| Issue |

A&A

Volume 520, September-October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A93 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014795 | |

| Published online | 08 October 2010 | |

An investigation into the radial velocity variations of

CoRoT-7![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

A. P. Hatzes1 - R. Dvorak2 - G. Wuchterl1 - P. Guterman3 - M. Hartmann1 - M. Fridlund4 - D. Gandolfi1,4 - E. Guenther1 - M. Pätzold5

1 - Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Sternwarte 5, 07778 Tautenburg, Germany

2 -

Institute for Astronomy, University of Vienna, Türkenschanzstrasse 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria

3 -

Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille, UMR 6110, Technopole de

Marseille-Étoile, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France

4 -

Research and Scientific Support Department, European Space Agency, ESTEC, 2200 Noordwijk, The Netherlands

5 -

Rheinisches Institut für Umweltforschung, Universität zu Köln, Abt. Planetenforschung, Aachener Str. 209, 50931 Köln, Germany

Received 15 April 2010 / Accepted 22 June 2010

Abstract

Context. CoRoT-7b, the first transiting ``superearth'' exoplanet, has a radius of 1.7

![]() and a mass of 4.8

and a mass of 4.8

![]() .

The HARPS radial velocity (RV) measurements used for deriving this mass

also detected an additional companion with a period of 3.7 days

and a mass of 8.4

.

The HARPS radial velocity (RV) measurements used for deriving this mass

also detected an additional companion with a period of 3.7 days

and a mass of 8.4

![]() .

The mass of CoRoT-7b is a crucial parameter for planet structure

models, but is difficult to determine because CoRoT-7 is a modestly

active star and there is at least one additional companion.

.

The mass of CoRoT-7b is a crucial parameter for planet structure

models, but is difficult to determine because CoRoT-7 is a modestly

active star and there is at least one additional companion.

Aims. The aims of this paper are to assess the statistical

significance of the RV variations of CoRoT-7b and CoRoT-7c, to

obtain a better measurement of the planet mass for CoRoT-7b, and to

search for additional companions in the RV data.

Methods. A Fourier analysis is performed on the HARPS spectral

data of CoRoT-7. These data include RV measurements, spectral line

bisectors, the full width at half maximum of the cross-correlation

function, and Ca II emission. The latter 3 quantities vary

due to stellar activity and were used to assess the nature of the

observed RV variations. An analysis of a sub-set of the

RV measurements where multiple observations were made per night

was also used to estimate the RV amplitude from CoRoT-7b that was

less sensitive to activity variations.

Results. Our analysis indicates that the 0.85-d and 3.7-d

RV signals of CoRoT-7b and CoRoT-7c are present in the spectral

data with a high degree of statistical significance. We also find

evidence for another significant RV signal at 9 days. An analysis

of the activity indicator data reveals that this 9-d signal most likely

does not arise from activity, but possibly from an additional

companion. If due to a planetary companion the mass is

![]() ,

assuming co-planarity with CoRoT-7b. A dynamical study of the three

planet system shows that it is stable over several hundred millions of

years. Our analysis yields a RV amplitude of

,

assuming co-planarity with CoRoT-7b. A dynamical study of the three

planet system shows that it is stable over several hundred millions of

years. Our analysis yields a RV amplitude of

![]() m s-1 for CoRoT-7b which corresponds to a planet mass of

m s-1 for CoRoT-7b which corresponds to a planet mass of

![]() .

This increased mass would make the planet CoRoT-7b more Earth-like in its internal structure.

.

This increased mass would make the planet CoRoT-7b more Earth-like in its internal structure.

Conclusions. CoRoT-7 is confirmed to be a planet system with at least 2 and possibly 3 exoplanets having masses in the range 7-20

![]() .

If the third companion can be confirmed then CoRoT-7 may represent a case of an ultra-compact planetary system.

.

If the third companion can be confirmed then CoRoT-7 may represent a case of an ultra-compact planetary system.

Key words: star: individual: CoRoT-7 - techniques: radial velocities - planetary systems - stars: activity - starspots

1 Introduction

The 27-cm space telescope CoRoT is devoted to obtaining ultra-high

precision light

curves over a wide field for the dual purpose of asteroseismology and the

detection of transiting exoplanets (Baglin 2006; Auvergne et al. 2009).

This mission resulted in the milestone discovery of

CoRoT-7b, the first transiting superearth whose radius and mass

have been accurately characterized. Photometric measurements of CoRoT-7

made with the

CoRoT Space Telescope from October 2007 to March 2008 revealed a transit like event

with a period of 0.85 days and a depth of a mere 0.03%. A detailed analysis

of the CoRoT light curve and ancillary measurements provided by ground

based observations excluded all sources of false positives and established

with high probability that the transit event was due to a planet with a

radius of 1.7

![]() (Leger et al. 2009).

(Leger et al. 2009).

CoRoT-7 is a G9 main sequence star with an estimated age of

1.2-2.3 Gyr.

