| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A60 | |

| Number of page(s) | 6 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014486 | |

| Published online | 21 October 2010 | |

Planetary transit timing variations induced by stellar binarity

The light travel time effect

M. Montalto1,2

1 - Max-Planck-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr., 85741 Garching b. Muenchen, Germany

2 -

Universitaetssternwarte Muenchen, Scheiner Str. 1, 81679 Muenchen, Germany

Received 23 March 2010 / Accepted 15 June 2010

Abstract

Context. Since the discovery of the first transiting

extrasolar planet, transit timing has been recognized as a powerful

method to discover and characterize additional planets in these

systems. However, the gravitational influence of additional

planets is not the only expected source of transit timing variations.

Aims. In this work, we derive the expected detection frequency

of stellar companions of hot-jupiter transiting planets host-stars,

detectable by means of transit timing analysis. Since roughly half of

the stars in the solar neighborhood belong to binary or multiple

stellar systems, the same fraction of binary systems may be expected to

be present among transiting planet-host stars, unless planet formation

is significantly influenced by the presence of a stellar companion.

Transit searches are less affected by the selection biases against

long-period binaries that plague radial velocity surveys.

Methods. We considered the frequency and the period, mass ratio

and eccentricity distributions of known binary systems in the solar

neighborhood, and estimated the fraction of transiting planet-hosts

expected to show detectable transit timing variations due to the light

travel time effect in a binary stellar system, in function of the

time since the discovery of the planet.

Results. If the frequency of binaries among hot-jupiter planet

host stars is the same as determined in the solar neighborhood, after

5 years since the discovery of a sample of transiting planets ![]()

![]()

![]() of them have a probability

of them have a probability ![]() to present transit timing variations >50 s induced by stellar binarity, and

to present transit timing variations >50 s induced by stellar binarity, and ![]()

![]()

![]() after 10 years, if the planetary and binary orbits are

coplanar. Considering the case of random inclinations the probabilities

are

after 10 years, if the planetary and binary orbits are

coplanar. Considering the case of random inclinations the probabilities

are ![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]() after 5 and 10 years respectively. Our estimates can be

considered conservative lower limits, since we have taken into account

only binaries with periods P>5

after 5 and 10 years respectively. Our estimates can be

considered conservative lower limits, since we have taken into account

only binaries with periods P>5 ![]() 103 days (

103 days (![]() AU).

Our simulations indicate that transit timing variations due to the

light travel time effect will allow us to discover stellar companions

up to maximum separations equal to

AU).

Our simulations indicate that transit timing variations due to the

light travel time effect will allow us to discover stellar companions

up to maximum separations equal to ![]() AU after 5 years since the discovery of the planet (

AU after 5 years since the discovery of the planet (![]() AU after 10 years).

AU after 10 years).

Conclusions. Comparing the results of the observations with the

above predictions allows to understand if stellar companions at

critical separations (<100 AU) are favoring or hindering the

formation of hot-jupiter planets. Comparing the results of transit

timing detections with those obtained by other complementary methods

results in a more complete determination of stellar multiplicity around

transiting planet-host stars. Moreover, transit timing analysis allows

us to probe stellar multiplicity at critical separations

(<100 AU) around stars located in different regions of the

Galaxy, and not just in the solar neighborhood.

Key words: time - ephemerides - occultations - binaries: general

1 Introduction

The frequency of binary stars and multiple stellar systems around solar-like stars in the solar neighborhood has been extensively studied in the past. Duquennoy & Mayor (1991), from a sample of 164 primary G-dwarf stars analyzed during almost 13 yr with the CORAVEL spectrograph, obtained that the ratios of single:double:triple:quadruple systems are 51:40:7:2 respectively. This fraction of binaries should be present also in a sample of planet host stars if planets do form in any kind of binary systems and there are no selection biases applied to define the sample of stars where the planets are searched for.

From a theoretical point of view the problem of the formation

of giant planets in close binary systems is still largely debated.

Truncation and heating of circumstellar protoplanetary disks are

expected to occur in close binary systems (Artymowics & Lubow 1994; Nelson 2000). However there is no general consensus on which consequences these processes have on planet formation. Nelson (2000)

showed that the formation of giant planets is unlikely in equal mass binaries with semi-major

axis ![]() AU, both by means of the disk instability (Boss 1997) and the core accretion mechanisms (Pollack et al. 1996).

On the contrary Boss (2006), showed that in the context of the disk

instability scenario, the presence of a close-by stellar companion may

in fact trigger clumps formation leading to giant planets. Along the

same lines Duchêne (2010) suggested that in tight binaries (a<100 AU)

massive planets are formed by disk instability at the same rate as less

massive planets in wider binaries and single stars.

AU, both by means of the disk instability (Boss 1997) and the core accretion mechanisms (Pollack et al. 1996).

On the contrary Boss (2006), showed that in the context of the disk

instability scenario, the presence of a close-by stellar companion may

in fact trigger clumps formation leading to giant planets. Along the

same lines Duchêne (2010) suggested that in tight binaries (a<100 AU)

massive planets are formed by disk instability at the same rate as less

massive planets in wider binaries and single stars.

