| Issue |

A&A

Volume 507, Number 1, November III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 433 - 439 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912028 | |

| Published online | 27 August 2009 | |

A&A 507, 433-439 (2009)

Submillimeter and X-ray observations of an X class flare

C. G. Giménez de Castro1 - G. Trottet2 - A. Silva-Valio1 - S. Krucker3 - J. E. R. Costa4 - P. Kaufmann1,5 - E. Correia1,4 - H. Levato6

1 - Centro de Rádio Astronomia e Astrofísica Mackenzie, R.

da Consolação 896, 01302-907, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

,

2 - LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Section de Meudon, 92195 Meudon,

France

3 - Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, USA

4 - Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, São José dos Campos,

Brazil

5 - Centro de Componentes Semicondutores, Universidade Estadual de

Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

6 - Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito, CONICET, San Juan, Argentina

Received 10 March 2009 / Accepted 7 July 2009

Abstract

The GOES X1.5 class flare that occurred on August 30, 2002 at

1327:30 UT is one of the few events detected so far at

submillimeter wavelengths. We present a detailed analysis of this flare

combining radio observations from 1.5 to 212 GHz (an upper

limit

of the flux is also provided at 405 GHz) and X-ray. Although

the

observations of radio emission up to 212 GHz indicates that

relativistic electrons with energies of a few MeV were

accelerated, no significant hard X-ray emission was detected by RHESSI

above ![]() 250 keV.

Images at 12-20 and 50-100 keV reveal a very compact, but

resolved, source of about

250 keV.

Images at 12-20 and 50-100 keV reveal a very compact, but

resolved, source of about ![]()

![]() .

EUV TRACE images show a multi-kernel structure suggesting a complex

(multipolar) magnetic

topology. During the peak time the radio spectrum shows an extended

flatness from

.

EUV TRACE images show a multi-kernel structure suggesting a complex

(multipolar) magnetic

topology. During the peak time the radio spectrum shows an extended

flatness from ![]() 7

to 35 GHz. Modeling the optically thin part of the

radio spectrum as gyrosynchrotron emission we obtained the electron

spectrum (spectral index

7

to 35 GHz. Modeling the optically thin part of the

radio spectrum as gyrosynchrotron emission we obtained the electron

spectrum (spectral index ![]() ,

instantaneous number of emitting

electrons). It is shown that in order to keep the expected X-ray

emission from the same emitting electrons below the RHESSI background

at 250 keV, a magnetic field above 500 G is

necessary. On the

other hand, the electron spectrum deduced from radio observations

,

instantaneous number of emitting

electrons). It is shown that in order to keep the expected X-ray

emission from the same emitting electrons below the RHESSI background

at 250 keV, a magnetic field above 500 G is

necessary. On the

other hand, the electron spectrum deduced from radio observations ![]() 50 GHz

is harder than that deduced from

50 GHz

is harder than that deduced from ![]() 70-250 keV

X-ray data, meaning that there must exist a breaking energy around a

few hundred keV. During the decay of the

impulsive phase, a hardening of the X-ray spectrum is observed which is

interpreted as a hardening of the electron distribution spectrum

produced by the diffusion due to Coulomb collisions of the trapped

electrons in a medium

with an electron density of

70-250 keV

X-ray data, meaning that there must exist a breaking energy around a

few hundred keV. During the decay of the

impulsive phase, a hardening of the X-ray spectrum is observed which is

interpreted as a hardening of the electron distribution spectrum

produced by the diffusion due to Coulomb collisions of the trapped

electrons in a medium

with an electron density of

![]() .

.

Key words: Sun: activity - Sun: flares - Sun: radio radiation - Sun: X-rays, gamma rays - Sun: particle emission

1 Introduction

During solar flares, a fraction of the released energy is used to

accelerate

electrons with energies well above 1 MeV. The interaction of these

particles with the magnetic field of the flaring region produces

gyrosynchrotron / synchrotron radiation observed at cm or smaller

wavelengths (see e.g. Pick

& Vilmer 2008; Bastian

et al. 1998, for

reviews) and a bremsstrahlung continuum

caused by Coulomb collisions observed with X- and ![]() -ray

detectors. It was shown (e.g. Kundu

et al. 1994) that the electron

spectrum N(E) determined by

means of

-ray

detectors. It was shown (e.g. Kundu

et al. 1994) that the electron

spectrum N(E) determined by

means of ![]() 30 GHz

radio observations is

harder than that deduced from Hard X-ray (HXR) below a few hundred keV.

However for a few events, the electron spectra were found consistent

with

spectra inferred from

30 GHz

radio observations is

harder than that deduced from Hard X-ray (HXR) below a few hundred keV.

However for a few events, the electron spectra were found consistent

with

spectra inferred from ![]() -ray

continuum above

-ray

continuum above ![]() 1 MeV

(Trottet

et al. 1998,2000).

Since radio emission above 30 GHz is produced mainly by

electrons of a few MeV (see

e.g. Ramaty

et al. 1994; White

& Kundu 1992), these results have an impact on

acceleration mechanism models, which are still, an open question in

solar

flare theory, and reinforces the need for good diagnostics of the

>1 MeV particles.

1 MeV

(Trottet

et al. 1998,2000).

Since radio emission above 30 GHz is produced mainly by

electrons of a few MeV (see

e.g. Ramaty

et al. 1994; White

& Kundu 1992), these results have an impact on

acceleration mechanism models, which are still, an open question in

solar

flare theory, and reinforces the need for good diagnostics of the

>1 MeV particles.

