| Issue |

A&A

Volume 525, January 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A155 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201015479 | |

| Published online | 10 December 2010 | |

Alfvén wave phase-mixing and damping in the ion cyclotron range of frequencies

1

School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St.

Andrews,

St. Andrews,

Fife

KY16 9SS,

UK

e-mail: jamest@mcs.st-and.ac.uk; ineke@mcs.st-and.ac.uk

2

EURATOM/CCFE Fusion Association, Culham Science Centre, Abingdon,

Oxfordshire,

OX14 3DB,

UK

e-mail: k.g.mcclements@ccfe.ac.uk

Received:

27

July

2010

Accepted:

18

October

2010

Aims. We determine the effect of the Hall term in the generalised Ohm’s law on the damping and phase mixing of Alfvén waves in the ion cyclotron range of frequencies in uniform and non-uniform equilibrium plasmas.

Methods. Wave damping in a uniform plasma is treated analytically, whilst a Lagrangian remap code (Lare2d) is used to study Hall effects on damping and phase mixing in the presence of an equilibrium density gradient.

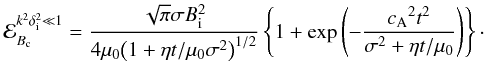

Results. The magnetic energy associated with an initially Gaussian field

perturbation in a uniform resistive plasma is shown to decay algebraically at a rate that

is unaffected by the Hall term to leading order in  where k is wavenumber and δi is ion skin

depth. A similar algebraic decay law applies to whistler perturbations in the limit

where k is wavenumber and δi is ion skin

depth. A similar algebraic decay law applies to whistler perturbations in the limit

. In a

non-uniform plasma it is found that the spatially-integrated damping rate due to phase

mixing is lower in Hall MHD than it is in MHD, but the reduction in the damping rate,

which can be attributed to the effects of wave dispersion, tends to zero in both the weak

and strong phase mixing limits.

. In a

non-uniform plasma it is found that the spatially-integrated damping rate due to phase

mixing is lower in Hall MHD than it is in MHD, but the reduction in the damping rate,

which can be attributed to the effects of wave dispersion, tends to zero in both the weak

and strong phase mixing limits.

Key words: plasmas / waves / magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) / Sun: flares / Sun: chromosphere

© ESO, 2010

1. Introduction

The interaction between Alfvén waves and plasma inhomogeneities forms a well-studied and important area of research, for both laboratory and astrophysical plasmas. One process which arises as a result of this interaction is Alfvén wave phase-mixing. Early studies of Alfvén wave phase-mixing demonstrated a potential for significantly enhanced plasma heating. In particular, Heyvaerts & Priest (1983) proposed the phase-mixing of Alfvén waves as a potential solar coronal heating mechanism through enhanced wave-dissipation. They outlined that for a magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) treatment of initially planar shear-Alfvén waves, propagating independently on individual magnetic surfaces, large differences in phase are quickly generated between waves on neighbouring field lines, as a result of variation in Alfvén speed across the field. These phase-differences generate progressively smaller scales, and dramatically enhance the effects of viscous and Ohmic dissipation, in the locations where the Alfvén speed gradient is steepest.

This initial concept has been subsequently adapted for a variety of problems using MHD, based on the premise that the waves in question arise as a result of an infinite series of boundary motions at the photosphere. For example, this treatment has been used to investigate the heating of open magnetic field lines under various conditions, e.g. by Parker (1991); Hood et al. (1997); De Moortel et al. (1999, 2000). Phase-mixing has also been studied as a source of non-linear coupling to other wave modes (see, e.g. Nakariakov et al. 1997; Botha et al. 2000).

Of particular interest for this paper is the work of Hood et al. (2002). They note that an infinite series of boundary motions is unrealistic and instead investigate the effect on the amplitude damping rate due to phase-mixing when the waves are driven by only one or two initial impulsive motions at the boundary.

Recent studies have also begun to move away from the original MHD treatment, instead focussing on full kinetic descriptions of a plasma undergoing phase-mixing in a collisionless regime, as a potential mechanism for electron acceleration (see, e.g. Génot et al. 2004; Tsiklauri et al. 2005; Tsiklauri & Haruki 2008; Bian & Kontar 2010). On the assumption that the wavelengths of interest (λ) are small compared to the particle mean free path λmfp, Tsiklauri et al. (2005) and Bian & Kontar (2010) model the corona as a collisionless plasma and cite Landau damping as their primary wave dissipation mechanism. Such damping is strongly suppressed if λ ≫ λmfp (Ono & Kulsrud 1975), as in the case of propagating EUV disturbances with periods of tens or hundreds of seconds (see e.g. De Moortel 2009, and references therein), and a fluid model is then appropriate for the coronal plasma. On the other hand for waves with frequencies approaching the ion cyclotron frequency, typical coronal parameters correspond to classical (Spitzer) collisional mean free paths that exceed λ, suggesting instead the validity of the collisionless approach. However, Craig & Litvinenko (2002) have shown that it is not appropriate to use classical resistivity under flaring conditions because it implies current scale lengths that are several orders of magnitude shorter than λmfp, and moreover is inconsistent with the electric fields required to account for the observed acceleration of protons to tens of MeV on timescales of the order of one second (Hamilton et al. 2003). Craig & Litvinenko proposed that the effective resistivity under flaring conditions (specifically in a reconnecting current sheet) is determined by turbulence arising from electron-ion drift (e.g. ion acoustic) instabilities, and deduced that this effective resistivity could exceed the classical value by a factor of around 106. Under these circumstances a fluid model can be appropriate even for relatively high frequency waves. This may also be true in the upper chromosphere, where the plasma is both cooler and denser (and consequently much more collisional) than in the corona.

It is well known that the electron inertia term in the generalised Ohm’s law becomes comparable to the MHD terms when the system lengthscale approaches the electron skin depth, δe, which in a low beta plasma can exceed the ion Larmor radius. Moreover for perturbations with frequencies approaching the ion cyclotron frequency Ωi, the Hall term in the generalised Ohm’s law becomes as important as the MHD terms when the lengthscale of the system approaches the ion skin depth δi ( ≫ δe). When the introduction of the Hall term into Ohm’s law is the only modification made to the otherwise standard set of MHD equations, we may refer to this as a Hall MHD system.