According to Marzari et al. (2005),

independently from the planet formation mechanism, tidal perturbations

of the companion star influence both the onset of instability and the

following chaotic evolution of protoplanetary disks. In particular

several studies have pointed out that the gravitational influence of

stellar companions on the dynamics of planetary systems becomes

significant at separations ![]() AU (e.g. Pfhal & Muterspaugh 2006; Desidera & Barbieri 2007; Duchêne 2010).

Despite that, four planetary systems have been discovered in binaries

with separations around 20 AU: Gamma Cephei (Hatzes

et al. 2003), Gliese 86 (Queloz et al. 2000; Els et al. 2001), HD 41004 (Santos et al. 2002), and HD 196885 (Correia et al. 2008).

These observational results are clearly challenging our current

knowledge of planet formation and evolution in binary systems.

AU (e.g. Pfhal & Muterspaugh 2006; Desidera & Barbieri 2007; Duchêne 2010).

Despite that, four planetary systems have been discovered in binaries

with separations around 20 AU: Gamma Cephei (Hatzes

et al. 2003), Gliese 86 (Queloz et al. 2000; Els et al. 2001), HD 41004 (Santos et al. 2002), and HD 196885 (Correia et al. 2008).

These observational results are clearly challenging our current

knowledge of planet formation and evolution in binary systems.

Several imaging surveys have successfully identified stellar companions to planet-host stars (e.g. Patience et al. 2002; Luhman & Jayawardhana 2002; Chauvin et al. 2006; Mugrauer et al. 2007; Eggenberger et al. 2007; Eggenberger & Udry 2007).

At present, giant planets around wide binary systems appear as

frequent as planets around single stars (Bonavita & Desidera 2007),

suggesting that wide binaries are not significantly altering planet

formation processes. However, there is a marginal statistical evidence

that binaries with separations smaller than 100 AU may have a

lower frequency of planetary systems than around single stars.

Eggenberger et al. (2008)

estimated a difference in the binary frequency between carefully

selected samples of non planet-host and planet-host stars ranging

between ![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]() ,

considering binaries with semi-major axis between 35 AU and

250 AU, further pointing out that this difference seems mostly

evident for binaries with a<100 AU.

These results are obtained using samples of stars hosting radial

velocity discovered planets, for the obvious reason that Doppler

spectroscopy has been so far the most successful planet detection

method, providing then the largest sample of planets from which

statistical conclusions can be drawn. Nevertheless, planets discovered

with this technique are known to be adversely selected against close

binaries. Doppler spectroscopy is complicated by light contamination of

stellar companions, and blending of spectral lines. This implies that

radial velocity surveys typically exclude known moderately and close

binaries from their target lists. As a consequence the

occurrence of planetary systems in binaries, and in particular at

critical separations (

,

considering binaries with semi-major axis between 35 AU and

250 AU, further pointing out that this difference seems mostly

evident for binaries with a<100 AU.

These results are obtained using samples of stars hosting radial

velocity discovered planets, for the obvious reason that Doppler

spectroscopy has been so far the most successful planet detection

method, providing then the largest sample of planets from which

statistical conclusions can be drawn. Nevertheless, planets discovered

with this technique are known to be adversely selected against close

binaries. Doppler spectroscopy is complicated by light contamination of

stellar companions, and blending of spectral lines. This implies that

radial velocity surveys typically exclude known moderately and close

binaries from their target lists. As a consequence the

occurrence of planetary systems in binaries, and in particular at

critical separations (![]() AU), is still poorly constrained by the observations.

While the use of a control sample of stars, proposed by Eggenberger et al. (2007, 2008),

is expected to mitigate the impact on the results given by the

bias against close binaries applied by radial velocity surveys, other

samples of planet-host stars and different techniques may be useful to

probe the frequency of planets in binary stellar systems.

AU), is still poorly constrained by the observations.

While the use of a control sample of stars, proposed by Eggenberger et al. (2007, 2008),

is expected to mitigate the impact on the results given by the

bias against close binaries applied by radial velocity surveys, other

samples of planet-host stars and different techniques may be useful to

probe the frequency of planets in binary stellar systems.

While radial velocity planet searches tend to exclude binaries from

their target lists, transit searches do not apply a priori

selection criteria against binaries. Transiting planets are routinely

searched among all stars, and then subjected to follow-up photometric

and spectroscopic analysis. Photometric analysis aims mainly at ruling

out grazing eclipsing binary stellar systems which manifest themselves

by means of markedly V-shaped eclipses, the presence of secondary

eclipses, color changes during the eclipses and light modulations with

the same periodicity of the transiting object. Spectroscopic analysis

is then used to further rule-out giant stars primaries and the more

complicated scenarios involving hierarchical triple systems with an

eclipsing binary stellar system, and blends with background eclipsing

binaries (Brown 2003).