Continuum X- and ![]() -ray

detectors may observe photons from a few keV

up to tens of MeV, but have as a limitation the low

sensitivity and / or

high background in the high energy range. In the past three solar

cycles

only a few tens of flares have been observed above 1 MeV. On

the other

hand, radioastronomy at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths is

more

efficient than the

-ray

detectors may observe photons from a few keV

up to tens of MeV, but have as a limitation the low

sensitivity and / or

high background in the high energy range. In the past three solar

cycles

only a few tens of flares have been observed above 1 MeV. On

the other

hand, radioastronomy at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths is

more

efficient than the ![]() -ray

detectors. Routine solar flare observations

at 212 and 405 GHz started in March 2001 with the

Solar Submillimeter

Telescope (SST, Kaufmann

et al. 2001), installed in the Argentinean

Andes. A few flares were also observed at 210, 230, and

345 GHz with a

receiver array installed at the focus of the Köln Observatory for

Submillimeter and Millimeter Astronomy (KOSMA) telescope

(Lüthi

et al. 2004a,b).

The first observations using such

instruments showed that the spectrum above 100 GHz is a

continuation of the

cm-wavelength optically thin spectrum

(e.g. Trottet

et al. 2002; Lüthi

et al. 2004b) and extended the

diagnostic tools of radio observations to higher energy (a few tens of

MeV)

electrons. However, an unexpected upturn of the spectrum above

100 GHz was

reported for other

-ray

detectors. Routine solar flare observations

at 212 and 405 GHz started in March 2001 with the

Solar Submillimeter

Telescope (SST, Kaufmann

et al. 2001), installed in the Argentinean

Andes. A few flares were also observed at 210, 230, and

345 GHz with a

receiver array installed at the focus of the Köln Observatory for

Submillimeter and Millimeter Astronomy (KOSMA) telescope

(Lüthi

et al. 2004a,b).

The first observations using such

instruments showed that the spectrum above 100 GHz is a

continuation of the

cm-wavelength optically thin spectrum

(e.g. Trottet

et al. 2002; Lüthi

et al. 2004b) and extended the

diagnostic tools of radio observations to higher energy (a few tens of

MeV)

electrons. However, an unexpected upturn of the spectrum above

100 GHz was

reported for other ![]() M

class events (e.g. Kaufmann

et al. 2004; Lüthi

et al. 2004a; Cristiani

et al. 2008). The

physical processes responsible for the production of the spectrum

upturn

are still unknown and are a subject of debate

(Trottet

et al. 2008; Silva

et al. 2007; Kaufmann

& Raulin 2006).

M

class events (e.g. Kaufmann

et al. 2004; Lüthi

et al. 2004a; Cristiani

et al. 2008). The

physical processes responsible for the production of the spectrum

upturn

are still unknown and are a subject of debate

(Trottet

et al. 2008; Silva

et al. 2007; Kaufmann

& Raulin 2006).

In this paper, we present a combined analysis of the impulsive phase of the August 30, 2002, X class flare using RHESSI X-ray observations and spatially unresolved radio data covering the range between 1.5 to 212 GHz (and an upper limit for 405 GHz) obtained by different instruments. The event has been analyzed by different authors. Karlický et al. (2004) related radio observations between 0.8 and 2.0 GHz and X-ray spectra and images from RHESSI. They found high-frequency drifting structures between 1327:38 and 1327:50 UT with a global drift of -25 MHz s-1. The 10-20 keV X-ray sources show a north-east displacement with a projected velocity of about 10 km s-1, while the 29-44 keV emission is delayed by about 0.5 to 0.7 s after the radio drifting structure. Microwave observations of a short pulse during the onset of this event was analyzed by Giménez de Castro et al. (2006) who found a strikingly narrow spectrum that was explained as gyrosynchrotron emission of accelerated electrons with a maximum energy (high energy cutoff) of about 250 keV. Another event with similar properties was qualitatively discussed by Lüthi et al. (2004b). In this work we extend the analysis of Giménez de Castro et al. (2006) to the entire event. Moreover, we perform a quantitative analysis of the data which allows us to estimate the characteristics of the emitting electrons (energy spectrum, total number) and of the flaring region (density, magnetic field strength) that are necessary to account for the apparent discrepancy between X-ray and radio observations.

2 Instrumentation

The hard X-ray (HXR) and radio data used in the present analysis of the August 30, 2002 event were obtained with the NASA Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), the Solar Submillimeter Telescope (SST, installed in the Argentinean Andes), the nulling interferometer and patrol telescopes of the University of Bern (Switzerland), the Radio Solar Telescope Network (RSTN), and the Solar Radio-polarimeter of the Radio Observatory of Itapetinga (ROI, Brazil).

RHESSI provides imaging and spectral HXR/![]() -ray observations, with

high spatial (

-ray observations, with

high spatial (![]() 2 arcsec)

and spectral (

2 arcsec)

and spectral (![]() 1 keV)

resolution in

the

1 keV)

resolution in

the ![]() 3 keV-17 MeV

energy range (Lin & et

al. 2002).

3 keV-17 MeV

energy range (Lin & et

al. 2002).

