| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A77 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters, and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014353 | |

| Published online | 15 September 2010 | |

Insights on the Milky Way bulge formation

from the correlations

between kinematics and metallicity![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

C. Babusiaux1 - A. Gómez1 - V. Hill2 - F. Royer1 - M. Zoccali3 - F. Arenou1 - R. Fux4 - A. Lecureur1 - M. Schultheis5 - B. Barbuy6 - D. Minniti3,8 - S. Ortolani7

1 - GEPI, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, 5

Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France

2 - Laboratoire CASSIOPEE, University of Nice Sophia Antipolis, CNRS,

Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France

3 - P. Universidad Católica de Chile, Departamento de Astronomía y

Astrofísica, Casilla 306, Santiago 22, Chile

4 - Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Ch des Maillettes,

1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

5 - Observatoire de Besançon, CNRS UMR6091, BP 1615, 25010 Besançon,

France

6 - Universidade de São Paulo, IAG, Rua do Matão 1226, São Paulo

05508-900, Brazil

7 - Universita di Padova,Vicolo dell'Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova,

Italy

8 - Vatican Observatory, V00120 Vatican City State, Italy

Received 4 March 2010 / Accepted 12 May 2010

Abstract

Context. Two main scenarios for the formation of the

Galactic bulge are invoked, the first one through gravitational

collapse or hierarchical merging of subclumps, the second through

secular evolution of the Galactic disc.

Aims. We aim to constrain the formation of the

Galactic bulge through studies of the correlation between kinematics

and metallicities in Baade's Window (

![]() ,

,

![]() )

and two other fields along the bulge minor axis (

)

and two other fields along the bulge minor axis (

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() ).

).

Methods. We combine the radial velocity and the

[Fe/H] measurements obtained with FLAMES/GIRAFFE at the VLT with a

spectral resolution of R=20 000, plus for

the Baade's Window field the OGLE-II proper motions, and compare these

with published N-body simulations of the Galactic

bulge.

Results. We confirm the presence of two distinct

populations in Baade's Window found in Hill et al. (2010,

A&A, submitted): the metal-rich population presents bar-like

kinematics while the metal-poor population shows kinematics

corresponding to an old spheroid or a thick disc. In this context the

metallicity gradient along the bulge minor axis observed by Zoccali

et al. (2008, A&A, 486, 177), visible also in the

kinematics, can be related to a varying mix of these two populations as

one moves away from the Galactic plane, alleviating the apparent

contradiction between the kinematic evidence of a bar and the existence

of a metallicity gradient.

Conclusions. We show evidence that the two main

scenarios for the bulge formation co-exist within the Milky Way bulge.

Key words: Galaxy: bulge - Galaxy: formation - Galaxy: abundances - Galaxy: kinematics and dynamics

1 Introduction

Although the Milky Way bulge is our closest opportunity to study in detail such a complex chemo-dynamical system, its formation and evolution is still poorly understood. Indeed the high extinction, the crowding, and the superposition of multiple structures along the line of sight make studies of the inner Galactic regions challenging. Two main scenarios have been invoked for bulge formation. The first is gravitational collapse (Eggen et al. 1962) or hierarchical merging of subclumps (Aguerri et al. 2001; Noguchi 1999). There the bulge formed before the disc and the star-formation time-scale was very short. The resulting stars are old (>10 Gyr) and have enhancements ofChemo-dynamical modelling of disc galaxy formation in a Cold

Dark Matter (CDM) universe stresses that both types of bulges can

coexist in the same galaxy. In the Samland

& Gerhard (2003) simulation the bulge contains two

stellar populations, an old population formed during the collapse phase

and a younger bar population, differing in the [![]() /Fe] ratio. Nakasato & Nomoto (2003)

suggest that the Galactic bulge may consist of two chemically different

components: one rapidly formed through subgalactic clump merger in the

proto-Galaxy, and the other one formed later in the inner region of the

disc. The [Fe/H] abundance of the merger component tends to be smaller

than that of the second component. Recently Rahimi

et al. (2010) simulated bulges formed through

multiple mergers and analysed the chemical and dynamical properties of

accreted stars with respect to locally formed stars: accreted stars

tend to form in early epochs and have lower [Fe/H] and higher [Mg/Fe]

ratios, as expected.

/Fe] ratio. Nakasato & Nomoto (2003)

suggest that the Galactic bulge may consist of two chemically different

components: one rapidly formed through subgalactic clump merger in the

proto-Galaxy, and the other one formed later in the inner region of the

disc. The [Fe/H] abundance of the merger component tends to be smaller

than that of the second component. Recently Rahimi

et al. (2010) simulated bulges formed through

multiple mergers and analysed the chemical and dynamical properties of

accreted stars with respect to locally formed stars: accreted stars

tend to form in early epochs and have lower [Fe/H] and higher [Mg/Fe]

ratios, as expected.

Exploring correlations of abundances and kinematics in Baade's Window, Soto et al. (2007) suggest a transition in the kinematics of the bulge, from an isotropic oblate spheroid to a bar, at [Fe/H] = -0.5 dex. Their study was based on 315 K and M giants with proper motions of Spaenhauer et al. (1992), radial velocities of Sadler et al. (1996) and low-resolution abundances of Terndrup et al. (1995) re-calibrated with the iron abundances scale of Fulbright et al. (2006). Similar conclusions were obtained earlier by Zhao et al. (1994) using a sample of 62 K giants who pointed out the triaxiality of the bulge from kinematics in Baade's Window and that the metal-poor and metal-rich populations were not drawn from the same distribution.

We here analyse the correlations between kinematics and

metallicity along three different minor-axis fields: Baade's Window (

![]() ),

),

![]() and

and ![]() ,

for which [Fe/H] abundances (Zoccali

et al. 2008, hereafter Paper I; and Hill et al. 2010,

hereafter Paper III) and radial velocities data for about

700 stars have been determined. Paper II obtained

[Fe/H] and [Mg/H] metallicity distributions for red clump stars in

Baade's Window and showed that the sample seems to be separated into

two different populations in the metallicity distributions. We here use

the kinematic properties of the samples to confirm and constrain the

nature of these two populations in Baade's Window and study their

relative proportion change along the bulge minor axis fields of

Paper I. The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2

summarizes the data used in this study. In Sect. 3 we analyse

Baade's Window by combining our spectroscopic data with OGLE proper

motion data. In Sect. 4 we analyse the radial velocity versus

metallicity trend along the bulge minor axis. In Sect. 5 we

compare our data with some published N-body models.

Section 6 discusses our results.

,

for which [Fe/H] abundances (Zoccali

et al. 2008, hereafter Paper I; and Hill et al. 2010,

hereafter Paper III) and radial velocities data for about

700 stars have been determined. Paper II obtained

[Fe/H] and [Mg/H] metallicity distributions for red clump stars in

Baade's Window and showed that the sample seems to be separated into

two different populations in the metallicity distributions. We here use

the kinematic properties of the samples to confirm and constrain the

nature of these two populations in Baade's Window and study their

relative proportion change along the bulge minor axis fields of

Paper I. The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2

summarizes the data used in this study. In Sect. 3 we analyse

Baade's Window by combining our spectroscopic data with OGLE proper

motion data. In Sect. 4 we analyse the radial velocity versus

metallicity trend along the bulge minor axis. In Sect. 5 we

compare our data with some published N-body models.

Section 6 discusses our results.