However, these follow-up analysis do not eliminate planets in binary

stellar systems. Several transiting planets are already known members

of binaries (e.g. Daemgen et al. 2009),

and others have suspected close companions as indicated by the presence

of radial velocity and transit timing variations (Winn et al. 2010; Maxted et al. 2010; Queloz et al. 2010; Rabus et al. 2009). Moreover for transiting planets we have a firm constraint on the planetary orbital inclination (which is close to

![]() ). The Rossiter-McLaughlin effect (Rossiter 1924; McLaughlin 1924) can be used to probe the sky-projected angle

). The Rossiter-McLaughlin effect (Rossiter 1924; McLaughlin 1924) can be used to probe the sky-projected angle ![]() between the stellar rotation axis and the planet's orbital axis. By transforming the projected angle

between the stellar rotation axis and the planet's orbital axis. By transforming the projected angle ![]() into the the real spin-orbit angle

into the the real spin-orbit angle ![]() using a statistical approach and the entire sample of planets with Rossiter-McLaughlin measurements, Triaud et al. (2010) derived that most transiting planets have misaligned orbits (80

using a statistical approach and the entire sample of planets with Rossiter-McLaughlin measurements, Triaud et al. (2010) derived that most transiting planets have misaligned orbits (80![]() with

with

![]() ), and that the histogram of projected obliquities closely reproduces the theoretical distribution of

), and that the histogram of projected obliquities closely reproduces the theoretical distribution of ![]() using Kozai cycles and tidal friction (Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007).

Since type I and II migration are not able to explain the

present observations, the indication is that the Kozai mechanism

is the major responsible of the formation of hot-jupiter planets. In

this case, we should expect that most hot-jupiter planets

have stellar companions. The discovery of close stellar companions to

transiting planets systems

is then of primary importance, since it would constitute a strong proof

in favor of the Kozay cycles and tidal friction mechanism. Transiting

planets host stars then constitute an interesting sample of objects

where to look for additional distant companions. The presence of a

stellar companion around these stars can be inferred at least by means

of four independent and complementary techniques: transit timing

variations, radial velocity drifts, direct imaging and IR excess.

using Kozai cycles and tidal friction (Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007).

Since type I and II migration are not able to explain the

present observations, the indication is that the Kozai mechanism

is the major responsible of the formation of hot-jupiter planets. In

this case, we should expect that most hot-jupiter planets

have stellar companions. The discovery of close stellar companions to

transiting planets systems

is then of primary importance, since it would constitute a strong proof

in favor of the Kozay cycles and tidal friction mechanism. Transiting

planets host stars then constitute an interesting sample of objects

where to look for additional distant companions. The presence of a

stellar companion around these stars can be inferred at least by means

of four independent and complementary techniques: transit timing

variations, radial velocity drifts, direct imaging and IR excess.

Deriving the expected frequency of transiting planet host stars in binary stellar systems detectable by each one of the above mentioned techniques is then important, since comparing the results of the observations with the predictions we can better understand which influence close binary systems have on planet formation and evolution. If, for example, the existence of hot-jupiters is connected to the presence of close-by stellar companions, we should expect to derive a higher binary frequency around stars hosting these planets, with respect to the frequency of binaries observed in the solar neighborhood. If, on the contrary, the presence of close-by stellar companions strongly prevents the existence of planets, we should expect a lower frequency. In this paper we focus our attention on transit timing variations (TTVs) induced by stellar binarity. Future contributes will account for the other techniques.

In particular here we derive the expected frequency of transiting planets in binary systems

detectable by TTVs. We define the

![]() as the fraction of

transiting planets expected to show

detectable TTVs induced by stellar binarity over some fixed

timescales, when the only source of TTVs under consideration is the

light travel time effect in binary systems. The presence of an

additional stellar companion around a transiting planet-host star,

should induce TTVs even if we neglect perturbing effects, because of

the variable distance of

the host star with respect to the observer in the course of its orbital

revolution around the barycenter of the binary stellar system. This

motion induces TTVs affecting the observed period of the transiting

object, and consequently the ephemerides of the transits

(e.g. Irwin 1959).

as the fraction of

transiting planets expected to show

detectable TTVs induced by stellar binarity over some fixed

timescales, when the only source of TTVs under consideration is the

light travel time effect in binary systems. The presence of an

additional stellar companion around a transiting planet-host star,

should induce TTVs even if we neglect perturbing effects, because of

the variable distance of

the host star with respect to the observer in the course of its orbital

revolution around the barycenter of the binary stellar system. This

motion induces TTVs affecting the observed period of the transiting

object, and consequently the ephemerides of the transits

(e.g. Irwin 1959).

Transit timing allows detenction of close stellar companions around

more distant planet-host stars than direct imaging. Accurate transit

timing measurements are achievable also for planets discovered around

faint and distant planet-hosts, by means of a careful choice of the

telescope and the detector (e.g. Adams et al. 2010).

On the contrary, the distance of the planet-host constitutes a limit

for direct imaging detection of stellar companions. Using VLT/NACO, and

targeting solar type close-by stars (![]() pc), a companion with a mass of

pc), a companion with a mass of

![]() (then just at the limit of the brown dwarf regime) can be detected at the 3-

(then just at the limit of the brown dwarf regime) can be detected at the 3-![]() limit at a projected separation of 0.3 arcsec (e.g. Schnupp et al. 2010; Eggenberger et al. 2007),

which corresponds to 3 AU. If, however, the star is

located at a distance >333 pc, direct imaging can probe only

separations >100 AU. Then transit timing allows us to probe

stellar multiplicity at critical separations <100 AU

(as demonstrated in this work) around more distant samples of

transiting planet host-stars with respect to what can be done by direct

imaging, giving the opportunity to probe stellar multiplicity around

targets located in different regions of the Galaxy. Moreover, while

direct imaging is more efficient in detecting companions in face-on

orbits, transit timing

(and Doppler spectroscopy) is more efficient in the case of edge-on

systems.