The SST (Kaufmann

et al. 2000) operates simultaneously at 212 and

405 GHz and with a time resolution of 1 ms for the

present event. The focal

system consists of four receivers at 212 GHz and two at

405 GHz. At 212 GHz

this produces a cluster of beams that, in principle, allows us to

determine the centroid of the emitting region whenever an event is

detected

(see Giménez

de Castro et al. 1999, and references therein for

details). During the

August 30, 2002 flare, SST was tracking NOAA

region 10095, with one of the

two 405 GHz beams pointing at the active region. At

212 GHz, the event

was observed with only one beam so that it was not possible to estimate

the

centroid position of the emitting region. The antenna temperatures have

been corrected for atmospheric attenuation (zenith optical depth

![]() nepers and

nepers and ![]() nepers) and converted to

flux density assuming that: (i) the source is much smaller

than the

beam size and; (ii) there is no important main-lobe gain

correction

due to a possible offset pointing. Since the HPBW of the beams are

respectively

nepers) and converted to

flux density assuming that: (i) the source is much smaller

than the

beam size and; (ii) there is no important main-lobe gain

correction

due to a possible offset pointing. Since the HPBW of the beams are

respectively ![]() 4

4

![]() and

2

and

2

![]() at 212 and 405 GHz,

hypothesis (i) is justified here, because this event is very

compact

in the HXR domain (see Sect. 3.2).

On the other hand,

the projected position of the beam that observed the burst in the sky

is

separated by less than 30

at 212 and 405 GHz,

hypothesis (i) is justified here, because this event is very

compact

in the HXR domain (see Sect. 3.2).

On the other hand,

the projected position of the beam that observed the burst in the sky

is

separated by less than 30

![]() from the HXR emitting region observed by

RHESSI. As this is comparable to the absolute position uncertainty of

the

SST antenna, hypothesis; (ii) is also justified. It should be

emphasized that a misalignment of 30

from the HXR emitting region observed by

RHESSI. As this is comparable to the absolute position uncertainty of

the

SST antenna, hypothesis; (ii) is also justified. It should be

emphasized that a misalignment of 30

![]() produces a main-lobe gain

correction of less than 5% at 212 GHz (

produces a main-lobe gain

correction of less than 5% at 212 GHz (

![]() ).

).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12028-01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg14.png)

|

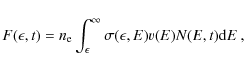

Figure 1: Time evolution of the August 30, 2002 flare, at different radio frequencies and in selected SXR and HXR energy channels. At 89.4 and 212 GHz the dashed curve represents the computed contribution of an isothermal source. A, B, and C indicate, respectively, characteristic time bins around the maximum of the HXR emission, the maximum of the 212 GHz radiation, and the decay phase of the burst. Horizontal bars denote the time intervals I through IV (see text). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The two-element nulling interferometer of the University of Bern

provides

total flux measurements at 89.4 GHz with a sensitivity of ![]() 35 s.f.u.

(1 s.f.u. = 10-22 W m-2 Hz-1)

and a time resolution

of 31 ms (Lüthi

et al. 2004b). Total flux densities at 11.8, 19.6,

35,

and 50 GHz were recorded by the patrol telescopes at Bumishus

(Switzerland)

with a time resolution of 100 ms. Total flux density

measurements made at

1.415, 2.695, 4.995, 8.8, and 15.4 GHz by the RSTN with a time

resolution

of 1 s, and at 7 GHz by the Solar Radio-polarimeter

of the Radio

Observatory of Itapetinga with 20 ms time resolution have also

been used.

35 s.f.u.

(1 s.f.u. = 10-22 W m-2 Hz-1)

and a time resolution

of 31 ms (Lüthi

et al. 2004b). Total flux densities at 11.8, 19.6,

35,

and 50 GHz were recorded by the patrol telescopes at Bumishus

(Switzerland)

with a time resolution of 100 ms. Total flux density

measurements made at

1.415, 2.695, 4.995, 8.8, and 15.4 GHz by the RSTN with a time

resolution

of 1 s, and at 7 GHz by the Solar Radio-polarimeter

of the Radio

Observatory of Itapetinga with 20 ms time resolution have also

been used.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12028-02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg15.png)

|

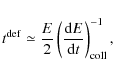

Figure 2: Background subtracted count rate spectra measured by RHESSI (error bars) during time bins A, B, and C marked in Fig. 1. The asterisks show the background spectrum. The continuous lines show the best fit models (see text). The vertical dashed lines indicate the fitted energy range. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Observations and data analysis

The August 30, 2002 HXR and radio event starting at ![]() 1327:30 UT

is

associated with a GOES X1.5 SXR burst and, with a surprisingly small,

H

1327:30 UT

is

associated with a GOES X1.5 SXR burst and, with a surprisingly small,

H![]() sub-flare which occurred in NOAA Active Region 10095 (N15

E74). This event was observed by RHESSI up to

sub-flare which occurred in NOAA Active Region 10095 (N15

E74). This event was observed by RHESSI up to ![]() 250 keV around its

maximum and in a large part of the radio spectrum ranging from

submillimeter to decameter and longer wavelengths. Figure 1

displays the time profile of the event in the 100-150 keV HXR

band, in the SXR 1-8 Å channel; it also shows the total flux

densities at 11.8, 89.4, and 212 GHz. The flare comprises an

impulsive

phase that starts at

250 keV around its

maximum and in a large part of the radio spectrum ranging from

submillimeter to decameter and longer wavelengths. Figure 1

displays the time profile of the event in the 100-150 keV HXR

band, in the SXR 1-8 Å channel; it also shows the total flux

densities at 11.8, 89.4, and 212 GHz. The flare comprises an

impulsive

phase that starts at ![]() 1327:40 UT

in the 100-150 keV band and which

lasts for about 60 s.

1327:40 UT

in the 100-150 keV band and which

lasts for about 60 s.