Hall MHD has been found to be important for a number of fundamental plasma processes. For example, in magnetic reconnection studies, Birn et al. (2001) found that all models which included Hall dynamics returned indistinguishable reconnection rates, concluding that the inclusion of the Hall term is the minimum requirement for fast reconnection (for a summary of Geospace Environmental Modelling (GEM) challenge results, see Birn & Priest 2007).

High frequency waves (i.e. with frequencies ω ~ Ωi), have been observed in a range of astrophysical plasma systems, for example in the solar corona (summarised in Marsch 2006) and in situ, at the Earth’s bow shock (Sckopke et al. 1990). When oscillations in this frequency range are excited in collision-dominated plasmas, such that the collisional mean free path is less than the wavelength, it is then appropriate to use a Hall MHD model.

The goal of our work is to determine the extent to which the main consequences of phase-mixing (wave dissipation and plasma heating) are affected solely by the addition of the Hall term to Ohm’s law. To do this, we first investigate the damping rate of a uniform plasma using Hall MHD (Sect. 2). Phase-mixing is then included, by allowing the equilibrium density to vary (Sect. 2.3). Numerical simulations of a Hall MHD system, with various density profiles and Hall term strengths, are described in Sect. 3. We interpret these results and present conclusions in Sect. 4.

2. Wave damping analysis

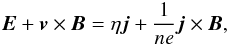

The Hall MHD form of Ohm’s Law is

where

E and B are electric and

magnetic fields, v is the single-fluid plasma velocity,

j is current density, η is electrical

resistivity, n is plasma number density and − e is

electron charge. Linearising the induction equation corresponding to this form of Ohm’s law,

together with the equation of motion (neglecting the pressure gradient force), for a plasma

with a uniform equilibrium field

B0 = B0ŷ

for a constant B0, uniform number density and resistivity, and

zero equilibrium flow, gives:

where

E and B are electric and

magnetic fields, v is the single-fluid plasma velocity,

j is current density, η is electrical

resistivity, n is plasma number density and − e is

electron charge. Linearising the induction equation corresponding to this form of Ohm’s law,

together with the equation of motion (neglecting the pressure gradient force), for a plasma

with a uniform equilibrium field

B0 = B0ŷ

for a constant B0, uniform number density and resistivity, and

zero equilibrium flow, gives: ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:HallInduct_L} \frac{\partial{\vec{B}_1}}{\partial t}&\!\!=\!\!&\curl\left({{\vec{v}}\times{\vec{B}_0}}\right)+\frac{\eta}{\muo}\boldnabla^2{\vec{B}_1} \!-\!\frac{1}{\muo ne}\curl\left[\left(\curl{\vec{B}_1}\right)\times{\vec{B}_0} \right] \\ \label{eq:EOM_L} \frac{\partial{\vec{v}}}{\partial{t}}&=&\frac{1}{{\rho_0}\muo}\left(\curl{\vec{B}_1}\right)\times{\vec{B}_0}, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/01/aa15479-10/aa15479-10-eq23.png) where

B1 [ = (Bx,0,Bz) ]

now represents a transverse perturbation to the equilibrium field,

ρ0 is equilibrium mass density, and

μ0 is the permeability of free space. Note that although, for

simplicity, we neglect plasma pressure, by assuming β = 0 in this

analytical treatment (as Alfvén, whistler and ion cyclotron waves are all incompressible in

a linear regime), the numerical simulations presented in Sect. 3 incorporate plasma pressure, i.e. β ≠ 0.

where

B1 [ = (Bx,0,Bz) ]

now represents a transverse perturbation to the equilibrium field,

ρ0 is equilibrium mass density, and

μ0 is the permeability of free space. Note that although, for

simplicity, we neglect plasma pressure, by assuming β = 0 in this

analytical treatment (as Alfvén, whistler and ion cyclotron waves are all incompressible in

a linear regime), the numerical simulations presented in Sect. 3 incorporate plasma pressure, i.e. β ≠ 0.

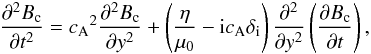

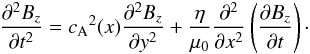

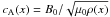

By inserting (2) into the time derivative

of (1) in the usual manner, the linearised

Alfvén wave equation is then modified:  (3)where

we have expressed transverse field perturbations in the form of a complex variable

Bc = Bz + iBx,

and introduced the Alfvén speed,

(3)where

we have expressed transverse field perturbations in the form of a complex variable

Bc = Bz + iBx,

and introduced the Alfvén speed,  ,

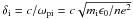

and the ion skin depth,

,

and the ion skin depth,  ,

where mi is the ion mass, c is the speed of

light, and ϵ0 is the permittivity of free space.

,

where mi is the ion mass, c is the speed of

light, and ϵ0 is the permittivity of free space.

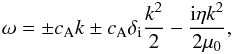

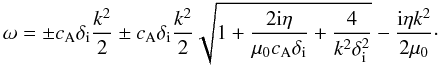

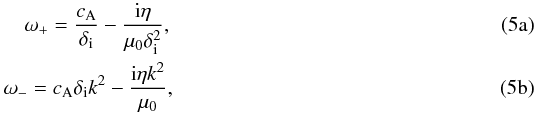

Seeking wave-like solutions of the form exp(i[ky − ωt])

allows us to form a dispersion relation to express perturbation frequencies,

ω, as a function of wavenumber k. By considering only

the regime of weak damping ( ), we obtain two separate solutions

depending on the size of the parameter

), we obtain two separate solutions

depending on the size of the parameter  . Taking first the

case of

. Taking first the

case of  , we make use of a simple Taylor

expansion to find (to leading order in

, we make use of a simple Taylor

expansion to find (to leading order in  ):

):  (4)which describes a shear

Alfvén wave, modified by Hall effects, and subject to resistive damping.