2 Data

The different samples are described in detail in Papers I

and II. Only a brief summary is given here. Paper I

samples consist of K giants (called RGB samples

below) observed in the following fields: Baade's Window (

![]() ,

,

![]() :

194 stars);

:

194 stars); ![]() (

(

![]() ,

,

![]() :

201 stars) and

:

201 stars) and

![]() (

(

![]() ,

,

![]() :

99 stars). All stars have photometric V,

I data coming from different sources (for details

see Paper I and Paper II) and 2MASS J,

H, K data. The spectra

have been obtained with VLT/FLAMES-GIRAFFE spectrograph in Medusa mode

at a resolution of about 20 000. The sample of

Paper II, observed in the same conditions, contains 219 red

clump stars (called RC data in what follows) in Baade's Window

(

:

99 stars). All stars have photometric V,

I data coming from different sources (for details

see Paper I and Paper II) and 2MASS J,

H, K data. The spectra

have been obtained with VLT/FLAMES-GIRAFFE spectrograph in Medusa mode

at a resolution of about 20 000. The sample of

Paper II, observed in the same conditions, contains 219 red

clump stars (called RC data in what follows) in Baade's Window

(

![]() ,

,

![]() ).

Iron abundances have been obtained with a mean accuracy of about

0.2 dex, depending on the value of [Fe/H], more metal-rich

stars have the largest errors. In order to increase the statistics, we

combined the two samples of Baade's Window (RC sample of

Paper II and RGB sample of Paper I). Due to a

difference in the reduction process, the two original MDs were not

totally compatible. We therefore used in this combination the new

reduction of the RGB sample made with the Paper II automatic

reduction process (see Sect. 5.1.4 of Paper II),

which lead to two compatible MDs, which we can therefore combine in

Sect. 3

of this study. However, we note that according to the Besançon model (Robin et al. (2003), see

Fig. 9 of Paper II and Fig. 10 of

Paper I), the two selections have slightly different mean

distance and contamination. In Sect. 4 the other

minor axis fields at

).

Iron abundances have been obtained with a mean accuracy of about

0.2 dex, depending on the value of [Fe/H], more metal-rich

stars have the largest errors. In order to increase the statistics, we

combined the two samples of Baade's Window (RC sample of

Paper II and RGB sample of Paper I). Due to a

difference in the reduction process, the two original MDs were not

totally compatible. We therefore used in this combination the new

reduction of the RGB sample made with the Paper II automatic

reduction process (see Sect. 5.1.4 of Paper II),

which lead to two compatible MDs, which we can therefore combine in

Sect. 3

of this study. However, we note that according to the Besançon model (Robin et al. (2003), see

Fig. 9 of Paper II and Fig. 10 of

Paper I), the two selections have slightly different mean

distance and contamination. In Sect. 4 the other

minor axis fields at ![]() and

and ![]() are compared with the Baade's Window data and, to be consistent, we

will use only the original RGB data of Baade's Window computed in

Paper I in this comparison.

are compared with the Baade's Window data and, to be consistent, we

will use only the original RGB data of Baade's Window computed in

Paper I in this comparison.

Radial velocities were obtained with the cross-correlation

tool available in the GIRAFFE reduction pipeline (Royer

et al. 2002). The individual spectra were

cross-correlated with a box-shaped template corresponding to a K0 giant

star. For each target, the barycentric radial velocities derived for

each exposure were combined into an average velocity, and the standard

deviation was used as an error estimate. The median error of the

combined velocities range from 0.26 to 0.43 km s-1

for the different fields. Throughout this paper, ![]() stands for the heliocentric radial velocity.

stands for the heliocentric radial velocity.

OGLE-II proper motions (Sumi et al. 2004) are only available for the Baade's Window field. We removed stars with less than 100 data points used in the proper motion computation. Those removed stars are either near the edge of the CCD image or CCD defects or affected by blending. In the present paper the mas/yr has been converted in km s-1 assuming a distance to the Galactic Centre of 8 kpc (1 mas/yr = 37.9 km s-1). The mean error on the proper motions of our sample is 1.24 mas/yr, i.e. 47 km s-1. We worked on the relative values of the proper motions as provided in the catalogue. Section 6 of Sumi et al. (2004) details how one can transform the catalogue into an inertial frame based on the measured proper motions for the Galactic Centre (GC). Our data cover fields BUL_SC45 and BUL_SC46, which do not show any difference in the proper motions of the GC (Table 3 of Sumi et al. 2004) so that the relative zero-points from these two fields do not need to be taken into account.

Throughout this paper errors will be computed from a bootstrap analysis using 1000 samplings of the datasets.

3 Analysis of Baade's Window

Our sample of 340 stars in Baade's Window is at present the largest one

that has proper motions, radial velocities and homogeneous iron

abundances determinations. This sample combines both the Baade's Window

dataset of Paper I (RGB sample) and the dataset of

Paper II (RC sample) with metallicities derived in an

homogeneous way by Paper II.

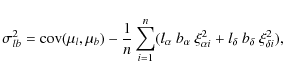

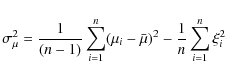

We computed the proper motion dispersions following the equations in Spaenhauer et al. (1992):

|

(1) |

with

The covariance ![]() ,

used in the computation of correlations between the different velocity

components and in the velocity ellipsoid angles, also needs to be

corrected from measurement errors due to the transformation from image

coordinates to galactic proper motions. Indeed we have

,

used in the computation of correlations between the different velocity

components and in the velocity ellipsoid angles, also needs to be

corrected from measurement errors due to the transformation from image

coordinates to galactic proper motions. Indeed we have

with the errors in the equatorial proper motions un-correlated (Sumi 2010, private communication), which implies

with

Our Baade's Window radial velocity measurements

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1

excellently agree with previous studies: Howard

et al. (2008):

km s-1

excellently agree with previous studies: Howard

et al. (2008):

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1,

Rangwala et al. (2009):

km s-1,

Rangwala et al. (2009):

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1,

and other measurements listed in Rangwala

et al. (2009).

The proper motion dispersions

km s-1,

and other measurements listed in Rangwala

et al. (2009).

The proper motion dispersions

![]() mas/yr

and

mas/yr

and ![]() mas/yr

also excellently agree with the high-accuracy HST

measurements of Kozowski

et al. (2006):

mas/yr

also excellently agree with the high-accuracy HST

measurements of Kozowski

et al. (2006):

![]() ,

,

![]() mas/yr.

mas/yr.

3.1 Kinematics versus metallicity

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14353Fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 1:

Dispersion of the radial (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 1

plots the dispersion of velocity components along the line-of-sight (

![]() ), the galactic longitude (

), the galactic longitude (

![]() )

and the galactic latitude (

)

and the galactic latitude (

![]() )

as a function of [Fe/H]. The figure shows that

)

as a function of [Fe/H]. The figure shows that

![]() increases with metallicity, while

increases with metallicity, while

![]() decreases. No significant variation of

decreases. No significant variation of

![]() is seen. To quantify if these variations are indeed significant, we

used the F-test to compare the variances of the velocity distributions

for the first and last 33% quantiles ([Fe/H]<-0.14 and

[Fe/H]>0.30):

is seen. To quantify if these variations are indeed significant, we

used the F-test to compare the variances of the velocity distributions

for the first and last 33% quantiles ([Fe/H]<-0.14 and

[Fe/H]>0.30): ![]() and

and ![]() are indeed significantly different (p-value = 0.04

and 0.01 respectively), while the variation in

are indeed significantly different (p-value = 0.04

and 0.01 respectively), while the variation in

![]() is not significant (p-value = 0.2). These results do

not confirm those of Soto

et al. (2007). Their study, based on a compiled

sample of proper motions, radial velocities and low-resolution

abundances, showed only a rather shallow variation in

is not significant (p-value = 0.2). These results do

not confirm those of Soto

et al. (2007). Their study, based on a compiled

sample of proper motions, radial velocities and low-resolution

abundances, showed only a rather shallow variation in

![]() ,

in the sense that the more metal-poor stars have a higher

,

in the sense that the more metal-poor stars have a higher

![]() value. The discrepancies with the study of Soto

et al. (2007) may partly come from the sample

itself. Our results are based on more accurate and homogeneous

spectroscopic data. The different contamination of the sample by

foreground objects may also be another source of discrepancy. Recently,

Clarkson et al. (2008)

constructed the {l,b} velocity

ellipse as a function of line-of-sight distance from HST

proper motions and estimated photometric parallaxes in the Sagittarius

Window and demonstrated that its properties are sensitive to the

distance to the considered objects. They concluded that the

depth-integrated velocity ellipsoid of a small population of objects

should be treated with caution. Half of our sample are red clump stars,

while Soto et al. (2007)

studied M giants, so we expect our sample to be less biased towards

closer stars.

value. The discrepancies with the study of Soto

et al. (2007) may partly come from the sample

itself. Our results are based on more accurate and homogeneous

spectroscopic data. The different contamination of the sample by

foreground objects may also be another source of discrepancy. Recently,

Clarkson et al. (2008)

constructed the {l,b} velocity

ellipse as a function of line-of-sight distance from HST

proper motions and estimated photometric parallaxes in the Sagittarius

Window and demonstrated that its properties are sensitive to the

distance to the considered objects. They concluded that the

depth-integrated velocity ellipsoid of a small population of objects

should be treated with caution. Half of our sample are red clump stars,

while Soto et al. (2007)

studied M giants, so we expect our sample to be less biased towards

closer stars.