3.1 Flux and spectra

3.1.1 Hard X-rays

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12028-03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg16.png)

|

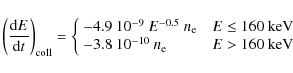

Figure 3:

From top to bottom: time evolution of the HXR

spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Spectral analysis of RHESSI data was performed between 1327:28

and

1328:36 UT. Count rate spectra were accumulated between

1327:38

and

1327:44 UT (before the thick shutter came in) and in all 4

second

intervals

between 1327:52 and 1328:32 UT using front detectors

1, 3-6,

8 and 9. We

applied pile up and decimation corrections. Each spectra consists of

77 energy bands between 3 and 250 keV. For each

interval,

spectral fitting was

carried out for energies ranging from 40 keV to the highest

energy

where

count rates in excess of 2![]() above background are measured. It is

found that the count rate spectra could be reasonably represented by

considering either a single power law or a double power-law. In the

latter

case, the break energy lies around 70 keV. Since we are

interested

in the

non-thermal X-ray emission, we have restricted the analysis to the

energies above 70 keV using a single power-law of spectral

index

above background are measured. It is

found that the count rate spectra could be reasonably represented by

considering either a single power law or a double power-law. In the

latter

case, the break energy lies around 70 keV. Since we are

interested

in the

non-thermal X-ray emission, we have restricted the analysis to the

energies above 70 keV using a single power-law of spectral

index ![]() for the trial photon spectra. Figure 2 displays

examples of the fitted spectra for the time bins labeled A, B, and C in

Fig. 1.

The time evolution of

for the trial photon spectra. Figure 2 displays

examples of the fitted spectra for the time bins labeled A, B, and C in

Fig. 1.

The time evolution of ![]() is shown in Fig. 3.

is shown in Fig. 3.

3.1.2 Radio

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12028-04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg18.png)

|

Figure 4: The radio spectrum at instants labeled A, B, and C. (see Fig. 1) Solid curves represent the homogeneous gyrosynchrotron solution fits discussed in Sect. 4.3. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

At frequencies above 20 GHz there is a time extended emission

that lasts

for tens of minutes after the impulsive phase (see Fig. 1

at 89.4 and 212 GHz). This gradual component is most likely of

thermal

origin because it seems to follow the SXR emission from GOES and has no

HXR

counterpart. The comparison of the >20 GHz time

evolution with that of

the 1-8 Å SXR indicates that this thermal component may have

started

at the beginning of the impulsive phase and therefore should be

subtracted

from the total flux densities in order to estimate the non thermal

emission

of the radio burst. For this we consider that the thermal emission

arises

from the hot thermal source that produces the SXR emission observed by

GOES. We computed the free-free flux density of an isothermal source

with

temperature and emission measure (EM) derived from GOES 8

observations. A

source size of 60

![]() provides a reasonable agreement with the observations

as illustrated in Fig. 1

(dot-dash lines at 89.4 and 212 GHz curves). Figure 4 shows

the non-thermal radio spectrum

for the three time bins marked A, B and C in Fig. 1 that

correspond, respectively, to the maximum of the 100-150 keV

emission, to the

maximum of the 212 GHz, and to the decay of the impulsive

phase. The main

characteristics of the radio spectra can be summarized as follows:

provides a reasonable agreement with the observations

as illustrated in Fig. 1

(dot-dash lines at 89.4 and 212 GHz curves). Figure 4 shows

the non-thermal radio spectrum

for the three time bins marked A, B and C in Fig. 1 that

correspond, respectively, to the maximum of the 100-150 keV

emission, to the

maximum of the 212 GHz, and to the decay of the impulsive

phase. The main

characteristics of the radio spectra can be summarized as follows:

- from 1 to 7 GHz:

- the spectrum increases with frequency and can be

represented by a power law with spectral index

1;

1; - from 7 to 35 GHz:

- there is a plateau observed during the impulsive phase (Fig. 4A, B). During the decay of the impulsive phase the spectrum gradually evolves exhibiting a rather well defined turnover frequency around 5 GHz (Fig. 4C);

- above 50 GHz:

- the flux density is roughly proportional to

.

Figure 3

shows the time evolution of

.

Figure 3

shows the time evolution of  .

.

3.2 HXR images

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12028-05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg21.png)

|

Figure 5: RHESSI emitting regions of 50-100 keV (solid contours) and of 12-20 keV (dashed contours) for different time intervals superimposed on a negative 195 Å image taken by TRACE at 1327:31 UT. Contour levels are: 50, 70, 90, and 99% of the image maximum. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 5

displays RHESSI contours in the 12-20 keV and

50-100 keV bands overlaid on a 195 Å TRACE image

taken at 1327:31 UT

for the four intervals marked by horizontal bars in Fig. 1.

Intervals I and II cover the first two

100-150 keV

peaks, interval III spreads over the maximum of the 212 GHz,

while

interval IV extends over the HXR decay phase. RHESSI images were

obtained

by applying the PIXON algorithm (Metcalf

et al. 1996) and by using front

detector segments 1 to 6. Detector 2 was not used for the

12-20 keV

images. The TRACE image was taken close to the onset of the radio and

HXR

impulsive peaks. The figure shows that the impulsive phase of the flare

was

triggered within a complex pattern of bright EUV features in a compact

region

(10

![]()

![]() 10

10

![]() ).

Unfortunately, subsequent 195 Å TRACE

images are saturated until 1350 UT. During

intervals I and

II, the 50-100 keV emission (solid contours) arises from two

compact regions (

).