limit at a projected separation of 0.3 arcsec (e.g. Schnupp et al. 2010; Eggenberger et al. 2007),

which corresponds to 3 AU. If, however, the star is

located at a distance >333 pc, direct imaging can probe only

separations >100 AU. Then transit timing allows us to probe

stellar multiplicity at critical separations <100 AU

(as demonstrated in this work) around more distant samples of

transiting planet host-stars with respect to what can be done by direct

imaging, giving the opportunity to probe stellar multiplicity around

targets located in different regions of the Galaxy. Moreover, while

direct imaging is more efficient in detecting companions in face-on

orbits, transit timing

(and Doppler spectroscopy) is more efficient in the case of edge-on

systems.

This paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, we review the known properties of binary stellar systems in the solar neighborhood; in Sect. 3, we discuss the light travel time effect of transiting planets in binaries; in Sect. 4, we describe the Monte Carlo simulations we did to constrain the frequency of transiting planet-host stars presenting detectable transit timing variations induced by binarity over some fixed timescales; in Sect. 5, we discuss the results of our analysis; in Sect. 6, we summarize and conclude.

2 Properties of multiple stellar systems

From their study of multiple stellar systems in the solar neighborhood, Duquennoy & Mayor (1991) derived the following properties for binary stellar systems with mass ratios q>0.1:

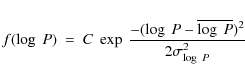

1) the orbital period distribution can be approximated by:

|

(1) |

where

2) binaries with periods P>1000 days (which is the range of periods in which we are interested, see below) have an observed eccentricity distribution which tends smoothly toward h(e)=2e;

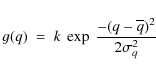

3) the mass-ratio ( q=m2/m1) distribution can be approximated by:

|

(2) |

where

In the following we will consider only binaries with periods P>5 ![]() 103 days.

This limit is due to the need to minimize perturbing effects, which

have been explicitely neglected in our analysis, as explained

in Sect. 3.

103 days.

This limit is due to the need to minimize perturbing effects, which

have been explicitely neglected in our analysis, as explained

in Sect. 3.

Using the period distribution of Duquennoy & Mayor (1991), we have that ![]() 68

68![]() of all binary systems are expected to have P>5

of all binary systems are expected to have P>5 ![]() 103 days and, considering that the frequency of binary stellar systems in the solar neighborhood is 40

103 days and, considering that the frequency of binary stellar systems in the solar neighborhood is 40![]() (as reported in Sect. 1, excluding multiple stellar systems), we have that the expected frequency of binaries in our period range is equal to

(as reported in Sect. 1, excluding multiple stellar systems), we have that the expected frequency of binaries in our period range is equal to

![]() .

.

The aim of the rest of this paper is to establish how many of these systems should appear as detectable transit timing sources over a timescale of at most 10 years since the discovery of the transiting planets around the primary stars of these systems.

3 The light travel time effect

In the following we consider the case of a planet orbiting the

primary star of a binary stellar system. This configuration is usually

called S-type orbit. We will also assume that the planet is revolving

much closer to its parent star than the companion star (

![]() where

where

![]() is the binary orbital period, and

is the binary orbital period, and

![]() is the planet orbital period). This is a reasonable assumption given the range of binary periods we are considering (

is the planet orbital period). This is a reasonable assumption given the range of binary periods we are considering (

![]()

![]() 103 days,

see above), and that most transiting planets are typically

hot-jupiters with a period of only a few days. Under this

assumption, and given also that our adopted observing window

(10 years) is smaller than the shortest period we considered,

the perturbing effects of the secondary star on the orbit of the

inner planet can be neglected

103 days,

see above), and that most transiting planets are typically

hot-jupiters with a period of only a few days. Under this

assumption, and given also that our adopted observing window

(10 years) is smaller than the shortest period we considered,

the perturbing effects of the secondary star on the orbit of the

inner planet can be neglected![]() .

The three body problem can be splitted in two independent two body

problems: the motion of the planet around the host star (which can

be reasonably assumed coincident with the barycenter of the planetary

system given that the mass of the planet is much smaller than the mass

of the star), and the motion of the host star around the barycenter of

the binary system. Even neglecting perturbing effects, we expect

transit timing variations to be present, due to the light travel

time effect, as described in Sect. 1. The transiting planet can be used as a precise clock unveiling the presence of the additional star in the system.

.

The three body problem can be splitted in two independent two body

problems: the motion of the planet around the host star (which can

be reasonably assumed coincident with the barycenter of the planetary

system given that the mass of the planet is much smaller than the mass

of the star), and the motion of the host star around the barycenter of

the binary system. Even neglecting perturbing effects, we expect

transit timing variations to be present, due to the light travel

time effect, as described in Sect. 1. The transiting planet can be used as a precise clock unveiling the presence of the additional star in the system.

We consider a reference system with the origin in the barycenter of the binary system. The Z axis is aligned along the line of sight, the X axis along the nodal line defined by the intersection between the binary orbital plane and the plane of the sky, and the Y axis consequently assuming a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system. The XY-plane is tangent to the celestial sphere.