Table 1: Baade's Window velocity ellipsoid parameters.

Below we analyse the shape and the orientation of the velocity

ellipsoid for the data sets quoted in Table 1. From the whole

sample, the observed anisotropy in

![]() agrees well with the results of Spaenhauer

et al. (1992), Feltzing

& Johnson (2002), Kuijken

& Rich (2002) and Kozowski

et al. (2006). We also detected an anisotropy in

agrees well with the results of Spaenhauer

et al. (1992), Feltzing

& Johnson (2002), Kuijken

& Rich (2002) and Kozowski

et al. (2006). We also detected an anisotropy in

![]() and not a significant one in

and not a significant one in

![]() .

Because the kinematic properties of the whole sample is an average of

the properties of distinct populations, we analyse the shape of the

velocity ellipsoid of the two metallicity samples.

.

Because the kinematic properties of the whole sample is an average of

the properties of distinct populations, we analyse the shape of the

velocity ellipsoid of the two metallicity samples.

The metal-poor sample ([Fe/H]<-0.14) shows a

![]() higher than the other components,

higher than the other components,

![]() ,

and an anisotropy in

,

and an anisotropy in

![]() (confirmed by an F-test with a 98% confidence) and in

(confirmed by an F-test with a 98% confidence) and in

![]() (an F-test cannot be performed here due to the large difference in the

errors in the proper motion and radial velocity measurements).

Following Zhao et al.

(1996), the observed anisotropies for the metal-poor sample (

(an F-test cannot be performed here due to the large difference in the

errors in the proper motion and radial velocity measurements).

Following Zhao et al.

(1996), the observed anisotropies for the metal-poor sample (

![]() )

may be interpreted in terms of rotation broadening: as Baade's Window

passes close to the minor axis of the bulge, only

)

may be interpreted in terms of rotation broadening: as Baade's Window

passes close to the minor axis of the bulge, only

![]() should be broadened by the rotation, which is indeed what is observed.

However, a possible contamination with foreground thick disc stars

higher than expected would also contribute to an increase in

should be broadened by the rotation, which is indeed what is observed.

However, a possible contamination with foreground thick disc stars

higher than expected would also contribute to an increase in ![]() .

.

For the metal-rich sample ([Fe/H]>0.30) the shape of

the velocity ellipsoid is significantly different from the metal-poor

sample. We observe for the metal-rich population

![]() ,

and that

,

and that ![]() is higher (with 96% confidence) and

is higher (with 96% confidence) and ![]() is lower (with 99% confidence) than the observed values for the

metal-poor sample. In the case of a bar, the velocity dispersion along

the bar major axis is expected to be much larger than its azimuthal

dispersion, which is itself smaller than its vertical dispersion. If

the bar was pointing nearly end-on, that would mean

is lower (with 99% confidence) than the observed values for the

metal-poor sample. In the case of a bar, the velocity dispersion along

the bar major axis is expected to be much larger than its azimuthal

dispersion, which is itself smaller than its vertical dispersion. If

the bar was pointing nearly end-on, that would mean

![]() ,

which is what we observe. The anisotropy in

,

which is what we observe. The anisotropy in

![]() observed for the metal-rich sample may be explained by the flattening

of the bar-driven population.

observed for the metal-rich sample may be explained by the flattening

of the bar-driven population.

The Baade's Window velocity ellipsoid shows the

characteristics of a non-axisymmetric system. We now analyse the

orientation of the velocity ellipsoid. We first examine the

correlations between the different velocity components. The obtained

cross-correlation terms (

![]() ,

,

![]() being

the covariance) are given in Table 1.

being

the covariance) are given in Table 1.

Clb

is higher than the results of Kozowski

et al. (2006) (

![]() )

and Rattenbury et al.

(2007) (

)

and Rattenbury et al.

(2007) (

![]() ).

We note that Rattenbury

et al. (2007) used the same OGLE-II data but

selected only stars with errors in the proper motion smaller than

1 mas/yr, introducing a bias towards closer stars, but

reducing the impact of the correction described in Eq. (2).

).

We note that Rattenbury

et al. (2007) used the same OGLE-II data but

selected only stars with errors in the proper motion smaller than

1 mas/yr, introducing a bias towards closer stars, but

reducing the impact of the correction described in Eq. (2).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14353Fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg72.png)

|

Figure 2:

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

A decrease with metallicity of the correlations between the velocity

components seems to be present in our sample. We now quantify the

observed correlations in terms of velocity ellipsoid angles in

Table 1

with

|

(3) |

Below we will call the vertex deviation

Our derived value of

![]() is consistent with the results of Clarkson

et al. (2008) (

is consistent with the results of Clarkson

et al. (2008) (

![]() )

and Kozowski et al. (2006)

(

)

and Kozowski et al. (2006)

(

![]() ).

It shows a significant variation with metallicity. The Pearson's

correlation test indicates a correlation with 99% confidence for the

metal-rich sample, while the metal-poor sample correlation is not

significant (p-value = 0.1).

).

It shows a significant variation with metallicity. The Pearson's

correlation test indicates a correlation with 99% confidence for the

metal-rich sample, while the metal-poor sample correlation is not

significant (p-value = 0.1).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14353Fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg80.png)

|

Figure 3: Vertex deviation lv in Baade's Window as a function of metallicity by bins of 0.4 dex. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We measured ![]() for the first time. The Pearson's correlation test does not show a

significant correlation between

for the first time. The Pearson's correlation test does not show a

significant correlation between ![]() and

and ![]() for the metal-poor sample (p-value = 0.3), while it

finds the correlation to be significant for the metal-rich sample with

99.9% confidence.

for the metal-poor sample (p-value = 0.3), while it

finds the correlation to be significant for the metal-rich sample with

99.9% confidence.

Following Paper II, we applied the SEMMUL Gaussian

components decomposition algorithm (Celeux

& Diebolt 1986) to the [Fe/H] distribution of the

full Baade's Window sample and find a decomposition fully compatible

with the Paper II results (which were based on the red clump

sample only): the decomposition clearly identifies two populations, in

roughly equal proportions, a metal-poor component (46 ![]() 3%

of the sample,

3%

of the sample, ![]() Fe/H

Fe/H

![]() )

with a large dispersion (0.23

)

with a large dispersion (0.23 ![]() 0.01 dex) and a metal-rich

component (54

0.01 dex) and a metal-rich

component (54 ![]() 3%

of the sample,

3%

of the sample, ![]() Fe/H

Fe/H

![]() )

with a small dispersion (0.11

)

with a small dispersion (0.11 ![]() 0.01 dex). The variation of

the kinematic properties between the metal-rich and the metal-poor

parts of the sample studied here suggests different formation scenarii

for those populations. The metal-poor component of our sample shows

0.01 dex). The variation of

the kinematic properties between the metal-rich and the metal-poor

parts of the sample studied here suggests different formation scenarii

for those populations. The metal-poor component of our sample shows

![]() higher than

higher than ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

a strong anisotropy in

,

a strong anisotropy in ![]() and

and ![]() and no correlations between the velocity components. This population

can be interpreted as a spheroidal population with the velocity

anisotropy due mostly to rotation that broadens the observed

and no correlations between the velocity components. This population

can be interpreted as a spheroidal population with the velocity

anisotropy due mostly to rotation that broadens the observed

![]() component. The metal-rich population shows significant anisotropy and

correlation between all the velocity components. In particular the

strong vertex deviation indicates that it can be interpreted as a

bar-driven population.

component. The metal-rich population shows significant anisotropy and

correlation between all the velocity components. In particular the

strong vertex deviation indicates that it can be interpreted as a

bar-driven population.