Unfortunately, subsequent 195 Å TRACE

images are saturated until 1350 UT. During

intervals I and

II, the 50-100 keV emission (solid contours) arises from two

compact regions (![]() 3-7

3-7

![]() )

overlaying bright EUV structures. During the rest of the event

(intervals III to IV), only the southeast source is observed

at

50-100 keV. During the whole event the lower energy HXR

(12-20 keV, dashed

contours) arise predominantly from a single source close to the

southeast

of the 50-100 keV emitting region. However, the interpretation

of

the HXR images at 50 keV for interval III

and IV is

inconclusive as up to half of the counts are due to pile up of thermal

photons. To correct pile up in images is very difficult as the

corrections should be done in the modulated light curves. Currently,

the RHESSI software does not provide pile up correction in images.

)

overlaying bright EUV structures. During the rest of the event

(intervals III to IV), only the southeast source is observed

at

50-100 keV. During the whole event the lower energy HXR

(12-20 keV, dashed

contours) arise predominantly from a single source close to the

southeast

of the 50-100 keV emitting region. However, the interpretation

of

the HXR images at 50 keV for interval III

and IV is

inconclusive as up to half of the counts are due to pile up of thermal

photons. To correct pile up in images is very difficult as the

corrections should be done in the modulated light curves. Currently,

the RHESSI software does not provide pile up correction in images.

4 Discussion

EUV observations close to the onset of the impulsive phase of the

August

30, 2002 event reveal that this flare arose from a compact region with

a

multi kernel structure that suggests a complex (multipolar) magnetic

field

topology. The HXR emitting sources are observed in association with

different EUV bright structures, suggesting that they are located at

the

footpoints of different magnetic loops (see Fig. 5). The

compactness of this flare is further supported by the fact that such an

X class event produced only an H![]() sub-flare. In the following, we

discuss some peculiarities of this HXR and radio event:

sub-flare. In the following, we

discuss some peculiarities of this HXR and radio event:

- the unusually flat radio spectrum between 7 and 35 GHz during most of the impulsive phase (intervals I to III on Fig. 1);

- the lack of significant

ray emission detected by RHESSI in the MeV domain, although

ray emission detected by RHESSI in the MeV domain, although  90 GHz

radio data indicate that relativistic electrons were produced during

the flare;

90 GHz

radio data indicate that relativistic electrons were produced during

the flare; - the strong hardening of the >70 keV HXR spectrum during the decay of the impulsive phase.

- during intervals I and II, the 100-150 keV emission is consistent with thick-target emission because it arises predominantly from footpoint sources. Furthermore there is no long-term coronal trapping because the HXR peaks occur simultaneously at all energies within the RHESSI time resolution (4 s). Thus, the time evolution of the HXR emission mimics that of the electron injection into the thick-target region;

- taking into account the above arguments, interval III corresponds to a third injection which is reflected by the shoulder in the 100-150 keV time profile range and corresponds to the maximum of the 212 GHz emission;

- the hardening of the HXR spectrum during interval IV may be indicative of some trapping.

4.1 The flat radio spectrum

It is well documented that cm-mm emission comes from gyrosynchrotron radiation of energetic relativistic electrons propagating in the magnetic structures (e.g. Pick & Vilmer 2008, and references therein). The radio spectra of the present event are indeed reminiscent of this emission process. In a uniform magnetic field, the emission would lead to a spectral index larger than 2.5 in the optically thick region and a rather well defined turnover frequency. However, the spectral index for the frequency range 1-7 GHz (optically thick emission) remains around or below 1 during the whole event. And until the decay of the impulsive phase (interval IV) the radio spectrum is flat between 7 and 35 GHz (see Fig. 4). Both these characteristics are indications that radio emitting electrons propagate in a highly inhomogeneous magnetic field (e.g. Klein et al. 1986; Lee et al. 1994; Dulk 1985). This inhomogeneous magnetic field interpretation is consistent with the complex magnetic structure revealed by TRACE and RHESSI images. During the decay of the impulsive phase, a well defined turnover frequency gradually becomes better defined. At the same time, the X-ray emission arises from a single source, so that the observed radio spectrum is closer to that expected from a homogeneous source.

Ramaty

& Petrosian (1972) explained flat microwave spectra

as observed

by Hachenberg

& Wallis (1961) by including the free-free absorption

of a cold

medium uniformly mixed in the homogeneous gyrosynchrotron source

region.

Indeed: (i) at low frequencies, where both gyrosynchrotron and

free-free

opacities are >1, the radio flux increases with frequency;

(ii) at

frequencies for which the gyrosynchrotron opacity is <1 while

the free-free

opacity remains >1, a plateau is observed because while the

gyrosynchrotron emission starts to decrease the free-free emission is

still

increasing; (iii) at higher frequencies both emissions are optically

thin and

the radio spectrum decreases with frequency.

The observation of simultaneous brightenings and line broadening of

hot (![]() 107 K)

and cold (

107 K)

and cold (![]() 104 K)

plasmas during a solar limb

flare (Kliem

et al. 2002) provides some support to the Ramaty

&

Petrosian hypothesis. In addition to magnetic field inhomogeneities,

free-free absorption may also contribute to provide the observed flat

radio

spectrum. In that case, as the flare evolves, the free-free opacity

should

decrease in order to allow lower frequency radiation to become

optically

thin. Since free-free opacity is proportional to

104 K)

plasmas during a solar limb

flare (Kliem

et al. 2002) provides some support to the Ramaty

&

Petrosian hypothesis. In addition to magnetic field inhomogeneities,

free-free absorption may also contribute to provide the observed flat

radio

spectrum. In that case, as the flare evolves, the free-free opacity

should

decrease in order to allow lower frequency radiation to become

optically

thin. Since free-free opacity is proportional to ![]() (

(

![]() medium density and temperature, respectively, and assuming

medium density and temperature, respectively, and assuming ![]() ),

this would imply either a decrease of the density, or an increase of

the temperature, or an increase of both. In the latter case the

temperature

should increase faster than the density.