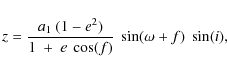

The distance (z) between the host star and the

barycenter of the binary system, projected along the observer line of

sight is given by (e.g. Kopal 1959):

|

(3) |

where the orbital elements are relative to the barycentric orbit of the host star. Using the equation of the center of mass a1=m2a/(m1+m2), the Kepler law and dividing by the speed of light (c), gives:

![\begin{displaymath}%

O(t)=\frac{(G)^{1/3}~P^{2/3}(1-e^2)~m_2~\sin(i)}{c~(2\pi)^{2/3}(m_1+m_2)^{2/3}}~\frac{\sin(\omega+f[t])}{1+e~\cos(f[t])},

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/img50.png)

|

(4) |

where f is the true anomaly, e is the eccentricity of the orbit, and i is the inclination with respect to the plane of the sky, m1 and m2 are the masses of the primary and of the secondary,

Equation (4) gives the time necessary to cover the distance

projected along the line of sight between the host star and the

barycenter of the binary system at the speed of light. We can also say

that Eq. (4) gives the difference between the observed ephemerides

of the transiting planet once including the light time effect and the

ephemerides obtained considering the intrinsic period of the planet![]() .

.

The rate of change over time of the observed planet period with respect

to the intrinsic planet period is given by the derivative of

Eq. (4) over time:

![\begin{displaymath}%

\epsilon(t) \!=\!\frac{(2\pi)^{1/3}}{c~P^{1/3}}~\frac{(G)^{...

...m_2)^{2/3}}\Big(\cos(\omega\!+\!f[t])\!+\!e~\cos(\omega)\Big).

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/img53.png)

|

(5) |

The procedure usually adopted by observers to determine the period of a transiting object is based on the determination of the time interval between two or more measured transits at an epoch t0. Then

| (6) |

Imposing that the

| (7) |

![\begin{figure}

\par\hspace*{-3mm}\includegraphics[width=7.9cm,clip]{14486fg1a.eps}\vspace*{3mm}

\includegraphics[width=7.6cm,clip]{14486fg1b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 1:

Upper figure, upper panel: the black solid curve represents the

difference between the observed transit ephemerides of the planet once

including the light time effect and the ephemerides obtained once

considering the intrinsic period of the planet

(Eq. (4), see text). The dotted line represents the

accumulation over time of the difference between the observed period of

the planet and its intrinsic period if the planet period is measured at

the epoch t0 coincident with the origin of the x-axis, and it is then assumed constant. Upper figure, lower panel: the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 1

(upper figure), we present an illustrative example. We consider a

binary system where the relevant orbital elements were fixed at the

median values derived by Duquennoy & Mayor (1991):

![]() = 172.865 years, e=0,

q=m2/m1=0.23,

= 172.865 years, e=0,

q=m2/m1=0.23, ![]() ,

,

![]() .

We assume that a planet is orbiting the primary star of the binary

system, and that the period of the planet was measured at the

epoch t0 (assumed coincident with the origin of the x-axis in Fig. 1).

After five years the transit timing variation is 46 s, and after

ten years it is 178 s, as shown in the inner plot of

Fig. 1. The binary we have considered is one of the typical binaries in the solar surrounding. We also observe that the

.

We assume that a planet is orbiting the primary star of the binary

system, and that the period of the planet was measured at the

epoch t0 (assumed coincident with the origin of the x-axis in Fig. 1).

After five years the transit timing variation is 46 s, and after

ten years it is 178 s, as shown in the inner plot of

Fig. 1. The binary we have considered is one of the typical binaries in the solar surrounding. We also observe that the ![]() diagram is in general not periodic as evident already from Fig. 1.

diagram is in general not periodic as evident already from Fig. 1.

4 Simulations

In this section we describe the orbital simulations we did to constrain

the expected frequency of transiting planet-host stars that should

present a detectable transit timing variation induced by stellar

binarity over a timescale of 5 years and 10 years since the

discovery of the planet around the primary star of the system. The

detectability threshold was fixed considering the results obtained by

transit timing searchers with ground based telescopes. Rabus

et al. (2009),

observing the planetary system TrES-1 with the IAC80 cm telescope

obtained mean precisions of 18.5 s, which is also in agreement

with the theoretical equation given by Doyle & Deeg (2004).

On the basis of that, and using several other literature results, they

were already able to claim the presence of a linear trend equivalent to

48 s (obtained from their best-fit parameter) over the period of

4.1 yr spanned by the entire sample of the observations. Winn

et al. (2009) measured two

transits of the giant planet WASP-4b with the Baade 6.5 m

telescope obtaining mid-transit times precisions of ![]() 6 s.

Typically it can be assumed that small or moderate groundbased

telescopes can reach precisions <20 s, while large telescope

may reach better than 10 s precision. Given these results we

considered that a TTV detection threshold equal to

6 s.

Typically it can be assumed that small or moderate groundbased

telescopes can reach precisions <20 s, while large telescope

may reach better than 10 s precision. Given these results we

considered that a TTV detection threshold equal to ![]() = 50 s can be reasonably applied in our analysis.