(4)which describes a shear

Alfvén wave, modified by Hall effects, and subject to resistive damping.

Considering the opposite case, when  , we find:

, we find:

Including the next term in

the Taylor expansion, we find two distinct forward propagating solutions:

Including the next term in

the Taylor expansion, we find two distinct forward propagating solutions:  where

in this limit, we now obtain a combination of whistler and ion cyclotron (i.c.) waves, both

subject to a form of resistive damping.

where

in this limit, we now obtain a combination of whistler and ion cyclotron (i.c.) waves, both

subject to a form of resistive damping.

2.1. Long wavelength Hall MHD regime (uniform)

We can examine the effect of this difference in behaviour of both

regimes, by

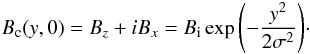

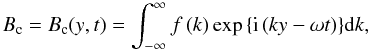

focussing on the evolution of an initially Gaussian pulse (of width σ,

and amplitude Bi), which is allowed to travel along the

equilibrium field, taking the form:

regimes, by

focussing on the evolution of an initially Gaussian pulse (of width σ,

and amplitude Bi), which is allowed to travel along the

equilibrium field, taking the form:  (6)Our complex variable can

be interpreted as a Fourier integral, evolving in time as:

(6)Our complex variable can

be interpreted as a Fourier integral, evolving in time as:  (7)with

f(k) determined by the initial conditions:

(7)with

f(k) determined by the initial conditions:

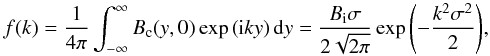

(8)where we have used the

standard result (Abramowitz & Stegun 1964,

Eq. (7.4.6)):

(8)where we have used the

standard result (Abramowitz & Stegun 1964,

Eq. (7.4.6)):  (9)We also use this result

to evaluate the integral in Eq. (7) in the

limit

(9)We also use this result

to evaluate the integral in Eq. (7) in the

limit  , finding:

, finding: ![\begin{equation} B_{\rm c}=\sum_{+,-}\frac{B_{\rm i}}{{\sqrt{1+\left(\frac{\eta}{\muo}-{\rm i}\ca\di \right)\frac{t}{\sigma^2} }}} {\exp{\left( \frac{-\left(y\pm\ca t \right)^2}{2\left[\sigma^2+\left(\frac{\eta}{\muo}-{\rm i}\ca\di\right)t\right] }\right) }} \label{eq:B_c(y,t)} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/01/aa15479-10/aa15479-10-eq52.png) (10)where

the summation is over forward- and backward-propagating waves. Equation (10) describes a pair of pulses travelling in

opposite direction at approximately the Alfvén speed, which are damped by finite

resistivity and circularly polarised. We can also calculate the contribution to the total

energy per unit area in (x, z),

ℰBTOT, made by the magnetic energy per unit

area in (x, z) of both pulses

(ℰBc) as follows:

(10)where

the summation is over forward- and backward-propagating waves. Equation (10) describes a pair of pulses travelling in

opposite direction at approximately the Alfvén speed, which are damped by finite

resistivity and circularly polarised. We can also calculate the contribution to the total

energy per unit area in (x, z),

ℰBTOT, made by the magnetic energy per unit

area in (x, z) of both pulses

(ℰBc) as follows:

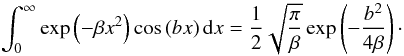

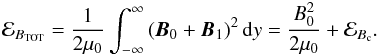

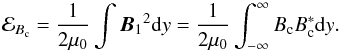

Since the magnetic

perturbation is transverse to the equilibrium field,

B0·B1 = 0

and hence

Since the magnetic

perturbation is transverse to the equilibrium field,

B0·B1 = 0

and hence  (11)Many of the factors

in

(11)Many of the factors

in  will cancel

upon integration, hence the energy associated with the pulse

(ℰBc) evolves as:

will cancel

upon integration, hence the energy associated with the pulse

(ℰBc) evolves as:  (12)Thus after a short

initial transient phase (essentially the time taken for an Alfvén wave to travel a

distance equal to the initial pulse width, σ), we recover a power law

decay (∝t −1/2 for

t ≫ μ0σ2 / η)

in the energy associated with the pulse. This expression (Eq. (12)) is compared with several numerical

simulation results in Sect. 3, and can be seen in

Fig. 2. It is straightforward to show that the

expression given by Eq. (12) for the Hall

MHD long wavelength (

(12)Thus after a short

initial transient phase (essentially the time taken for an Alfvén wave to travel a

distance equal to the initial pulse width, σ), we recover a power law

decay (∝t −1/2 for

t ≫ μ0σ2 / η)

in the energy associated with the pulse. This expression (Eq. (12)) is compared with several numerical

simulation results in Sect. 3, and can be seen in

Fig. 2. It is straightforward to show that the

expression given by Eq. (12) for the Hall

MHD long wavelength ( ) regime is identical

to that found for an initially Gaussian pulse in the MHD limit.

) regime is identical

to that found for an initially Gaussian pulse in the MHD limit.

2.2. Short wavelength Hall MHD regime (uniform)

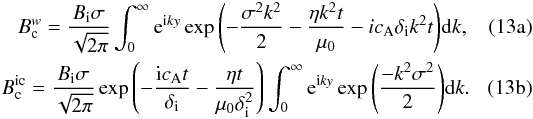

Turning to the opposite limit,  , the perturbation

frequencies (5b) comprise of a

combination of resistively damped whistler and ion cyclotron waves. We can again describe

the pulse evolution associated with each separate wave branch in this limit, in the manner

described previously (Sect. 2.1), again for an

initially Gaussian perturbation. Beginning with (7), and with the same initial conditions (8) as the previous limit, we find that the whistler wave calculation

proceeds similarly to that of the previous section, however the i.c. wave (being

independent of wavenumber) differs somewhat:

, the perturbation

frequencies (5b) comprise of a

combination of resistively damped whistler and ion cyclotron waves. We can again describe

the pulse evolution associated with each separate wave branch in this limit, in the manner

described previously (Sect. 2.1), again for an

initially Gaussian perturbation. Beginning with (7), and with the same initial conditions (8) as the previous limit, we find that the whistler wave calculation

proceeds similarly to that of the previous section, however the i.c. wave (being

independent of wavenumber) differs somewhat:  Evaluating

the integrals in Eq. (13b), using

Eq. (9), we obtain:

Evaluating

the integrals in Eq. (13b), using

Eq. (9), we obtain: ![\begin{subequations} \begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:Bcw2} B_{\rm c}^{w}\!=\!\frac{B_{\rm i}}{{\sqrt{1+2\left(\frac{\eta}{\muo}-{\rm i}\ca\di \right)\frac{t}{\sigma^2} }}} {\exp{\left( \frac{-y^2}{2\left[\sigma^2+2\left(\frac{\eta}{\muo}-{\rm i}\ca\di\right)t\right] }\right) }} \\ \label{eq:Bcic2} B_{\rm c}^{\rm ic}=B_{\rm i}\exp{\left(-\frac{ {\rm i}\ca t}{\di}-\frac{\eta t}{\muo\di^2} \right) } \exp{\left(-\frac{y^2}{2\sigma^2} \right) }\cdot \end{eqnarray} \label{eq:Bclarge} \end{subequations}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/01/aa15479-10/aa15479-10-eq66.png) In

this short wavelength (

In

this short wavelength ( ) regime, the peak of the pulse

now no longer propagates, but decreases in amplitude. The right circularly polarised

component of the pulse rapidly broadens, due to the high whistler speed, and damps

algebraically at a rate similar to that found in both the MHD and long wavelength

(

) regime, the peak of the pulse

now no longer propagates, but decreases in amplitude. The right circularly polarised

component of the pulse rapidly broadens, due to the high whistler speed, and damps

algebraically at a rate similar to that found in both the MHD and long wavelength

( ) Hall

MHD regimes. The left circularly polarised (ion cyclotron wave) component, on the other

hand, damps exponentially. It should be noted that this damping arises from resistive

dissipation, and as such should be distinguished from the kinetic ion cyclotron damping

arising from wave-particle interactions.

) Hall

MHD regimes. The left circularly polarised (ion cyclotron wave) component, on the other

hand, damps exponentially. It should be noted that this damping arises from resistive

dissipation, and as such should be distinguished from the kinetic ion cyclotron damping

arising from wave-particle interactions.

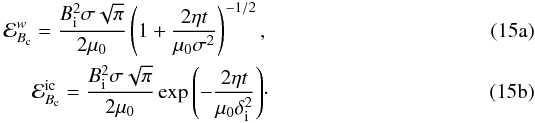

We may, again, calculate the energy associated with each solution (14b), using (11), where we still only obtain transverse perturbations, and hence

B1·B0

still makes no contribution to the energy. In this limit, we obtain an expression for the

energy associated with the individual whistler and i.c. wave branches:  Thus,

for waves in the

Thus,

for waves in the  regime, we no longer see the

initial transient phase seen previously in (12), and for long timescales the algebraically-damped whistler contribution to

the wave energy is dominant over the exponentially-damped contribution from the ion

cyclotron wave.

regime, we no longer see the

initial transient phase seen previously in (12), and for long timescales the algebraically-damped whistler contribution to

the wave energy is dominant over the exponentially-damped contribution from the ion

cyclotron wave.

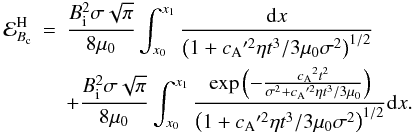

2.3. Phase-mixing and damping in a non-uniform plasma

By now allowing the equilibrium plasma density to vary in a direction perpendicular to

both the direction of the equilibrium field (y) and the direction of

initial perturbation (z), we can investigate what effect the Hall term

has on the dissipation rate in a non-uniform plasma. When the gradients in the

x-direction are sufficiently large, and the effects of viscosity are

negligible, the linearised Alfvén wave equation in the MHD limit takes the form (Hood et al. 2002):  (16)The

variation in Alfvén speed

(16)The

variation in Alfvén speed  causes steep gradients to build up in the direction of the inhomogeneity which, in turn,

significantly enhances resistive damping in the regions where the inhomogeneity is

greatest. Hood et al. (2002) used a multiple

time-scale analysis to derive from Eq. (16) a one-dimensional diffusion equation whose solutions can be expressed in terms

of the Alfvén speed gradient

cA′(x) = dcA(x) / dx.

For the case of the initially Gaussian pulse defined by Eq. (6), the forward-propagating solution takes the form:

causes steep gradients to build up in the direction of the inhomogeneity which, in turn,

significantly enhances resistive damping in the regions where the inhomogeneity is

greatest. Hood et al. (2002) used a multiple

time-scale analysis to derive from Eq. (16) a one-dimensional diffusion equation whose solutions can be expressed in terms

of the Alfvén speed gradient

cA′(x) = dcA(x) / dx.

For the case of the initially Gaussian pulse defined by Eq. (6), the forward-propagating solution takes the form: ![\begin{equation} B_z=\frac{B_{\rm i}}{2\sqrt{1+\ca'^2\eta t^3/3\muo\sigma^2}}\exp{\left(-\frac{\left(y-\ca t\right)^2 }{2\left[\sigma^2+\ca'^2\eta t^3/3\muo\right] }\right) }\cdot \label{eq:Hood1} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/01/aa15479-10/aa15479-10-eq74.png) (17)We can evaluate the

perturbed magnetic field energy per unit length in the z-direction

(17)We can evaluate the

perturbed magnetic field energy per unit length in the z-direction

for this case

by integrating

for this case

by integrating  over a finite

distance

x0 < x < x1

in the x-direction and from minus to plus infinity in the

y-direction, taking into account the presence of both forward- and

backward-propagating pulses. The y-integration can be performed

analytically, yielding:

over a finite

distance

x0 < x < x1

in the x-direction and from minus to plus infinity in the

y-direction, taking into account the presence of both forward- and

backward-propagating pulses. The y-integration can be performed

analytically, yielding:  (18)The

integrals in this expression can be readily evaluated numerically, to allow comparison

with our numerical simulations in the next section.