3.2 Kinematics versus distance

We used our red clump stars sample to probe the kinematics against distance. Red clump stars should indeed allow to measure the velocity shift between the two bar streams (Mao & Paczynski 2002; Rangwala et al. 2009). As the stars form, the bar streams in the same sense as the Galactic rotation, and because the bar is in the first quadrant, the stars on the near side of the bar are expected to go towards us, while stars on the far side should move away from us. The actual velocity shifts between these two streams constrains the bar orientation angle.

The Besançon model confirms that our red clump sample should

be nicely centred around the Galactic Centre (see Fig. 9 of

Paper II). The magnitude I is less

sensitive than magnitude K to both the metallicity

and the age for ages older than ![]() 4 Gyr (Salaris

& Girardi 2002). Moreover the I magnitude

is more sensitive to the extinction, which itself increases with

distance, leading the I magnitude to be

much more sensitive to distance than K. No

differential extinction pattern is seen in the region of our sample (Sumi 2004).

4 Gyr (Salaris

& Girardi 2002). Moreover the I magnitude

is more sensitive to the extinction, which itself increases with

distance, leading the I magnitude to be

much more sensitive to distance than K. No

differential extinction pattern is seen in the region of our sample (Sumi 2004).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14353Fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg88.png)

|

Figure 4:

Distribution of the I magnitude and |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 2: Baade's Window red clump mean velocities for the faint and bright stars in magnitude I (first and the last 25% quantiles) for stars with [Fe/H] >-0.09 (33% quantile of the [Fe/H] distribution).

Table 3:

Summary of the bulge minor axis fields (Paper I)

characteristics. ![]() is the height of the field along the bulge minor axis, assuming a

distance Sun - Galactic Centre of 8 kpc.

is the height of the field along the bulge minor axis, assuming a

distance Sun - Galactic Centre of 8 kpc.

We cut our sample into bright and faint stars on the first and

last 25% quantile of our I magnitude distribution

(Fig. 4)

and computed the mean velocities. Without selection in metallicity, the

Welch Two Sample t-test does not indicate that the mean values between

the bright and the faint samples are significant (p-value

= 0.1 for ![]() ,

0.1 for

,

0.1 for ![]() and 0.8 for

and 0.8 for ![]() ).

By removing the metal-poor stars (selecting [Fe/H]>-0.09, which

corresponds to the 66% quantile of the [Fe/H] distribution), the Welch

Two Sample t-test becomes significant on the radial velocities (p-value

= 0.02 for

).

By removing the metal-poor stars (selecting [Fe/H]>-0.09, which

corresponds to the 66% quantile of the [Fe/H] distribution), the Welch

Two Sample t-test becomes significant on the radial velocities (p-value

= 0.02 for ![]() ,

0.2 for

,

0.2 for ![]() and 0.4 for

and 0.4 for ![]() ).

The resulting values are presented in Table 2. The numbers

go in the expected direction, which is a negative

).

The resulting values are presented in Table 2. The numbers

go in the expected direction, which is a negative ![]() and a positive

and a positive ![]() for the near stream and a positive

for the near stream and a positive ![]() with a negative

with a negative ![]() for the far stream. Note that the mean proper motions quoted in

Table 2

are relative. By removing the metal-rich stars from the sample

(selecting [Fe/H]<0.33, which corresponds to the 66% quantile of

the [Fe/H] distribution), the Welch Two Sample t-test does not

distinguish differences between the faint and the bright sample (p-value

= 0.5 for

for the far stream. Note that the mean proper motions quoted in

Table 2

are relative. By removing the metal-rich stars from the sample

(selecting [Fe/H]<0.33, which corresponds to the 66% quantile of

the [Fe/H] distribution), the Welch Two Sample t-test does not

distinguish differences between the faint and the bright sample (p-value

= 0.5 for ![]() ,

0.2 for

,

0.2 for ![]() and 0.9 for

and 0.9 for ![]() ).

This again confirms our interpretation of the metal-rich population of

Baade's Window being associated to the bar and the metal-poor

population to a spheroidal population.

).

This again confirms our interpretation of the metal-rich population of

Baade's Window being associated to the bar and the metal-poor

population to a spheroidal population.

This shift was not seen in the radial velocities of Rangwala et al. (2009). They argue that this may be because Baade's Window population is the superposition of an old spheroidal population and a bar population, which we here confirm.

No correlation of the kinematics with the magnitude I

can be seen for the RGB sample. We note that the RGB sample is biased

towards closest stars. According to the Besançon model, the median

distance difference between the RC and the RGB sample is

expected to be 1 kpc (see Fig. 9 of Paper II

for the RC and Fig. 10 of Paper I for the

RGB sample). This bias in distance is not significant in the mean

kinematics of the RGB sample (

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() mas/yr,

mas/yr,

![]() mas/yr).

mas/yr).

4 Radial velocity versus metallicity along the bulge minor axis

We now wonder whether the two distinct stellar populations found in the

previous section are present all along the

bulge minor axes. We analyse the radial velocity distribution behaviour

of the fields of Paper I, presented in Table 3. To be

consistent with the ![]() and

and ![]() metallicity distribution, we will use only the RGB sample of Baade's

Window with the original metallicity distribution function of

Paper I. Paper I showed a variation of the

metallicity distribution with height z above the

Galactic mid-plane (Fig. 5). In this

section we combine the metallicity data with radial velocity data.

Figure 6

shows the radial velocity dispersion as a function of metallicity.

metallicity distribution, we will use only the RGB sample of Baade's

Window with the original metallicity distribution function of

Paper I. Paper I showed a variation of the

metallicity distribution with height z above the

Galactic mid-plane (Fig. 5). In this

section we combine the metallicity data with radial velocity data.

Figure 6

shows the radial velocity dispersion as a function of metallicity.

We first compare the kinematic behaviour along the bulge minor

axis (Table 3)

with previous results from the literature. We saw in Sect. 3

that our Baade's Window radial velocity dispersion excellently agrees

with previous measurements. At

![]() our radial velocity dispersion is lower than the BRAVA measure (

our radial velocity dispersion is lower than the BRAVA measure (

![]() km s-1,

Howard et al. 2008).

The decrease of the radial velocity dispersion with galactic latitude

we observe is consistent with the SiO maser measurements of Izumiura et al. (1995).

km s-1,

Howard et al. 2008).

The decrease of the radial velocity dispersion with galactic latitude

we observe is consistent with the SiO maser measurements of Izumiura et al. (1995).