= 50 s can be reasonably applied in our analysis.

We randomly chose the period, mass ratio, and eccentricity of the

binary considering the probability distributions presented in

Sect. 2. The mass of the primary star was fixed at

![]() ,

since we are considering binarity among typical solar type stars. The

argument of the pericenter was instead randomly chosen using a uniform

probability distribution. The inclination was either fixed to

,

since we are considering binarity among typical solar type stars. The

argument of the pericenter was instead randomly chosen using a uniform

probability distribution. The inclination was either fixed to

![]() (to consider the case of coplanar orbits) or randomly chosen

using a uniform probability distribution. For each orbit (characterized by P, e, q,

(to consider the case of coplanar orbits) or randomly chosen

using a uniform probability distribution. For each orbit (characterized by P, e, q, ![]() , i) we numerically solved the disequation (7) in function of t0 (the epoch of the planetary period determination). We subdivided the period P

in 10 000 equal intervals of time and evaluated

disequation (7) at the extremes these intervals. Then we isolated

the intervals in which disequation (7) changed sign, and using the

secant method imposing a threshold for the convergence equal to

0.1 s we obtained the roots of the correspondent equation. Then we

determined the intervals

, i) we numerically solved the disequation (7) in function of t0 (the epoch of the planetary period determination). We subdivided the period P

in 10 000 equal intervals of time and evaluated

disequation (7) at the extremes these intervals. Then we isolated

the intervals in which disequation (7) changed sign, and using the

secant method imposing a threshold for the convergence equal to

0.1 s we obtained the roots of the correspondent equation. Then we

determined the intervals

![]() where

disequation (7) was satisfied. Summing up together these intervals

of time and dividing by the period of the binary gave the probability

to observe the requested transit timing variation for that fixed orbit

over the given timescale (

where

disequation (7) was satisfied. Summing up together these intervals

of time and dividing by the period of the binary gave the probability

to observe the requested transit timing variation for that fixed orbit

over the given timescale (

![]() either

5 yr or 10 yr in our simulations) assuming to determine the

period of the transiting planet in correspondence of a random orbital

phase of the binary. In such a way we assigned to each simulated

orbit a transit timing detection probability (

either

5 yr or 10 yr in our simulations) assuming to determine the

period of the transiting planet in correspondence of a random orbital

phase of the binary. In such a way we assigned to each simulated

orbit a transit timing detection probability (

![]() ). In Fig. 1 (lower figure), we show the graphical representation of disequation (7) in function of t0, the epoch of the planetary period determination, for the case of the orbit considered in Fig. 1 (upper figure), assuming a transit timing threshold

). In Fig. 1 (lower figure), we show the graphical representation of disequation (7) in function of t0, the epoch of the planetary period determination, for the case of the orbit considered in Fig. 1 (upper figure), assuming a transit timing threshold ![]() s,

and a timescale of 10 years. The horizontal black solid lines

denote the time intervals where disequation (7) is satisfied. We

performed 100 runs of 10 000 simulations each,

calculating the mean detection probabilities and their 1-

s,

and a timescale of 10 years. The horizontal black solid lines

denote the time intervals where disequation (7) is satisfied. We

performed 100 runs of 10 000 simulations each,

calculating the mean detection probabilities and their 1-![]() uncertainties, as reported in the next section.

uncertainties, as reported in the next section.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{14486fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/Timg65.png)

|

Figure 2:

Distributions of the detection probabilities (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Results

The final detection probability histograms are shown in Fig. 2, obtained from the entire sample of 106 simulated

orbits. While most orbits imply null detection probabilities over the

assumed timescales, in each one of the different situations we

considered, the histograms present a probability tail extended

toward large detection probabilities. The number of orbits having

![]() is equal to

is equal to ![]()

![]()

![]() after 5 years since the period determination (

after 5 years since the period determination (![]()

![]()

![]() after 10 years) for the case of coplanar orbits, and is equal to

after 10 years) for the case of coplanar orbits, and is equal to ![]()

![]()

![]() after 5 years (

after 5 years (![]()

![]()

![]() after 10 years) for the case of random inclinations. The fact that

the histograms are extended toward large probabilities is a consequence

of the period distribution and the adopted timescales. Orbits having

after 10 years) for the case of random inclinations. The fact that

the histograms are extended toward large probabilities is a consequence

of the period distribution and the adopted timescales. Orbits having

![]() have also

periods smaller than P<1.67

have also

periods smaller than P<1.67 ![]() 105

(considering a timescale of 10 years), which means that transit

timing can allow discovery of stellar companions up to separations

equal to

105

(considering a timescale of 10 years), which means that transit

timing can allow discovery of stellar companions up to separations

equal to ![]() AU after 10 years since the discovery of the planet (

AU after 10 years since the discovery of the planet (![]() AU after 5 years).

AU after 5 years).