(18)The

integrals in this expression can be readily evaluated numerically, to allow comparison

with our numerical simulations in the next section.

3. Simulation results

The system was modelled numerically using a two dimensional version of a Lagrangian remap

scheme (LareXd), described by Arber et al. (2001),

which includes an optional Hall physics package to incorporate the Hall term into the

standard MHD system of equations, seen here in normalised dimensionless form:

![\begin{eqnarray*} &&\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t}+\dive{\left(\rho{\vec{v}} \right) }=0, \\ &&\rho\left( \frac{\partial {\vec{v}}}{\partial t}+\left( {\vec{v}}\cdot\boldnabla\right){\vec{v}} \right)= \left(\curl{\vec{B}}\right)\times{\vec{B}}-\grad{p}, \\ &&\frac{\partial {\vec{B}}}{\partial t}=\curl{\left( {\vec{v}}\times{\vec{B}}\right) }-\curl{\left(\eta\curl{\vec{B}} \right) } -\lambda_{\rm i}\curl{\left[\frac{1}{\rho}\left(\curl{\vec{B}}\times{\vec{B}} \right) \right] }, \\ &&\rho\left( \frac{\partial\epsilon}{\partial t}+\left( {\vec{v}}\cdot{\boldnabla}\right)\epsilon\right) =-p\dive{\vec{v}}+\eta j^2, \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/01/aa15479-10/aa15479-10-eq79.png) for

dimensionless mass density ρ, pressure p, magnetic field

strength B, fluid

velocity v, internal energy density ϵ,

resistivity η (the reciprocal of the Lundquist number) and ion skin depth

λi( = δi / l0).

for

dimensionless mass density ρ, pressure p, magnetic field

strength B, fluid

velocity v, internal energy density ϵ,

resistivity η (the reciprocal of the Lundquist number) and ion skin depth

λi( = δi / l0).

In Sect. 1, two particular regimes were identified where collisional models, such as this, may be more appropriate to describe the plasma behaviour than collisionless treatments. Normalising temperatures (T0) and densities (n0) using flaring coronal values (T0 ≈ 2 × 106 K and n0 ≈ 1016 m-3) or upper chromospheric values (T0 ≈ 2 × 104 K and n0 ≈ 2 × 1016 m-3) places the simulations firmly within these regimes. Specifying a low plasma beta (β = 0.01) in the simulations fixes the normalising magnetic field strengths to B0 ≈ 118 G in the flaring corona, or B0 ≈ 17 G in the upper chromosphere. This also determines the effective size of several fundamental plasma parameters, outlined for these normalising values in Table 1.

Approximate lengthscales.

The parameter λi (which controls the effect of the Hall term in

our simulations) was initially set equal to 0.0072. Using this value

of λi, together with the ion skin depths listed in Table 1, implies a normalising lengthscale

l0 = 0.3 km in the flaring corona, and

l0 = 0.2 km in the chromosphere. Given that the mean square

wavenumber for a Gaussian pulse of width σ can be found using

⟨ k2 ⟩ = 1 / σ2, a choice of

width σ = 0.1 places the simulations firmly within the long wavelength

regime (discussed in Sect. 2.1), as

. By relating simulated perturbation

frequencies (ω) to the perturbation size (by assuming

ω ~ kcA), our

choices for λi and σ perturb the simulations

with frequencies which have begun to approach the ion cyclotron frequency

(ω / Ωi ~ kδi ~ λi / σ ~ 0.07).

. By relating simulated perturbation

frequencies (ω) to the perturbation size (by assuming

ω ~ kcA), our

choices for λi and σ perturb the simulations

with frequencies which have begun to approach the ion cyclotron frequency

(ω / Ωi ~ kδi ~ λi / σ ~ 0.07).

As pointed out by Craig & Litvinenko (2002), the resistivity could be as much as a factor of 106 higher than the classical Spitzer value in the flaring corona. Using this enhancement factor and the normalisation described above for flaring conditions, we find η = 0.0005. Note that using the same value for η and the chromospheric normalisation, the enhancement of the resistivity as compared to the Spitzer value, is less than 102. An enhancement in the resistivity implies a corresponding reduction of the mean free paths quoted in Table 1. These reduced mean free paths are then much smaller than the typical wavelengths of the modes under consideration, so that Hall MHD is an appropriate model to use.

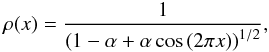

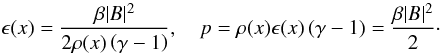

In order to study phase-mixing, we allow the equilibrium density to vary

along x, with the form:  (19)chosen for constant density

at the edges, ρ(0) = ρ(1) = 1, and a central increase in

density controlled by a steepness parameter, α. We also vary the specific

internal energy density of the system, ϵ, allowing us to define a constant

plasma pressure in terms of the plasma beta, β( = 0.01), and the magnetic

pressure, as:

(19)chosen for constant density

at the edges, ρ(0) = ρ(1) = 1, and a central increase in

density controlled by a steepness parameter, α. We also vary the specific

internal energy density of the system, ϵ, allowing us to define a constant

plasma pressure in terms of the plasma beta, β( = 0.01), and the magnetic

pressure, as:

We set up a constant

equilibrium field to reflect the analytical setup, with

B0( = [ B0x,B0y,B0z ] ) = [ 0,1,0 ] ,

which we perturb in the form outlined by Eq. (6). As our analytical work is based on a linearised system of equations, we fix

the pulse amplitude, Bi( = 0.0005) to be small enough that we

minimise non-linear effects. A 2000 × 2000 grid was used to fully resolve the effects of a

density gradient in x and potential whistler/i.c. effects

in y. As the density and energy density profiles are symmetric, periodic

boundary conditions are used in x, whilst the y boundaries

are left open, and the simulation terminated before the pulse reaches the boundaries. The

range of the numerical box (set, for the

We set up a constant

equilibrium field to reflect the analytical setup, with

B0( = [ B0x,B0y,B0z ] ) = [ 0,1,0 ] ,

which we perturb in the form outlined by Eq. (6). As our analytical work is based on a linearised system of equations, we fix

the pulse amplitude, Bi( = 0.0005) to be small enough that we

minimise non-linear effects. A 2000 × 2000 grid was used to fully resolve the effects of a

density gradient in x and potential whistler/i.c. effects

in y. As the density and energy density profiles are symmetric, periodic

boundary conditions are used in x, whilst the y boundaries

are left open, and the simulation terminated before the pulse reaches the boundaries. The

range of the numerical box (set, for the  simulations, at

− 10 ≤ y ≤ 10, 0 ≤ x ≤ 1) has a large range

in y, in anticipation of the pulse propagation.

simulations, at

− 10 ≤ y ≤ 10, 0 ≤ x ≤ 1) has a large range

in y, in anticipation of the pulse propagation.

Our initial investigation sought to recover, using Lare2d, the behaviour of the pulse and its evolution along the equilibrium field, in the long wavelength Hall MHD regime (expressed in Eq. (10)). For this investigation, selecting a steepness factor of α = 0 in our equilibrium density expression (Eq. (19)) provided the required uniform equilibrium density and uniform internal energy in the simulations. We found that the evolution of the pulse in the numerical scheme exactly matched the equivalent analytical expression (Eq. (10)), both in the MHD and long-wavelength Hall MHD (λi = 0.0072) limits.

Density enhancement values.

Moving to the non-uniform equilibrium density simulations, we then selected a range of specific equilibrium density enhancements through the steepness parameter α according to Eq. (19). The specific values of α chosen, and the corresponding density enhancements are listed in Table 2.

As discussed previously, Hood et al. (2002) obtained an expression describing the evolution of a pulse as it undergoes phase mixing in the MHD limit (Eq. (17)). We sought to test the validity of this expression for a range of equilibrium density gradients using Lare2d, by tracking the height and location of the peak of the pulse as it travelled along the equilibrium field, and comparing this with the pulse amplitude damping rate found by Hood et al. (2002). We found that the MHD simulations with large equilibrium density increases displayed good agreement with the proposed damping rate, but this agreement was lessened by reducing the equilibrium density enhancement. Furthermore, we repeated the simulations for the long wavelength Hall MHD regime, again finding that the amplitude evolution of the pulse was in agreement with the expression proposed by Hood et al. (2002), but only in the cases where the density enhancement was sufficiently large. These results are summarised in Fig. 1.

|

Fig. 1 Comparison of predicted amplitude fall-off for an analytical treatment of MHD phase-mixing (Eq. (17) – solid curve), with tracked pulse peak of Lare2d simulations. Displayed are the results of the MHD (crosses) and long wavelength Hall MHD (diamonds) simulations for three different density gradients (for corresponding density enhancements, see Table 2). |

|

Fig. 2 Temporal evolution of magnetic energy perturbation associated with initially Gaussian pulse, computed analytically for cases with uniform equilibrium density using Eq. (11) (stars), and strong equilibrium density gradient using Eq. (18) (dotted curve). The solid and dashed curves show the corresponding numerical results, obtained using Lare2d. |

Having studied the behaviour of the perturbed magnetic energy evolution in the uniform and steep density gradient limits using MHD simulations, we then investigated the energy response for a variety of different density gradients, and at different skin depths. For clarity, we also included the perturbed internal energy evolution of the pulse. Our first set of results compare the evolution of the pulse in MHD, with that of the λi = 0.0072 simulations, corresponding to the long wavelength Hall MHD regime, discussed in Sect. 2.1. These results are seen in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 clearly displays differences between the MHD and Hall MHD cases, for density gradients which are neither uniform nor very steep. To gain insight into the reasons for these differences, we have also tracked the evolution of the pulse profile in the x-direction as it travels at the Alfvén speed of the steepest density region. In the Hall MHD cases, we observe consistently smaller amplitude gradients. As an example of this, Fig. 4 shows snapshots of MHD and Hall MHD pulse profiles in simulations with α = 5 / 18. One might have expected the dispersive effects of the Hall term to induce a cascade into short wavelengths, which could in principle invalidate our neglect of kinetic effects. However, Fig. 4 shows that the opposite effect occurs: the Hall term actually reduces the gradients resulting from phase mixing.

We have demonstrated analytically that the plasma response dramatically differs in the

short wavelength ( ) Hall MHD limit, from that of the

MHD and long wavelength Hall MHD limits (Sect. 2). Our

final investigation sought to begin to bring out the behaviour of this limit by increasing

λi by a factor of 10. In doing so, we also reduce the

associated enhancement factor in resistivity required to justify setting

η = 0.0005 in the code. The enhancement factor is reduced to 105

for the flaring corona, whilst for the upper chromosphere the effective resistivity is less

than an order of magnitude larger than the equivalent Spitzer value, using the values

outlined earlier in Sect. 3. In these simulations, we

also increased the size of the numerical box (to − 30 ≤ y ≤ 30,

0 ≤ x ≤ 1, accounting for larger dispersive effects and the faster

whistler wave component) and the number of gridpoints (now at 6000 × 2000, maintaining the

same resolution). The perturbed frequencies in these simulations are now a large fraction of

the ion cyclotron frequency

(ω / Ωi ~ λi/σ ~ 0.7).

Figure 5 compares the response of the perturbed

magnetic and internal energies in simulations of a Hall MHD plasma with

λi = 0.072, with that of an MHD plasma, for three density

gradient cases which are neither uniform, nor dramatically varying. It is clear that in this

Hall MHD regime, there is a strong reduction in the damping rate compared to the MHD limit.