),

this would imply either a decrease of the density, or an increase of

the temperature, or an increase of both. In the latter case the

temperature

should increase faster than the density.

Above 50 GHz (optically thin emission), the radiation, which

is mostly emitted

by highly relativistic electrons, is not affected by

the medium, and the spectral radio index ![]() is only related to the

index of the instantaneous electron distribution

is only related to the

index of the instantaneous electron distribution ![]() .

For the present

event

.

For the present

event ![]() remains between 1.1 and 1.3 (Fig. 3).

Considering the ultra-relativistic case as a gross approximation, this

leads to

remains between 1.1 and 1.3 (Fig. 3).

Considering the ultra-relativistic case as a gross approximation, this

leads to ![]() (Dulk 1985).

(Dulk 1985).

4.2 HXR spectral hardening during the decay of the impulsive phase

During interval IV the HXR spectral index ![]() decreases from 4.1 to 2.8

(Fig. 3).

This provides some indication that a significant

amount of HXR was produced by trapped electrons, the diffusion rate

being

governed by Coulomb collisions. For the weak-diffusion limit case, the

trapping time

decreases from 4.1 to 2.8

(Fig. 3).

This provides some indication that a significant

amount of HXR was produced by trapped electrons, the diffusion rate

being

governed by Coulomb collisions. For the weak-diffusion limit case, the

trapping time ![]() ,

with

,

with ![]() the characteristic deflection time, which is given by Trubnikov (1965)

and

Melrose

& Brown (1976)

the characteristic deflection time, which is given by Trubnikov (1965)

and

Melrose

& Brown (1976)

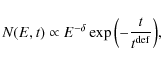

|

(1) |

where

|

(2) |

with E the electron energy in keV and

We consider that the injection of electrons in the HXR

emitting region

stopped at 1328:14 UT because it is the last time bin where ![]() remains

almost constant (see Fig. 3). Under

these conditions

the time evolution of the distribution of the trapped electrons is

approximately given by (Aschwanden 1998)

remains

almost constant (see Fig. 3). Under

these conditions

the time evolution of the distribution of the trapped electrons is

approximately given by (Aschwanden 1998)

|

(3) |

with

where v(E) is the electron velocity corresponding to energy E,

Spectral hardening has been reported during the impulsive phase of long duration GOES X class flares and associated with non thermal footpoint bremsstrahlung (Qiu et al. 2004; Saldanha et al. 2008). Grigis & Benz (2008) analyzed the spectral hardening during the gradual phase of great flares and concluded that the cause is the continuing acceleration with longer trapping in the accelerator before escape. Kiplinger (1995) has shown that the hardening is associated with SEP events.

4.3 Relationship between HXR and radio emission

The absence of HXR emission >250 keV while we observe

radio emission

above 50 GHz can be used to constrain the high energy electron

distribution, the magnetic field, and the trapping time in the radio

emitting region. For that, we consider that non thermal electrons are

injected in coronal loops. The radio emission is produced in the

coronal

portion of these loops where they become partially trapped while

precipitating electrons produce the HXR radiation by thick target

interaction at the loop footpoints. Since no spatially resolved radio

data

are available for this event and the optically thin part of the radio

spectrum does not depend on the structure details of the medium, we

used a homogeneous model to derive the mean parameters of the radio

source

and emitting electrons. For that, we computed the radio optically thin

emission by using the numerical code for a gyrosynchrotron source with

a

homogeneous ambient density and magnetic field and an isotropic

electron

distribution developed by Ramaty (1969)

and corrected by

Ramaty

et al. (1994)![]() .

The instantaneous electron

distribution in the radio source was taken as

.

The instantaneous electron

distribution in the radio source was taken as ![]() ,

where

K is the number of electrons per MeV at

1 MeV and the energy E is in

MeV. The angle between the observer and the magnetic field (view-angle)

was

set to 84

,

where

K is the number of electrons per MeV at

1 MeV and the energy E is in

MeV. The angle between the observer and the magnetic field (view-angle)

was

set to 84![]() (the maximum allowed value in Ramaty's solution) in order

to obtain the lower limit of the total number of electrons necessary to

produce a given radio spectrum for a given magnetic field strength. For

a

view-angle of 45

(the maximum allowed value in Ramaty's solution) in order

to obtain the lower limit of the total number of electrons necessary to

produce a given radio spectrum for a given magnetic field strength. For

a

view-angle of 45![]() ,

as is usually assumed, the computed number of

electrons is roughly twice that obtained for 84

,

as is usually assumed, the computed number of

electrons is roughly twice that obtained for 84![]() .

Table 1

displays the values of the instantaneous total number of electrons

above 25 keV

.

Table 1

displays the values of the instantaneous total number of electrons

above 25 keV ![]() and K obtained for different values of the

magnetic field at the maximum of the 100-150 keV HXR (time bin

A) .

and K obtained for different values of the

magnetic field at the maximum of the 100-150 keV HXR (time bin

A) . ![]() was computed for

was computed for ![]() which provides the best

fit to the radio data. This is in agreement with the value of

which provides the best

fit to the radio data. This is in agreement with the value of ![]() inferred from the slope of the optically thin part of the radio

spectrum

inferred from the slope of the optically thin part of the radio

spectrum ![]() (see Sect. 4.1).

(see Sect. 4.1).

Table

1:

Derived characteristic of radio radiating electrons for different

magnetic field strengths and view angle equal to 84![]() .

.