All fields show a negligible skew, while the kurtosis is

different. This variation of the kurtosis was not detected in Howard et al. (2008). At

![]() the

distribution is significantly pointy (with 99.3% confidence according

to the Anscombe-Glynn kurtosis test), indicating that the kinematics

are significantly affected by the disc. At

the

distribution is significantly pointy (with 99.3% confidence according

to the Anscombe-Glynn kurtosis test), indicating that the kinematics

are significantly affected by the disc. At

![]() the kurtosis becomes consistent with zero. In Baade's Window the

distribution is significantly flattened (with 93% confidence in the RGB

sample and 99.8% in the red clump sample). Sharples

et al. (1990) and Rangwala

et al. (2009) also measured a skew consistent with

zero and kurtosis significantly negative in Baade's Window, indicating

that the distributions are flat-topped rather than peaked. Rangwala et al. (2009)

concludes that this seems to be consistent with a model of the bar with

stars in elongated orbits forming two streams at different mean radial

velocities, broadening and flattening the total distribution.

the kurtosis becomes consistent with zero. In Baade's Window the

distribution is significantly flattened (with 93% confidence in the RGB

sample and 99.8% in the red clump sample). Sharples

et al. (1990) and Rangwala

et al. (2009) also measured a skew consistent with

zero and kurtosis significantly negative in Baade's Window, indicating

that the distributions are flat-topped rather than peaked. Rangwala et al. (2009)

concludes that this seems to be consistent with a model of the bar with

stars in elongated orbits forming two streams at different mean radial

velocities, broadening and flattening the total distribution.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14353Fig5.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg103.png)

|

Figure 5: Distribution of the metallicity for the different galactic latitudes of Paper I. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14353Fig6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg104.png)

|

Figure 6: Dispersion of the radial velocity for the different galactic latitudes as a function of metallicity by bins of 0.4 dex. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We now analyse kinematic data versus metallicity. The mean radial

velocities do not show significant variation with metallicity in any of

our fields. Figure 6

shows that the velocity dispersion at the rich end decreases

significantly with latitude. However, the velocity dispersion on the

metal-poor end does not vary significantly with latitude. Summing all

stars with [Fe/H] < -0.5 dex in all fields leads to

![]() km s-1.

km s-1.

The field ![]() is close enough to Plaut's Window (

is close enough to Plaut's Window (

![]() ,

,

![]() )

so that we can compare our results to the proper motion study of Vieira et al. (2007).

The Besançon model indicates a mean distance of our selected bulge

stars to be 6.5 kpc, compatible with the Vieira et al. (2007)

selection. Their metallicity distribution is compatible with ours. They

do not find any change in the proper motion dispersion as a function of

metallicity either. They found

)

so that we can compare our results to the proper motion study of Vieira et al. (2007).

The Besançon model indicates a mean distance of our selected bulge

stars to be 6.5 kpc, compatible with the Vieira et al. (2007)

selection. Their metallicity distribution is compatible with ours. They

do not find any change in the proper motion dispersion as a function of

metallicity either. They found

![]() km s-1

and

km s-1

and ![]() km s-1

at

km s-1

at ![]() ,

we obtain

,

we obtain ![]() km s-1

at

km s-1

at ![]() ,

leading to a full picture coherent with the predictions of the model of

Zhao (1996) of

,

leading to a full picture coherent with the predictions of the model of

Zhao (1996) of

![]() and

and ![]() at these latitudes (see the bottom of Fig. 6 of Zhao 1996).

at these latitudes (see the bottom of Fig. 6 of Zhao 1996).

We have seen in the previous section that Baade's Window kinematic behaviour as a function of metallicity can be interpreted as a mix of two populations, a metal-poor component with kinematics that can be associated to an old spheroid population and a metal-rich component with bar-driven kinematics. In this light we can interpret the variation with galactic latitude of both the metallicity distribution function (Fig. 5) and the kinematics as a function of metallicity (Fig. 6) as the bar population disappearing while moving away from the plane. At high latitudes the foreground disc component dominates the metal-rich part of the kinematic behaviour. The metal-poor component associated with the old spheroid stays present along the bulge minor axis.

We obtained an estimation of the variation of the populations

with latitude by using the SEMMUL Gaussian components decomposition in

the metallicity distribution of the Paper I samples.

Table 4

gives the decomposition of the Baade's Window RGB sample. The

proportion of the metal-rich component is higher than in the red clump

sample of Paper II and its spread in metallicity is also

higher, most probably due to a difference in the sample selection,

which is biased towards stars closer to the Sun in the RGB sample.

Although both samples are not exactly on the same scale at the

high-metallicity end (cf. Sect. 5.1.4 of Paper II), the mean

metallicities for the metal-poor population is extremely similar in

both samples (see also the decomposition of the full Baade's Window

sample on the same metallicity scale at the end of Sect. 3.1).

At ![]() the Wilks' test allows us to keep a solution with three components

presented in Table 5

rather than the two components. Population A and population B could

correspond to the population A and B observed in Baade's Window. The

mean metallicities are coherent although their spread is smaller. The

radial velocity dispersions of population A are identical. The radial

velocity dispersion of population B decreases at

the Wilks' test allows us to keep a solution with three components

presented in Table 5

rather than the two components. Population A and population B could

correspond to the population A and B observed in Baade's Window. The

mean metallicities are coherent although their spread is smaller. The

radial velocity dispersions of population A are identical. The radial

velocity dispersion of population B decreases at

![]() as expected for a bar-like kinematic behaviour (see Fig. 8 and

associated text). Population C represents only

as expected for a bar-like kinematic behaviour (see Fig. 8 and

associated text). Population C represents only ![]() % of the sample with a low

mean metallicity of

% of the sample with a low

mean metallicity of ![]() dex and a high-velocity dispersion of

dex and a high-velocity dispersion of ![]() km s-1,

which could therefore be associated to the halo. The Besançon model

prediction of only

km s-1,

which could therefore be associated to the halo. The Besançon model

prediction of only ![]() %

of halo star in the sample could therefore have been underestimated.

This population could also have been hidden in the population A at

%

of halo star in the sample could therefore have been underestimated.

This population could also have been hidden in the population A at

![]() .

Selecting all stars with [Fe/H]<-0.9 in our three fields we

obtain 16 stars with a radial velocity dispersion of

.

Selecting all stars with [Fe/H]<-0.9 in our three fields we

obtain 16 stars with a radial velocity dispersion of

![]() km s-1,

which is coherent with the solar neighbourhood velocity dispersions

measured in this metallicity range (e.g. Chiba

& Beers 2000:

km s-1,

which is coherent with the solar neighbourhood velocity dispersions

measured in this metallicity range (e.g. Chiba

& Beers 2000:

![]() km s-1)

containing both thick disc and halo stars. We are not in a position to

clearly associate this population either to the halo or to a metal-poor

thick disc in our inner galactic samples. SEMMUL did not converge on

the

km s-1)

containing both thick disc and halo stars. We are not in a position to

clearly associate this population either to the halo or to a metal-poor

thick disc in our inner galactic samples. SEMMUL did not converge on

the ![]() field due to the smaller number of stars and the higher contamination

with thin, thick discs and halo stars expected in this field. At

field due to the smaller number of stars and the higher contamination

with thin, thick discs and halo stars expected in this field. At

![]() the metal-rich component present at

the metal-rich component present at

![]() and

and ![]() seems to have fully disappeared. The metal-rich velocity part of the

velocity dispersion corresponds to a disc-like component (see next

section), while the metal-poor part shows a velocity dispersion still

coherent with the metal-poor population of

seems to have fully disappeared. The metal-rich velocity part of the

velocity dispersion corresponds to a disc-like component (see next

section), while the metal-poor part shows a velocity dispersion still

coherent with the metal-poor population of

![]() and

and ![]() ,

although we cannot distinguish a spheroid and a thick disc

contribution.

,

although we cannot distinguish a spheroid and a thick disc

contribution.

Table 4:

SEMMUL Gaussian components decomposition of field

![]() ,

RGB sample only.

,

RGB sample only.

Table 5:

SEMMUL Gaussian components decomposition of field

![]() .

.

5 Comparison with dynamical models

In this section we combine the full Baade's Window sample of

Sect. 3 with the b=-6![]() and b=-12

and b=-12![]() fields of Sect. 4.

fields of Sect. 4.

We first compared our kinematics with the model of Zhao (1996) in Baade's Window (Table 1) and along the minor axis (Fig. 7). The model of Zhao (1996) is a 3D steady-state stellar model using a generalized Schwarzschild technique consisting of orbital building blocks within a bar and a disc potential. We find a very good agreement between our data and this model. Figure 7 also shows the very good agreement of our radial velocity distribution along the minor axis with the BRAVA data (Howard et al. 2009,2008). These comparisons are done on global kinematics, while we have shown here that several populations are present in these data.