) Hall MHD limit, from that of the

MHD and long wavelength Hall MHD limits (Sect. 2). Our

final investigation sought to begin to bring out the behaviour of this limit by increasing

λi by a factor of 10. In doing so, we also reduce the

associated enhancement factor in resistivity required to justify setting

η = 0.0005 in the code. The enhancement factor is reduced to 105

for the flaring corona, whilst for the upper chromosphere the effective resistivity is less

than an order of magnitude larger than the equivalent Spitzer value, using the values

outlined earlier in Sect. 3. In these simulations, we

also increased the size of the numerical box (to − 30 ≤ y ≤ 30,

0 ≤ x ≤ 1, accounting for larger dispersive effects and the faster

whistler wave component) and the number of gridpoints (now at 6000 × 2000, maintaining the

same resolution). The perturbed frequencies in these simulations are now a large fraction of

the ion cyclotron frequency

(ω / Ωi ~ λi/σ ~ 0.7).

Figure 5 compares the response of the perturbed

magnetic and internal energies in simulations of a Hall MHD plasma with

λi = 0.072, with that of an MHD plasma, for three density

gradient cases which are neither uniform, nor dramatically varying. It is clear that in this

Hall MHD regime, there is a strong reduction in the damping rate compared to the MHD limit.

|

Fig. 3 Evolution of field perturbation energy in MHD (solid curve) and λi = 0.0072 Hall MHD (dashed curve) simulations for six values of density steepness parameter α. The internal energy is also plotted for the MHD (dot-dash curve) and λi = 0.0072 Hall MHD (dotted curve) simulations. |

4. Discussion and conclusions

The behaviour demonstrated by the analysis of a uniform plasma in the long wavelength Hall MHD regime (Sect. 2.1) was fully recovered by the Lare2d simulations. Both the simulated pulse evolution and its associated magnetic energy are indistinguishable from the expressions derived analytically (Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) respectively). The simulations show that the MHD results remain linearly polarised, whilst the long wavelength Hall MHD pulse becomes circularly polarised. However, both the simulations and the analytical results tell us that this has no impact on the magnetic energy associated with the pulse, which damps at the same rate in both regimes.

Considering now the results of the investigation concerning a non-uniform equilibrium

density, Fig. 1 shows that the amplitude damping rate

described by Hood et al. (2002) is well matched to

the rate of damping of the peak of an MHD pulse when the gradient in Alfvén speed is

sufficiently steep. Whilst not a particularly surprising result, as the strong phase mixing

limit required for Eq. (16) to be valid

applies in this case, it is somewhat more surprising to find for sufficiently steep Alfvén

speed gradients, that the long wavelength Hall MHD regime also conforms to this amplitude

damping rate. For shallower gradients in Alfvén speed, Fig. 1 also demonstrates that this damping rate quickly becomes inappropriate for the

Hall MHD simulations, whilst giving

better agreement with the MHD evolution of the peak of the pulse. This is partly due to the

fact that in the Hall regime, the pulse is no longer linearly polarised, quickly losing

amplitude to the other field components. The Hall regime is also subject to significant

dispersive effects, which reduce the amplitude of the pulse as it spreads along the

equilibrium field. However, for sufficiently steep density gradients, phase-mixing becomes

the dominant cause of amplitude dissipation.

Hall MHD simulations, whilst giving

better agreement with the MHD evolution of the peak of the pulse. This is partly due to the

fact that in the Hall regime, the pulse is no longer linearly polarised, quickly losing

amplitude to the other field components. The Hall regime is also subject to significant

dispersive effects, which reduce the amplitude of the pulse as it spreads along the

equilibrium field. However, for sufficiently steep density gradients, phase-mixing becomes

the dominant cause of amplitude dissipation.

By comparing the energy evolution associated with our numerical simulations of an MHD pulse to that found by numerically integrating an expression for the pulse evolution given by Hood et al. (2002) in Fig. 2, we see that, apart from a slight initial delay, the two results appear closely matched. The reason for the difference between the two is simply due to the treatments used. The linearised Alfvén wave (Eq. (16)) used in the treatments of Heyvaerts & Priest (1983) and Hood et al. (2002) retains only the x-derivatives, on the basis that derivatives along the field are small compared to those across it. However, in our simulations, the (initially uniform) pulse propagates a finite distance in which the y-derivative causes resistive damping along the equilibrium field. This continues until the gradients in x build up sufficiently to allow phase-mixing to become the dominant damping mechanism. The brief initial period of longitudinal damping is not included in the treatment of Hood et al. (2002), resulting in the discrepancies in behaviour seen between the energy evolution of the two non-uniform scenarios shown in Fig. 2.

Our final investigation sought to compare the response of the magnetic and internal energies associated with the pulse for different equilibrium density gradients and at different skin-depths. Figure 3 shows that for shallow density gradients, both MHD and long wavelength Hall MHD simulations display similar behaviour to that seen in the uniform case. For the steepest density gradients considered, again the long wavelength Hall MHD and MHD simulations exhibit similar behaviour, suggesting that MHD phase-mixing dominates the energy evolution (see Fig. 2). However, we see significant departures from the MHD behaviour of both perturbed magnetic and internal energies associated with the long wavelength Hall MHD regime, in the cases where the density is neither uniform nor sharply varying. In these cases, the inclusion of the Hall term causes the damping rate of perturbed magnetic energy to be reduced. Consequently there is a slower increase in the internal energy of the pulse than that seen in MHD: phase-mixing of the plasma causes less rapid plasma heating in the Hall MHD regime than in the MHD regime.

Evidence to support this can be seen in Fig. 4, where we plot a slice (in x) through pulse amplitude at the location (along y) of maximum phase-mixing, both for the λi = 0.0072 and MHD simulations. The figure clearly demonstrates that in the Hall case, the gradients in x are smaller than those in the MHD case. The whistler component of the Hall MHD pulse displays highly dispersive behaviour, which increases with skin depth. This dispersion spreads the pulse envelope along the equilibrium field as it travels, introducing higher wavenumbers into the pulse but only in the equilibrium field direction. In the density gradient direction, the group dispersion of the wave has the effect of reducing the damping rate by making amplitude gradients across the field (in x) smaller, reducing the efficiency of phase-mixing and its damping of the magnetic energy of the pulse.