Then, considering the observed frequency of binaries in the solar surrounding with periods P>5 ![]() 103 days (27

103 days (27![]() )

and the case of coplanar orbits, after 5 years since the discovery of a sample of transiting planets

)

and the case of coplanar orbits, after 5 years since the discovery of a sample of transiting planets ![]()

![]()

![]() transiting planet host-stars will have a probability

transiting planet host-stars will have a probability

![]() to present

detectable (>50 s) transit timing variations induced by stellar binarity, and

to present

detectable (>50 s) transit timing variations induced by stellar binarity, and ![]()

![]()

![]() after 10 years. Considering the case of random inclinations the expected frequencies (

after 10 years. Considering the case of random inclinations the expected frequencies (

![]() )

are

)

are ![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]() after 5 and 10 years respectively. These results are summarized in Table 1. Our estimates can be considered a conservative lower limit, since we have excluded binaries with periods P<5

after 5 and 10 years respectively. These results are summarized in Table 1. Our estimates can be considered a conservative lower limit, since we have excluded binaries with periods P<5 ![]() 103 days.

103 days.

Table 1:

Expected frequency (

![]() )

of binary stellar systems detectable by means of transit timing variations in function of the timescale (

)

of binary stellar systems detectable by means of transit timing variations in function of the timescale (![]() )

since the discovery of the planet, and of different assumptions on the inclination of the binary stellar systems.

)

since the discovery of the planet, and of different assumptions on the inclination of the binary stellar systems.

6 Conclusions

In this paper we have investigated how known transiting extrasolar planets can be used to constrain the frequency of multiple stellar systems among planet-host stars. The presence of a stellar companion in these systems is expected to induce transit timing variations of the transiting planets even once perturbing effects are neglected, due to the orbital revolution of the primary around the barycenter of the binary stellar system.

If the frequency of binaries among planet-host stars is the same as

determined in the solar neighborhood, after 5 years since the

discovery of a sample of transiting planets ![]()

![]()

![]() of them have a probability

of them have a probability ![]() to present a transit timing variations >50 s induced by stellar binarity, and 2.8

to present a transit timing variations >50 s induced by stellar binarity, and 2.8 ![]()

![]() after 10 years if the planetary and binary orbits are coplanar.

Considering the case of random inclinations the probabilities are

after 10 years if the planetary and binary orbits are coplanar.

Considering the case of random inclinations the probabilities are ![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]() after 5 and 10 years respectively. Our results have been obtained assuming a binary period P>5

after 5 and 10 years respectively. Our results have been obtained assuming a binary period P>5 ![]() 103 (

103 (![]() AU).

Moreover, we derived that we can expect to discover stellar companions

of transiting planets host stars up to a maximum separations

AU).

Moreover, we derived that we can expect to discover stellar companions

of transiting planets host stars up to a maximum separations

![]() AU after 10 years since the discovery of a planet (

AU after 10 years since the discovery of a planet (![]() AU after 5 years).

AU after 5 years).

A final comment is necessary to mention that TTVs may have several different origins among which perturbing effects caused by additional planets or moons, secular precession due to general relativity, stellar proper motion, the Appelgate effect (Agol et al. 2005; Holman & Murray 2005; Veras et al. 2010; Miralda-Escudé 2002; Nesvorný 2009; Heyl & Gladman 2007; Ford & Holman 2007; Simon 2007; Kipping 2009a,b; Pál & Kocsis 2008; Rafikov 2009; Watson 2010), and binarity of the host is one of them. However, transit timing variations induced by binarity are expected to produce long-term trends, and in particular they should be associated also with radial velocity drifts of the host star. Transit timing searchers should also follow-up spectroscopically their targets, since a transit timing variation associated with a radial velocity variation will be very likely the signature of binarity.

AcknowledgementsThe author is grateful to Dr. Daniel Fabrycky, Dr. Francesco Marzari, and Dr. Silvano Desidera for interesting comments and discussions about planets in binary stellar systems, and to the anonymous referee for his/her useful comments and suggestions.

References

- Adams, E. R., López-Morales, M., Elliot, J. L., et al. 2010, ApJ, 714, 13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Agol, E., Steffen, J., Sari, R., & Clarkson, W. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 567 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Artymowicz, P., & Lubow, S. H. 1994, ApJ, 421, 651 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boss, A. P. 1997, Science, 276, 1836 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. M. 2003, ApJ, 593, 125 [Google Scholar]

- Bonavita, M., & Desidera, S. 2007, A&A, 468, 721 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin, G., Lagrange, A.-M., Udry, S., et al. 2006, A&A, 456, 1165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Caton, D. B., Davis, S. A., & Kluttz, K. A. 2000, in BAAS, 32, 1416 [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A. C. M., Udry, S., Mayor, M., et al. 2008, A&A, 479, 271 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Daemgen, S., Hormuth, F., Brandner, W., et al. 2009, A&A, 498, 567 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, H. J., Doyle, L. R., Kozhevnikov, V. P., et al. 1998, A&A, 338, 479 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

-

Deeg, H. J., Oca

a, B., Kozhevnikov, V. P., et al. 2008, A&A, 480, 563

[NASA ADS]

[CrossRef]

[EDP Sciences]

[Google Scholar]

a, B., Kozhevnikov, V. P., et al. 2008, A&A, 480, 563

[NASA ADS]

[CrossRef]

[EDP Sciences]

[Google Scholar]

- Desidera, S., & Barbieri, M. 2007, A&A, 462, 345 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L. R., & Deeg, H.-J. 2004, in Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars, ed. R. Norris, & F. Stootman, IAU Symp., 213, 80 [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L. R., Deeg, H. J., Kozhevnikov, V. P., et al. 2000, ApJ, 535, 338 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Duchêne, G. 2010, ApJ, 709, 114 [Google Scholar]