The N-body dynamical model of Fux (1999) allows us to compare the

kinematic properties of the particles that were originally in the disc

to those in the old spheroid. This model is a 3D self-consistent,

symmetry-free N-body and smooth particle

hydrodynamics code. It contains 3.8 million particles: a dark

halo, a disc, a spheroid, and a gas component. Following Howard et al. (2009) we

used the model c10t2066 described in Fux

(1999), which assumes a bar angle of 20![]() and a distance to the Sun of 8 kpc. We selected

particles at a distance from the Sun 6<r<10 kpc

in a cone selection of 0.5 degree radius for

and a distance to the Sun of 8 kpc. We selected

particles at a distance from the Sun 6<r<10 kpc

in a cone selection of 0.5 degree radius for

![]() and in a cone selection of 1 degree for

and in a cone selection of 1 degree for

![]() to permit us to work with a sample away from the plane large enough

(this larger cone leads to 209 particles at

to permit us to work with a sample away from the plane large enough

(this larger cone leads to 209 particles at

![]() ).

We computed statistical uncertainties of the model by bootstrap of

2-3 km s-1 in the velocity

dispersions and 5

).

We computed statistical uncertainties of the model by bootstrap of

2-3 km s-1 in the velocity

dispersions and 5

![]() in the velocity ellipsoid

angles for the disc/bar, 20

in the velocity ellipsoid

angles for the disc/bar, 20

![]() for the spheroid.

for the spheroid.

Table 1

shows the predictions of the model of Fux

(1999) in Baade's Window. In this field the model contains

50% of stars from the spheroid and 50% from the disc/bar population,

equivalent to the SEMMUL Gaussian components decomposition we obtained

for the red clump sample in Paper II. The velocity dispersions

of the model are slightly higher than our observed ones and the

velocity component correlations are lower. The velocity

dispersions of the metal-rich population correspond to the disc/bar

particles except for ![]() ,

which is higher in the model. Both metal-rich observations and disc/bar

particles show a correlation of the velocity components, but the

correlations in the observations are higher. The vertex deviation is

however identical in the model and the observations. The metal-poor

component show smaller velocity dispersions in

,

which is higher in the model. Both metal-rich observations and disc/bar

particles show a correlation of the velocity components, but the

correlations in the observations are higher. The vertex deviation is

however identical in the model and the observations. The metal-poor

component show smaller velocity dispersions in

![]() and

and ![]() than the spheroid model particles. As expected the model does not show

any correlations in the velocity components of the spheroid particles,

in line with our metal-poor sample.

than the spheroid model particles. As expected the model does not show

any correlations in the velocity components of the spheroid particles,

in line with our metal-poor sample.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.2cm,clip]{14353Fig7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg132.png)

|

Figure 7: Radial velocity dispersion along the bulge minor axis compared to the BRAVA data (; Howard et al. 2008) and the model of Zhao (1996). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 8

shows the strong decrease in radial velocity dispersion predicted by

the Fux model for the disc/bar population while moving away from the

plane. In the plane the predicted dispersion is larger for the disc/bar

than the spheroid one, due to the influence of the bar driven orbits.

At high latitude the ![]() dispersion is small for the bar/disc component, following a disc-like

behaviour. The spheroid population keeps the same velocity dispersion

along the minor axis. In Fig. 8 we

over-plotted the Fux model radial velocity dispersions with our data

for the full sample, the metal-rich and the metal-poor parts, as

defined by the 33% and 66% quantiles in the [Fe/H] distribution. For

the metal-rich part we observe a strong decrease of the metallicity

dispersion while going away from the plane, which is coherent with the

behaviour of the disc/bar particles of Fux model. For the metal-poor

part we observe a constant velocity dispersion, similar to the spheroid

particles of the Fux model, but with a mean velocity dispersion of

about 20 km s-1 lower than the

model. It is this difference of velocity dispersion for the metal-poor

component which leads to a too high global velocity dispersion of the

Fux model compared to the BRAVA data, which in turn lead Howard et al. (2009) to

an interpretation different from ours: at

dispersion is small for the bar/disc component, following a disc-like

behaviour. The spheroid population keeps the same velocity dispersion

along the minor axis. In Fig. 8 we

over-plotted the Fux model radial velocity dispersions with our data

for the full sample, the metal-rich and the metal-poor parts, as

defined by the 33% and 66% quantiles in the [Fe/H] distribution. For

the metal-rich part we observe a strong decrease of the metallicity

dispersion while going away from the plane, which is coherent with the

behaviour of the disc/bar particles of Fux model. For the metal-poor

part we observe a constant velocity dispersion, similar to the spheroid

particles of the Fux model, but with a mean velocity dispersion of

about 20 km s-1 lower than the

model. It is this difference of velocity dispersion for the metal-poor

component which leads to a too high global velocity dispersion of the

Fux model compared to the BRAVA data, which in turn lead Howard et al. (2009) to

an interpretation different from ours: at

![]() the radial velocity distribution is compatible with the disc/bar

component of the Fux model without the need for an old spheroid

component. However, with a velocity dispersion for the spheroid of

the radial velocity distribution is compatible with the disc/bar

component of the Fux model without the need for an old spheroid

component. However, with a velocity dispersion for the spheroid of ![]() 100 km s-1

instead of

100 km s-1

instead of ![]() 120 km s-1

the global velocity dispersion would be coherent with the full Fux

model (spheroid+disc). The use of the Besançon model adds support to

the interpretation that the decrease in

120 km s-1

the global velocity dispersion would be coherent with the full Fux

model (spheroid+disc). The use of the Besançon model adds support to

the interpretation that the decrease in

![]() with latitude, seen in disc/bar particles of Fux

(1999) and in our metal-rich samples, can be due to the disc

replacing the bar in the sample: according to the Besançon model, the

thin disc contamination of our sample at

with latitude, seen in disc/bar particles of Fux

(1999) and in our metal-rich samples, can be due to the disc

replacing the bar in the sample: according to the Besançon model, the

thin disc contamination of our sample at

![]() was expected to be of 10% with a

was expected to be of 10% with a

![]() km s-1

and 19% at

km s-1

and 19% at ![]() with

with ![]() km s-1.

km s-1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14353Fig8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14353-10/Timg135.png)

|

Figure 8: Radial velocity dispersion along the bulge minor axis compared with the model of Fux (1999). The metal-poor and metal-rich population are defined by the 33% and 66% quantile of the [Fe/H] distribution. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Discussion

Our analysis of the kinematics as a function of metallicity in Baade's Window shows that our sample can be decomposed into two distinct populations, for which we suggest different formation scenarii. The metal-poor component does not show any correlation between its velocity components and is therefore consistent with an isotropic rotating population. Paper II showed that this component is enriched in [Mg/Fe]. We interpret this population as an old spheroid with a rapid time-scale formation. The metal-rich component shows a vertex deviation consistent with that expected from a population with orbits supporting a bar. Paper II showed that this component has a [Mg/Fe] near solar. We interpret this population as a pseudo-bulge formed over a long time-scale through disc secular evolution under the action of a bar. This pseudo-bulge is gradually disappearing when moving away from the Galactic plane.

In this context we can give a new consistent interpretation of

the metallicity gradient in the bulge. A metallicity gradient is indeed

visible in the bulge when observing further away from the plane than

Baade's Window (Frogel et al.