This behaviour is also seen in the higher skin depth Hall MHD simulations. In the λi = 0.072 simulation results, seen in Fig. 5, there is now a very significant reduction in the damping rate of the magnetic energy, even in the steep density gradient case, which, in the long wavelength Hall MHD regime has begun to converge to the MHD results. As the skin depth is increased, the equilibrium density gradient must also be increased in order to recover a rate of energy dissipation comparable to those seen in the long wavelength Hall MHD and MHD limits.

|

Fig. 4 Comparison of two snapshots of slices (in x) through the pulse amplitude, at location (in y) of maximum phase-mixing. Snapshots shown are for long wavelength Hall MHD (solid) and MHD (dashed) cases, taken at the same time, for an identical initial pulse and with density steepness α = 5 / 18. |

|

Fig. 5 Evolution of field perturbation energy in MHD (solid curve) and λi = 0.072 Hall MHD (stars) simulations for three intermediate values of density gradient parameter α. Also plotted is the internal energy for the MHD (dot-dash curve) and λi = 0.072 Hall MHD (crosses) simulations. |

In summary, we have described analytically the propagation of an initially Gaussian field perturbation along a uniform equilibrium field in the presence of resistivity, and the evolution of magnetic energy associated with this perturbation. While the evolution of the perturbation differs in the MHD, long wavelength and short wavelength Hall MHD regimes, the energy evolution is the same in the MHD and long wavelength Hall MHD cases. In a non-uniform equilibrium plasma, our simulations show that the damping rate for the energy associated with the pulse in Hall MHD is significantly reduced when the Alfvén speed variation is neither uniform nor sharply varying, compared to that of an MHD treatment as the Hall term actually reduces the gradients resulting from phase-mixing. Moreover, as the ion skin depth is increased, the density gradient needed for MHD phase-mixing to dominate the evolution of the pulse (the “strong phase-mixing limit”) must also increase.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, under grant EP/G003955 and a CASE studentship, and by the European Communities under the contract of Association between EURATOM and CCFE. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. We thank P. J. Cargill & T. Neukirch (University of St. Andrews) for helpful discussions. I.D.M. acknowledges support of a Royal Society University Research Fellowship.

References

- Abramowitz, M., & Stegun, I. A. 1964, Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (New York: Dover) [Google Scholar]

- Arber, T. D., Longbottom, A. W., Gerrard, C. L., & Milne, A. M. 2001, J. Comput. Phys., 171, 151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bian, N., & Kontar, E. 2010, A&A, submitted [arXiv:1006.2729] [Google Scholar]

- Birn, J., & Priest, E. 2007, Reconnection of Magnetic Fields (New York: Cambridge University Press), 94 [Google Scholar]

- Birn, J., Drake, J. F., Shay, M. A., et al. 2001, J. Geophys. Res., 106, 3715 [Google Scholar]

- Botha, G. J. J., Arber, T. D., Nakariakov, V. M., & Keenan, F. P. 2000, A&A, 363, 1186 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, I. J. D., & Litvinenko, Y. E. 2002, ApJ, 570, 387 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, I. J. D., Litvinenko, Y. E., & Senanayake, T. 2005, A&A, 433, 1139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I. 2009, Space Sci. Rev., 149, 65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I., Hood, A. W., Ireland, J., & Arber, T. D. 1999, A&A, 346, 641 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I., Hood, A. W., & Arber, T. D. 2000, A&A, 354, 334 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Génot, V., Louarn, P., & Mottez, F. 2004, Ann. Geophys., 22, 2081 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B., McClements, K. G., Fletcher, L., & Thyagaraja, A. 2003, Sol. Phys., 214, 339 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaerts, J., & Priest, E. R. 1983, A&A, 117, 220 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, A. W., Ireland, J., & Priest, E. R. 1997, A&A, 318, 957 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, A. W., Brooks, S. J., & Wright, A. N. 2002, R. Soc. London Proc. Ser. A, 458, 2307 [Google Scholar]

- Marsch, E. 2006, Liv. Rev. Sol. Phys., 3, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Nakariakov, V. M., Roberts, B., & Murawski, K. 1997, Sol. Phys., 175, 93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ono, M., & Kulsrud, R. M. 1975, Phys. Fluids, 18, 1287 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, E. N. 1991, ApJ, 376, 355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sckopke, N., Paschmann, G., Brinca, A. L., Carlson, C. W., & Luehr, H. 1990, J. Geophys. Res., 95, 6337 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiklauri, D., & Haruki, T. 2008, Phys. Plasmas, 15, 112902 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiklauri, D., Sakai, J.-I., & Saito, S. 2005, A&A, 435, 1105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Comparison of predicted amplitude fall-off for an analytical treatment of MHD phase-mixing (Eq. (17) – solid curve), with tracked pulse peak of Lare2d simulations. Displayed are the results of the MHD (crosses) and long wavelength Hall MHD (diamonds) simulations for three different density gradients (for corresponding density enhancements, see Table 2). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Temporal evolution of magnetic energy perturbation associated with initially Gaussian pulse, computed analytically for cases with uniform equilibrium density using Eq. (11) (stars), and strong equilibrium density gradient using Eq. (18) (dotted curve). The solid and dashed curves show the corresponding numerical results, obtained using Lare2d. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Evolution of field perturbation energy in MHD (solid curve) and λi = 0.0072 Hall MHD (dashed curve) simulations for six values of density steepness parameter α. The internal energy is also plotted for the MHD (dot-dash curve) and λi = 0.0072 Hall MHD (dotted curve) simulations. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Comparison of two snapshots of slices (in x) through the pulse amplitude, at location (in y) of maximum phase-mixing. Snapshots shown are for long wavelength Hall MHD (solid) and MHD (dashed) cases, taken at the same time, for an identical initial pulse and with density steepness α = 5 / 18. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Evolution of field perturbation energy in MHD (solid curve) and λi = 0.072 Hall MHD (stars) simulations for three intermediate values of density gradient parameter α. Also plotted is the internal energy for the MHD (dot-dash curve) and λi = 0.072 Hall MHD (crosses) simulations. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.