocity of the barycentre of the system is Δz/ΔT ≃ 1.26 m s-1, too small to be detectable with the present radial velocity accuracy (cf. Gandolfi et al. 2010). A third body moving on a coplanar circular orbit with a period of, say, Ptb = 75 yr, would have an orbital semimajor axis of ~2.88 × 1012 m and a minimum mass of 0.2 MJ to induce a reflex motion of the above amplitude. Its direct detection is very difficult because its apparent separation from the central star would be only 0.034 arcsec, given an estimated distance to CoRoT-11 of 560 ± 30 pc. Astrometric measurements with the GAIA or SIM satellites cannot be used to detect the reflex motion of CoRoT-11 because it would correspond to a maximum displacement of only ~2.4 μarcsec during an interval of 5 yr, which is impossible to separate from the much larger proper motion of the system.

If the orbit of the third body is inclined to the orbital plane of the star-planet system, the orbital plane of the planet will precede around the total angular momentum of the system. Assuming a third body mass of 0.2 MJ, a relative inclination of the orbits of 45°, and a semimajor axis of ~2.88 × 1012 m, equal to ~20 AU, Eq. (8) of Miralda-Escudé (2002) gives a precession period of ~14 Gyr, i.e., too long to be observable.

Secular perturbations of the orbit of the planet by the distant third body can be neglected because they induce a variation of the O–C of the order of Porb/Ptb ~ 10-4 of the light-time effect (cf., e.g., Borkovits et al. 2003). On the other hand, a perturber on a close-in orbit, possibly in resonance with the planet, would induce O–C variations with a short periodicity and an amplitude up to a few minutes (Agol et al. 2005), which would be easily detectable.

It is interesting to note that CoRoT-11a has a low level of magnetic activity in contrast to stars with lower effective temperature. This implies that the orbital period modulation induced by magnetic activity (Lanza et al. 1998; Lanza 2006) can be excluded as a source of O–C variations in this case. This is not possible for cooler stars (Watson & Marsh 2010) which are therefore less suitable to measure the TTV induced by tidal dissipation.

6. Conclusions

Assuming an initial state of the CoRoT-11 system close to synchronization between the

stellar spin and the orbital period of the planet, we can put constraints on the average

modified tidal quality factor of its F-type star, finding

. Rigorously speaking, we

should have expressed these constraints in terms of the average tidal time lag

Δt because our tidal equations are valid for a constant

Δt (cf. Sect. 2 and Leconte et al. 2010). However, in view of the uncertainty

on the above constraints, we prefer to give them in terms of

. Rigorously speaking, we

should have expressed these constraints in terms of the average tidal time lag

Δt because our tidal equations are valid for a constant

Δt (cf. Sect. 2 and Leconte et al. 2010). However, in view of the uncertainty

on the above constraints, we prefer to give them in terms of

that varies by

a factor up to ≈4−5 during the evolution, if Δt is assumed to be

constant (cf. Sects. 2 and 3.3).

that varies by

a factor up to ≈4−5 during the evolution, if Δt is assumed to be

constant (cf. Sects. 2 and 3.3).

An initial state close to synchronization is not the only possible one. However, the

minimum estimated age of the system of ~1 Gyr implies

, otherwise the evolution

from any initial state with

Porb > Prot would be too

fast, leading to a present Porb longer than observed. An upper

limit on

, otherwise the evolution

from any initial state with

Porb > Prot would be too

fast, leading to a present Porb longer than observed. An upper

limit on  can be set when

a larger statistics of the values of the

n/Ω = Prot/Porb

ratio will be available because for

can be set when

a larger statistics of the values of the

n/Ω = Prot/Porb

ratio will be available because for  the initial value of

n/Ω is predicted to be ~0.25 that is smaller than the

presently observed minimum n/Ω ~ 0.5 (see Sect. 3.3).

the initial value of

n/Ω is predicted to be ~0.25 that is smaller than the

presently observed minimum n/Ω ~ 0.5 (see Sect. 3.3).

The above limits on  are only a

factor of 2−15 smaller than the average value predicted by Barker & Ogilvie (2009), which can be considered a success of the dynamic

tide theory of Ogilvie & Lin (2007) given the

current uncertainty on the tidal dissipation processes occurring in stellar convection

zones.

are only a

factor of 2−15 smaller than the average value predicted by Barker & Ogilvie (2009), which can be considered a success of the dynamic

tide theory of Ogilvie & Lin (2007) given the

current uncertainty on the tidal dissipation processes occurring in stellar convection

zones.

We find that CoRoT-11 is one of the best candidates to look for orbital period variations

related to tidal evolution by monitoring its transits and secondary eclipses in the optical

and in the infrared passbands. In contrast to several systems hosting very hot Jupiters,

e.g., WASP-12 or WASP-18, whose orbital decay may be too slow to be measurable (Ogilvie & Lin 2007; Li et al. 2010), the parameters of CoRoT-11 appear to be ideal for a

detection by measuring the times of mid-transit and mid-eclipse with an accuracy of at least

1−5 s along a time baseline of ~25 yr. This is a consequence of the peculiar

ratio of the rotation period of the star to the orbital period of the planet that is

presently the smallest among systems having a radial velocity curve compatible with zero

eccentricity. The test is particularly sensitive to values of

between

105 and 106, leading to a fast tidal evolution of the system, as

discussed in Sect. 3.3.

between

105 and 106, leading to a fast tidal evolution of the system, as

discussed in Sect. 3.3.

The CoRoT-11 system is also particular because the precession of the orbital plane due to a