1999 and Paper I), while in the inner regions (

![]() )

no gradient in metallicity has been found (Ramírez

et al. 2000; and Rich

et al. 2007). This can be understood if the bar as

well as the old spheroid population are both present in the inner

regions, leading to a constant metallicity at

)

no gradient in metallicity has been found (Ramírez

et al. 2000; and Rich

et al. 2007). This can be understood if the bar as

well as the old spheroid population are both present in the inner

regions, leading to a constant metallicity at

![]() ,

while the bar influence gradually fades further away from the plane

than Baade's Window. At high latitudes only the old spheroid remains:

the mean metallicity of the outer bulge measured by Ibata & Gilmore (1995)

of [Fe/H

,

while the bar influence gradually fades further away from the plane

than Baade's Window. At high latitudes only the old spheroid remains:

the mean metallicity of the outer bulge measured by Ibata & Gilmore (1995)

of [Fe/H![]() dex

corresponds very well to our metal-poor population. This scenario is

also consistent with the distribution of bulge globular clusters of Valenti et al. (2009)

who found no evidence for a metallicity gradient but all their clusters

with [Fe/H]>-0.5 dex are located within (

dex

corresponds very well to our metal-poor population. This scenario is

also consistent with the distribution of bulge globular clusters of Valenti et al. (2009)

who found no evidence for a metallicity gradient but all their clusters

with [Fe/H]>-0.5 dex are located within (

![]() ).

).

Concerning the age of the two populations, we expect the

spheroid component to be old, while the pseudo-bulge component may

contain both the old stars of the inner disc redistributed by the bar

and younger stars whose formation has been triggered by the bar gas

flow. van Loon

et al. (2003) found that although the bulk of the

bulge population is old, a fraction of the stars are of intermediate

age (1 to 7 Gyr). Groenewegen

& Blommaert (2005) observed Mira stars of ages 1-3

Gyr at all latitudes from -1.2 to -5.8 in the OGLE-II data.

Uttenthaler et al. (2007)

found four bulge stars with ages lower than 3 Gyr at a

latitude of ![]() .

Bensby et al. (2010)

found three microlensed bulge dwarfs with ages lower than

5 Gyr. 87% of the variable stars detected by Kouzuma & Yamaoka (2009)

are distributed within

.

Bensby et al. (2010)

found three microlensed bulge dwarfs with ages lower than

5 Gyr. 87% of the variable stars detected by Kouzuma & Yamaoka (2009)

are distributed within

![]() ,

and most of them should be large-amplitude and long-period variables

such as Mira variables or OH/IR stars. This intermediate age population

has been shown to trace the Galactic bar (Groenewegen &

Blommaert 2005; Izumiura et al. 1995;

Kouzuma

& Yamaoka 2009; van Loon et al. 2003),

although providing a larger bar angle (

,

and most of them should be large-amplitude and long-period variables

such as Mira variables or OH/IR stars. This intermediate age population

has been shown to trace the Galactic bar (Groenewegen &

Blommaert 2005; Izumiura et al. 1995;

Kouzuma

& Yamaoka 2009; van Loon et al. 2003),

although providing a larger bar angle (![]()

![]() )

than studies based on older tracers such as red clump stars (

)

than studies based on older tracers such as red clump stars (![]()

![]() ,

Stanek

et al. 1994; Babusiaux & Gilmore 2005).

This discrepancy in the bar angle could well be explained if the old

tracers probed a mix of spheroid and bar structures, while the young

tracers only probe the bar (although biases on the longitude area

surveyed also need to be taken into account, see Nishiyama et al. 2005).

If this intermediate age population were associated to a part of the

bar component, their presence in the CMDs would decrease while going

away from the plane as the main bar component and would therefore be a

small fraction of the CMD of Zoccali

et al. (2003) at

,

Stanek

et al. 1994; Babusiaux & Gilmore 2005).

This discrepancy in the bar angle could well be explained if the old

tracers probed a mix of spheroid and bar structures, while the young

tracers only probe the bar (although biases on the longitude area

surveyed also need to be taken into account, see Nishiyama et al. 2005).

If this intermediate age population were associated to a part of the

bar component, their presence in the CMDs would decrease while going

away from the plane as the main bar component and would therefore be a

small fraction of the CMD of Zoccali

et al. (2003) at

![]() .

Clarkson et al. (2008)

obtained a proper motion decontaminated CMD with a well defined old

turn-off in an inner field (

.

Clarkson et al. (2008)

obtained a proper motion decontaminated CMD with a well defined old

turn-off in an inner field (

![]() ,

,

![]() ).

However, we would expect an intermediate age population associated with

the bar to be metal-rich, which, due to the age-metallicity degeneracy,

would imply that this population could be hidden in the CMD of Clarkson et al. (2008)

if its contribution is small enough compared to the bulk of the bulge

population. The new filter combination proposed by the ACS Bulge

Treasury Programme to break the age-metallicity-temperature degeneracy (Brown et al. 2009) should

provide new insights into this issue.

).

However, we would expect an intermediate age population associated with

the bar to be metal-rich, which, due to the age-metallicity degeneracy,

would imply that this population could be hidden in the CMD of Clarkson et al. (2008)

if its contribution is small enough compared to the bulk of the bulge

population. The new filter combination proposed by the ACS Bulge

Treasury Programme to break the age-metallicity-temperature degeneracy (Brown et al. 2009) should

provide new insights into this issue.

We note that in Baade's Window neither the kinematics nor the chemistry allow us to distinguish what we call the old spheroid to the thick disc. The mean metallicity of the solar neighbourhood thick disc is however lower (e.g. Fuhrmann 2008 derived [Fe/H] =-0.6 and [Mg/H] =-0.2) than the mean metallicity of our metal-poor population ([Fe/H]= -0.27 dex and [Mg/H]=-0.04, Paper II). Meléndez et al. (2008), Ryde et al. (2010), Bensby et al. (2010) and Alves-Brito et al. (2010) observed similarities between the metallicity of the bulge and the metallicity of thick disc stars for metal-poor stars. The sample of Ryde et al. (2010) contains 11 of our stars all with less than solar metallicity. Simulations of the formation of thick stellar discs by rapid internal evolution in unstable, gas-rich, clumpy discs (Bournaud et al. 2009) show that thick discs and classical bulges form together in a time-scale shorter than 1 Gyr, which explains the observed abundance similarities.

The coexistence of classical and pseudo bulge has been

observed in external galaxies (Prugniel et al. 2001; Erwin 2008;

Peletier

et al. 2007) and obtained by N-body

simulations (Samland

& Gerhard 2003; Athanassoula 2005). The

chemical and dynamical model of Nakasato

& Nomoto (2003) suggests the presence of two

chemically different components in the bulge as we found, one formed

quickly through the subgalactic clump merger in the proto-Galaxy, and

the other formed gradually in the inner disc. But they do not have a

bar in their model. They fitted the kinematics of Minniti (1996) well who observed

at ![]() ,

,

![]() a

decrease of

a

decrease of ![]() with metallicity, which is coherent with what we observed at

with metallicity, which is coherent with what we observed at

![]() and that Nakasato & Nomoto

(2003) defined the bulge radius as R<2 kpc.

The chemo-dynamical model of Samland

& Gerhard (2003) predicts the different

characteristics of our sample: their total bulge population contains

two stellar populations: a metal-rich population ([Fe/H]>0.17)

with [

and that Nakasato & Nomoto

(2003) defined the bulge radius as R<2 kpc.

The chemo-dynamical model of Samland

& Gerhard (2003) predicts the different

characteristics of our sample: their total bulge population contains

two stellar populations: a metal-rich population ([Fe/H]>0.17)

with [![]() /Fe]<0

associated with the bar, and an old population that formed during the

proto-galactic collapse, with a high [

/Fe]<0

associated with the bar, and an old population that formed during the

proto-galactic collapse, with a high [![]() /Fe] and a [Fe/H]

corresponding to the ``thick disc'' component. Their model also

predicts the resulting apparent metallicity gradient along the bulge

minor axis (their Fig. 13).

/Fe] and a [Fe/H]

corresponding to the ``thick disc'' component. Their model also

predicts the resulting apparent metallicity gradient along the bulge

minor axis (their Fig. 13).

Our study highlights the importance to combine metallicity to 3D-kinematic information to disentangle the different bulge populations. This approach needs to be extended to various galactic longitudes. Gaia will not only provide those, but also allow us to determine the distances (probing the different structures along the line of sight and removing distance induced biases) and work on an impressively large sample of un-contaminated bulge stars.