- Duquennoy, A., & Mayor, M. 1991, A&A, 248, 485 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger, A., & Udry, S. 2007 [arXiv:0705.3173] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger, A., Udry, S., Chauvin, G., et al. 2007, A&A, 474, 273 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger, A., Udry, S., Chauvin, G., et al. 2008, ASPC, 398, 179 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Els, S. G., Sterzik, M. F., Marchis, F., et al. 2001, A&A, 370, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D. A., & Valenti, J. 2005, ApJ, 622, 1102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E. B., & Holman, M. J. 2007, ApJ, 664, 51 [Google Scholar]

- Hatzes, P. A., Cochran, W. D., Endl, M., et al. 2003, ApJ, 599, 1383 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heyl, J. S., & Gladman, B. J. 2007, MNRAS, 377, 1511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Holman, M. J., & Murray, N. W. 2005, Science, 307, 1288 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, J. B. 1959, AJ, 64, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kopal, Z. 1959, Close Binary Systems, The international astrophysics series [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, D. M. 2009a, MNRAS, 392, 181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, D. M. 2009b, MNRAS, 396, 1797 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. W., Kim, S.-L., Kim, C.-H., et al. 2009, AJ, 137, 3181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L., & Jayawardhana, R. 2002, ApJ, 566, 1132 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, D. B. 1924, ApJ, 60, 22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marzari, F., Weidenschilling, S. J., Barbieri, M., et al. 2005, ApJ, 618, 502 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marzari, F., Thébault, P., & Scholl, H. 2009, A&A, 507, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Maxted, P. F. L., Anderson, D. R., Gillon, M., et al. 2010, AJ, accepted[arXiv:1004.1514] [Google Scholar]

- Miralda-Escudé, J. 2002, ApJ, 564, 1019 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

-

Mugrauer, M., Seifahrt, A., & Neuh

user, R. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 1328

[NASA ADS]

[CrossRef]

[Google Scholar]

user, R. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 1328

[NASA ADS]

[CrossRef]

[Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A. F. 2000, ApJ, 537, 65 [Google Scholar]

- Nesvorný, D. 2009, ApJ, 701, 1116 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ofir, A. 2008, MNRAS, 387, 1597 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pál, A., & Kocsis, B. 2008, MNRAS, 389, 191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patience, J., White, R. J., Ghez, A. M., et al. 2002, ApJ, 581, 654 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pfahl, E., & Muterspaugh, M. 2006, ApJ, 652, 1694 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J. B., Hubickyj, O., Bodenheimer, P., et al. 1996, Icarus, 124, 62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Queloz, D., Mayor, M., Weber, L., et al. 2000, A&A, 354, 99 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Queloz, D., Anderson, D., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2010, A&A, 517, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rabus, M., Deeg, H. J., Alonso, R., et al. 2009, A&A, 508, 1011 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rafikov, R. R. 2009, ApJ, 700, 965 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, R. A. 1924, ApJ, 60, 15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N. C., Mayor, M., Naef, D., et al. 2002, A&A, 392, 215 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schnupp, C., Bergfors, C., Brandner, W., et al. 2010, A&A, 516, A21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, A., Szatmáry, K., & Szabó, Gy. M. 2007, A&A, 470, 727 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, C. A., & Marsh, T. R. 2010, MNRAS, 405, 2037 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Triaud, A. H. M. J., Collier Cameron, A., Queloz, D., et al. 2010, A&A, in press [Google Scholar]

- Veras, D., Ford, E. B., & Payne, M. J. 2010, ApJ, submitted [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Mattew, J. H., Joshua, A. C., et al. 2009, AJ, 137, 3826 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., Howard, A. W., et al. 2010, ApJ, 718, 575 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... neglected

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- In particular secular perturbations, see e.g. Kopal (1959) for a discussion of perturbing effects of a third body on a close eclipsing binary.

- ... planet

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- We are assuming that the barycentric radial velocity of the binary stellar system is

.

.

All Tables

Table 1:

Expected frequency (

![]() )

of binary stellar systems detectable by means of transit timing variations in function of the timescale (

)

of binary stellar systems detectable by means of transit timing variations in function of the timescale (![]() )

since the discovery of the planet, and of different assumptions on the inclination of the binary stellar systems.

)

since the discovery of the planet, and of different assumptions on the inclination of the binary stellar systems.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\hspace*{-3mm}\includegraphics[width=7.9cm,clip]{14486fg1a.eps}\vspace*{3mm}

\includegraphics[width=7.6cm,clip]{14486fg1b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 1:

Upper figure, upper panel: the black solid curve represents the

difference between the observed transit ephemerides of the planet once

including the light time effect and the ephemerides obtained once

considering the intrinsic period of the planet

(Eq. (4), see text). The dotted line represents the

accumulation over time of the difference between the observed period of

the planet and its intrinsic period if the planet period is measured at

the epoch t0 coincident with the origin of the x-axis, and it is then assumed constant. Upper figure, lower panel: the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{14486fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14486-10/Timg65.png)

|

Figure 2:

Distributions of the detection probabilities (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.