The mean electron flux ![]() entering the thick target HXR

source is

entering the thick target HXR

source is ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the

time spent by the electrons in the radio source. The thick target

photon emission from these precipitating electrons was calculated by

using a numerical code that takes into account both electron-proton

and electron-electron collisions. The photon spectrum is then

convolved with the RHESSI response matrix to get the corresponding

count rate spectrum. Figure 1 shows

that within the RHESSI

time resolution (4 s), the 89.4 GHz, 212 GHz

and 100-150 keV count rates show simultaneous peaks during

intervals I to III. The electron trapping time

is the

time spent by the electrons in the radio source. The thick target

photon emission from these precipitating electrons was calculated by

using a numerical code that takes into account both electron-proton

and electron-electron collisions. The photon spectrum is then

convolved with the RHESSI response matrix to get the corresponding

count rate spectrum. Figure 1 shows

that within the RHESSI

time resolution (4 s), the 89.4 GHz, 212 GHz

and 100-150 keV count rates show simultaneous peaks during

intervals I to III. The electron trapping time ![]() can thus be considered independent of energy as a first approximation.

This suggest that during intervals I to III the

precipitation rate is more likely governed by wave-particle

interactions (turbulent trapping) than by Coulomb collisions (e.g. Vilmer 1987).

The computations were then carried out for

can thus be considered independent of energy as a first approximation.

This suggest that during intervals I to III the

precipitation rate is more likely governed by wave-particle

interactions (turbulent trapping) than by Coulomb collisions (e.g. Vilmer 1987).

The computations were then carried out for ![]() ,

the lower and upper limits correspond respectively to free streaming of

the electrons in a compact loop (

,

the lower and upper limits correspond respectively to free streaming of

the electrons in a compact loop (![]() 10

10

![]() ), and to the RHESSI time

resolution. Figure 6

displays the RHESSI expected count rates in the 250-265 keV

band as a function of

), and to the RHESSI time

resolution. Figure 6

displays the RHESSI expected count rates in the 250-265 keV

band as a function of ![]() for

different values of the magnetic field. The dashed horizontal line

corresponds to the RHESSI count rate in this channel, the highest

energy where this event

was detected. We conclude that the mean magnetic field strength

should be greater than about 500 G to keep the thick target

photon

flux

expected from radio emitting electrons with trapping times smaller

than 1 s below the detection limit of RHESSI.

for

different values of the magnetic field. The dashed horizontal line

corresponds to the RHESSI count rate in this channel, the highest

energy where this event

was detected. We conclude that the mean magnetic field strength

should be greater than about 500 G to keep the thick target

photon

flux

expected from radio emitting electrons with trapping times smaller

than 1 s below the detection limit of RHESSI.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip]{12028-06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/43/aa12028-09/Timg51.png)

|

Figure 6: Expected

RHESSI

count rates at 250 keV as a function of the emitting electron

trapping time for different magnetic field strengths

and view angle equal to 84 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

It has been shown that the thick target spectral index ![]() is bounded

between

is bounded

between ![]() ,

the lower limit

corresponding to turbulent trapping of electrons with energies above a

few

100 keV, whereas the higher limit is set by free propagating

electrons with

energies below a few 100 keV (see e.g. Trottet

et al. 1998, and references

therein.). Therefore if

,

the lower limit

corresponding to turbulent trapping of electrons with energies above a

few

100 keV, whereas the higher limit is set by free propagating

electrons with

energies below a few 100 keV (see e.g. Trottet

et al. 1998, and references

therein.). Therefore if ![]() ,

the HXR emission

of these electrons should have an index between

,

the HXR emission

of these electrons should have an index between ![]() which

is significantly smaller than the observed values,

which

is significantly smaller than the observed values, ![]() 4.3, during

intervals I to III (see Fig. 3). This is

in accordance with

previous works that show that radio high frequency emission is

generated by

electrons with energies above

4.3, during

intervals I to III (see Fig. 3). This is

in accordance with

previous works that show that radio high frequency emission is

generated by

electrons with energies above ![]() 500 keV with an electron index harder

than the <500 keV electrons (Trottet

et al. 1998; Silva

et al. 2000; White &

Kundu 1992; Kundu

et al. 1994).

500 keV with an electron index harder

than the <500 keV electrons (Trottet

et al. 1998; Silva

et al. 2000; White &

Kundu 1992; Kundu

et al. 1994).

5 Summary

In this paper we have analyzed X-ray observations from RHESSI and radio data obtained at submillimeter wavelengths by the Solar Submillimeter Telescope (SST) of the X1.5 event that occurred in Active Region 10095 on August 30, 2002, at 1327:30 UT, complemented with radio observations from 1.5 to 89.4 GHz from other instruments. EUV images from TRACE provided information about the source emitting region.

The radio spectrum above 100 GHz is the continuation of the optically thin microwave spectrum, therefore does not belong to the so called THz bursts (Kaufmann et al. 2004), although it is an X Class flare. We summarize below our main findings:

- The magnetic structure of the flare is complex and highly inhomogeneous. This is revealed by the 50-100 keV and EUV images. Such an inhomogeneous source may produce the flatness in the radio spectrum observed between 7 and 35 GHz, although we do not discard the free-free absorption.

- The electron spectrum N(E) above 1 MeV is harder than that at energies below a few hundred keV.

- Modeling simultaneously the expected RHESSI count rate and the expected gyrosynchrotron emission, we obtain 500 G as a lower limit for the mean magnetic field of the flaring region.