AcknowledgementsM.Z. and D.M. are supported by FONDAP Center for Astrophysics 15010003, the BASAL Center for Astrophysics and Associated Technologies PFB-06, the FONDECYT 1085278 and 1090213, and the MIDEPLAN MilkyWay Millennium Nucleus P07-021-F.

References

- Aguerri, J. A. L., Balcells, M., & Peletier, R. F. 2001, A&A, 367, 428 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Alard, C. 2001, A&A, 379, L44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Alcock, C., Allsman, R. A., Alves, D. R., et al. 2000, ApJ, 541, 734 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Brito, A., Melendez, J., Asplund, M., Ramirez, I., & Yong, D. 2010, A&A, 513, A35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Athanassoula, E. 2005, MNRAS, 358, 1477 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Babusiaux, C., & Gilmore, G. 2005, MNRAS, 358, 1309 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, R. A., Churchwell, E., Babler, B. L., et al. 2005, ApJ, 630, L149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bensby, T., Feltzing, S., Johnson, J. A., et al. 2010, A&A, 512, A41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz, L., & Spergel, D. N. 1991, ApJ, 379, 631 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bournaud, F., Elmegreen, B. G., & Martig, M. 2009, ApJ, 707, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. M., Sahu, K., Zoccali, M., et al. 2009, AJ, 137, 3172 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Celeux, G., & Diebolt, J. 1986, Rev. Stat. Appl., 34, 35 [Google Scholar]

- Chiba, M., & Beers, T. C. 2000, AJ, 119, 2843 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, W., Sahu, K., Anderson, J., et al. 2008, ApJ, 684, 1110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Combes, F., & Sanders, R. H. 1981, A&A, 96, 164 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Combes, F., Debbasch, F., Friedli, D., & Pfenniger, D. 1990, A&A, 233, 82 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaucouleurs, G. 1964, in The Galaxy and the Magellanic Clouds, IAU Symp., 20, 195 [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, E., Arendt, R. G., Hauser, M. G., et al. 1995, ApJ, 445, 716 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eggen, O. J., Lynden-Bell, D., & Sandage, A. R. 1962, ApJ, 136, 748 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, P. 2008, in IAU Symposium, ed. M. Bureau, E. Athanassoula, & B. Barbuy, IAU Symp., 245, 113 [Google Scholar]

- Feltzing, S., & Gilmore, G. 2000, A&A, 355, 949 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Feltzing, S., & Johnson, R. A. 2002, A&A, 385, 67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, F. R., Dalessandro, E., Mucciarelli, A., et al. 2009, Nature, 462, 483 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frogel, J. A., Tiede, G. P., & Kuchinski, L. E. 1999, AJ, 117, 2296 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, K. 2008, MNRAS, 384, 173 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright, J. P., McWilliam, A., & Rich, R. M. 2006, ApJ, 636, 821 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright, J. P., McWilliam, A., & Rich, R. M. 2007, ApJ, 661, 1152 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fux, R. 1999, A&A, 345, 787 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen, M. A. T., & Blommaert, J. A. D. L. 2005, A&A, 443, 143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Habing, H. J., Sevenster, M. N., Messineo, M., van de Ven, G., & Kuijken, K. 2006, A&A, 458, 151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, V., Lecureur, A., Gómez, A., et al. 2010, A&A, submitted, Paper III [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. D., Rich, R. M., Reitzel, D. B., et al. 2008, ApJ, 688, 1060 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. D., Rich, R. M., Clarkson, W., et al. 2009, ApJ, 702, L153 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata, R. A., & Gilmore, G. F. 1995, MNRAS, 275, 605 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiura, H., Deguchi, S., Hashimoto, O., et al. 1995, ApJ, 453, 837 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kormendy, J., & Kennicutt, Jr., R. C. 2004, ARA&A, 42, 603 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzuma, S., & Yamaoka, H. 2009, AJ, 138, 1508 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koz▯owski, S., Wozniak, P. R., Mao, S., et al. 2006, MNRAS, 370, 435 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijken, K., & Rich, R. M. 2002, AJ, 124, 2054 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lecureur, A., Hill, V., Zoccali, M., et al. 2007, A&A, 465, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- López-Corredoira, M., Cabrera-Lavers, A., Mahoney, T. J., et al. 2007, AJ, 133, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, S., & Paczynski, B. 2002, MNRAS, 337, 895 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, A., & Rich, R. M. 1994, ApJS, 91, 749 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez, J., Asplund, M., Alves-Brito, A., et al. 2008, A&A, 484, L21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, R. M. 1996, in Barred Galaxies, ed. R. Buta, D. A. Crocker, & B. C. Elmegreen (San Francisco: ASP), IAU Colloq., 157, 179 [Google Scholar]

- Minniti, D. 1996, ApJ, 459, 579 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasato, N., & Nomoto, K. 2003, ApJ, 588, 842 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, S., Nagata, T., Baba, D., et al. 2005, ApJ, 621, L105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, M. 1999, ApJ, 514, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, C. A., Sellwood, J. A., & Hasan, H. 1996, ApJ, 462, 114 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ortolani, S., Renzini, A., Gilmozzi, R., et al. 1995, Nature, 377, 701 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peletier, R. F., Falcón-Barroso, J., Bacon, R., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 379, 445 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prugniel, P., Maubon, G., & Simien, F. 2001, A&A, 366, 68 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A., Kawata, D., Brook, C. B., & Gibson, B. K. 2010, MNRAS, 401, 1826 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, S. V., Stephens, A. W., Frogel, J. A., & DePoy, D. L. 2000, AJ, 120, 833 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala, N., Williams, T. B., & Stanek, K. Z. 2009, ApJ, 691, 1387 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rattenbury, N. J., Mao, S., Debattista, V. P., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 1165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rich, R. M., Origlia, L., & Valenti, E. 2007, ApJ, 665, L119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Robin, A. C., Reylé, C., Derrière, S., & Picaud, S. 2003, A&A, 409, 523 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Royer, F., Blecha, A., North, P., et al. 2002, in SPIE Conf. Ser., 4847, ed. J.-L. Starck, & F. D. Murtagh, 184 [Google Scholar]

- Ryde, N., Gustafsson, B., Edvardsson, B., et al. 2010, A&A, 509, A20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, E. M., Rich, R. M., & Terndrup, D. M. 1996, AJ, 112, 171 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salaris, M., & Girardi, L. 2002, MNRAS, 337, 332 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Samland, M., & Gerhard, O. E. 2003, A&A, 399, 961 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, R., Walker, A., & Cropper, M. 1990, MNRAS, 246, 54 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, M., Rich, R. M., & Kuijken, K. 2007, ApJ, 665, L31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spaenhauer, A., Jones, B. F., & Whitford, A. E. 1992, AJ, 103, 297 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek, K. Z., Mateo, M., Udalski, A., et al. 1994, ApJ, 429, L73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi, T. 2004, MNRAS, 349, 193 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi, T., Wu, X., Udalski, A., et al. 2004, MNRAS, 348, 1439 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Terndrup, D. M., Sadler, E. M., & Rich, R. M. 1995, AJ, 110, 1774 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Uttenthaler, S., Hron, J., Lebzelter, T., et al. 2007, A&A, 463, 251 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, E., Ferraro, F. R., & Origlia, L. 2009, MNRAS, 402, 1729 [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, J. T., Gilmore, G. F., Omont, A., et al. 2003, MNRAS, 338, 857 [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, K., Casetti-Dinescu, D. I., Méndez, R. A., et al. 2007, AJ, 134, 1432 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. S. 1996, MNRAS, 283, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H., Spergel, D. N., & Rich, R. M. 1994, AJ, 108, 2154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H., Rich, R. M., & Biello, J. 1996, ApJ, 470, 506 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccali, M., Renzini, A., Ortolani, S., et al. 2003, A&A, 399, 931 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccali, M., Lecureur, A., Barbuy, B., et al. 2006, A&A, 457, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]