- The time evolution of the spectral index deduced from X-ray

observations at the end of interval III suggests that trapped

electrons are diffused by Coulomb collisions. This leads to a mean

ambient electron density of

cm-3,

typical of the low corona / upper chromosphere and is compatible with

previous results (Krucker

et al. 2008) and with the small size of the EUV

pattern observed by TRACE, which also suggests that the flaring region

does not extend high in the corona.

cm-3,

typical of the low corona / upper chromosphere and is compatible with

previous results (Krucker

et al. 2008) and with the small size of the EUV

pattern observed by TRACE, which also suggests that the flaring region

does not extend high in the corona.

This research was partially supported by Brazil Agencies FAPESP, CNPq and Mackpesquisa, and Argentina Agency CONICET. CGGC also thanks the Observatory of Paris in Meudon, that supported his stay to finish the present work. The authors are in debt to A. Magun and T. Lüthi who provided the calibrated data of the Bern patrol telescopes and of the nulling interferometer at 89.4 GHz. They would also like to thank Dr. Lidia van Driel-Gesztelyi for helpful discussions.

References

- Aschwanden, M. J. 1998, ApJ, 502, 455 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Bai, T., & Ramaty, R. 1979, ApJ, 227, 1072 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Bastian, T. S., Benz, A. O., & Gary, D. E. 1998, ARA&A, 36, 131 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Brown, J. C. 1971, Sol. Phys., 18, 489 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Cristiani, G., Giménez de Castro, C. G., Mandrini, C. H., et al. 2008, A&A, 492, 215 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Dulk, G. A. 1985, ARA&A, 23, 169 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Giménez de Castro, C. G., Raulin, J. P., Makhmutov, V. S., Kaufmann, P., & Costa, J. E. R. 1999, A&AS, 140, 373 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Giménez de Castro, C. G., Costa, J. E. R., Silva, A. V. R., et al. 2006, A&A, 457, 693 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Grigis, P. C., & Benz, A. O. 2008, ApJ, 683, 1180 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Hachenberg, O., & Wallis, G. 1961, Z. Astrophys., 52, 42 [NASA ADS]

- Karlický, M., Fárník, F., & Krucker, S. 2004, A&A, 419, 365 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Kaufmann, P., & Raulin, J.-P. 2006, Phys. Plasmas, 13, 701 [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P., Costa, J. E. R., Correia, E., et al. 2000, in High Energy Solar Physics Workshop - Anticipating Hessi, ed. R. Ramaty, & N. Mandzhavidze, 318, ASP Conf. Ser., 206

- Kaufmann, P., Costa, J. E. R., Giménez de Castro, C. G., et al. 2001, in Proc. of the SBMO/IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and Optoelectronics Conference, 439

- Kaufmann, P., Raulin, J. P., de Castro, C. G. G., et al. 2004, ApJ, 603, L121 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Kiplinger, A. L. 1995, ApJ, 453, 973 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Klein, K.-L., Trottet, G., & Magun, A. 1986, Sol. Phys., 104, 243 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Kliem, B., Dammasch, I. E., Curdt, W., et al. 2002, ApJ, 568, L61 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Krucker, S., Hurford, G. J., MacKinnon, A. L., Shih, A. Y., & Lin, R. P. 2008, ApJ, 678, L63 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Kundu, M. R., White, S. M., Gopalswamy, N., et al. 1994, ApJS, 90, 599 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Lüthi, T., Lüdi, A., & Magun, A. 2004a, A&A, 420, 361 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Lüthi, T., Magun, A., & Miller, M. 2004b, A&A, 415, 1123 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Lee, J. W., Gary, D. E., & Zirin, H. 1994, Sol. Phys., 152, 409 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Lin, R. P., Dennis, B. R., Hurford, G. J., et al. 2002, Sol. Phys., 210, 3 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Melrose, D. B., & Brown, J. C. 1976, MNRAS, 176, 15 [NASA ADS]

- Metcalf, T. R., Hudson, H. S., Kosugi, T., Puetter, R. C., & Pina, R. K. 1996, ApJ, 466, 585 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Pick, M., & Vilmer, N. 2008, A&A Rev., 6

- Qiu, J., Lee, J., & Gary, D. E. 2004, ApJ, 603, 335 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Ramaty, R. 1969, ApJ, 158, 753 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Ramaty, R., & Petrosian, V. 1972, ApJ, 178, 241 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Ramaty, R., Schwartz, R. A., Enome, S., et al. 1994, ApJ, 436, 941 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Saldanha, R., Krucker, S., & Lin, R. P. 2008, ApJ, 673, 1169 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Silva, A. V. R., Wang, H., & Gary, D. E. 2000, ApJ, 545, 1116 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Silva, A. V. R., Share, G. H., Murphy, R. J., et al. 2007, Sol. Phys., 245, 311 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Trottet, G., Vilmer, N., Barat, C., et al. 1998, A&A, 334, 1099 [NASA ADS]

- Trottet, G., Rolli, E., Magun, A., et al. 2000, A&A, 356, 1067 [NASA ADS]

- Trottet, G., Raulin, J. P., Kaufmann, P., et al. 2002, A&A, 381, 694 [EDP Sciences] [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Trottet, G., Krucker, S., Lüthi, T., et al. 2008, ApJ, 678, 509 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- Trubnikov, B. A. 1965, Rev. Plasma Phys., 1, 105 [NASA ADS]

- Vilmer, N. 1987, Sol. Phys., 111, 207 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

- White, S. M., & Kundu, M. R. 1992, Sol. Phys., 141, 347 [CrossRef] [NASA ADS]

Footnotes

Copyright ESO 2009All Tables

Table

1: Derived characteristic of radio radiating electrons for

different magnetic field strengths and view angle equal to 84![]() .

.

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.