From the analysis of the three best spectra obtained with HARPS, and using

several methods, Bruntt et al. (2010) find

![]() K,

K,

![]() ,

[M/H

,

[M/H

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() km s-1.

They also find slightly different values for the mass and radius of CoRoT-7:

km s-1.

They also find slightly different values for the mass and radius of CoRoT-7:

![]() and

and

![]() .

The revised stellar radius results in a

slightly smaller radius for the

planet of

.

The revised stellar radius results in a

slightly smaller radius for the

planet of

![]() .

.

Queloz et al. (2009; hereafter Q09) presented over 100 precise stellar radial velocity (RV) measurements of CoRoT-7 taken between November 2008 and February 2009 with the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrograph mounted on ESO's 3.6 m telescope at La Silla. The RV analysis presented in Q09 was complicated by the relatively high activity of the host star. The CoRoT-7 light curve shows photometric variations of up to 2% with a rotation period of 23 days. The implied spot filling factor suggests an RV ``jitter'' due to stellar activity of more than 10 m s-1(Saar & Donahue 1997) which was confirmed by the RV measurements.

Two approaches were used in Q09 for the analysis

of the RV data.

Fourier pre-whitening resulted in an RV amplitude of

![]() m s-1for CoRoT-7b, while filtering using rotational

harmonics resulted in an amplitude of 1.90

m s-1for CoRoT-7b, while filtering using rotational

harmonics resulted in an amplitude of 1.90 ![]() 0.4 m s-1. By applying correction

terms to these amplitudes due to the effects of the filtering process

a consistent amplitude of 3.5

0.4 m s-1. By applying correction

terms to these amplitudes due to the effects of the filtering process

a consistent amplitude of 3.5 ![]() 0.6 m s-1 was obtained.

This corresponded to a planet mass of

4.8

0.6 m s-1 was obtained.

This corresponded to a planet mass of

4.8 ![]() 0.8

0.8

![]() .

Their analysis

also revealed the presence of a 3.7-d period with an amplitude

of 4.0

.

Their analysis

also revealed the presence of a 3.7-d period with an amplitude

of 4.0 ![]() 0.5 m s-1 that was not associated with

the stellar activity. This signal is most likely due to a second companion with a mass

of 8.4

0.5 m s-1 that was not associated with

the stellar activity. This signal is most likely due to a second companion with a mass

of 8.4 ![]() 0.9

0.9

![]() .

.

One of the most important parameters we can determine for an exoplanet is its mass.

For transiting exoplanets we also know the radius and the

average density of the planet and this is a unique parameter that will allow

us to estimate the planet's composition, e.g. the fraction of metals and/or

water. For transiting exoplanets we also know the radius and average density of

the planet,

![]() .

A high value of

.

A high value of

![]() ,

as seem to be the case for CoRoT-7b (Q09, this

work), indicates a high metal content and a low water abundance.

Interestingly, another low-mass planet with a similar radius

(2.7

,

as seem to be the case for CoRoT-7b (Q09, this

work), indicates a high metal content and a low water abundance.

Interestingly, another low-mass planet with a similar radius

(2.7

![]() )

has recently been found by the MEarth project (Charbonneau et al. 2009), but with a

much lower

)

has recently been found by the MEarth project (Charbonneau et al. 2009), but with a

much lower

![]() than CoRoT-7b. Valencia et al. (2010) using the

mass of CoRoT-7b from Q09

concluded that the internal structure was consistent with

a significantly depleted iron core. However, a mere increase of only

1-

than CoRoT-7b. Valencia et al. (2010) using the

mass of CoRoT-7b from Q09

concluded that the internal structure was consistent with

a significantly depleted iron core. However, a mere increase of only

1-![]() in the mass and a

slightly smaller radius would make the planet more Earth-like.

Clearly, a careful determination of the mass, to go with the radius

provided by the exquisite CoRoT photometric data is absolutely imperative.

This mass must rely on how accurately we can determine the RV amplitude of CoRoT-7b

and unfortunately the activity signal makes this difficult. The details in which

the activity signal is removed may affect the final RV amplitude of CoRoT-7b.

in the mass and a

slightly smaller radius would make the planet more Earth-like.

Clearly, a careful determination of the mass, to go with the radius

provided by the exquisite CoRoT photometric data is absolutely imperative.

This mass must rely on how accurately we can determine the RV amplitude of CoRoT-7b

and unfortunately the activity signal makes this difficult. The details in which

the activity signal is removed may affect the final RV amplitude of CoRoT-7b.

|

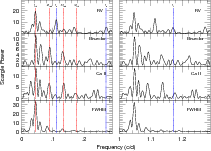

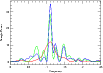

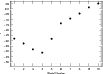

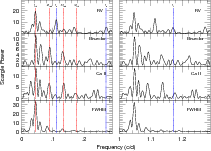

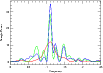

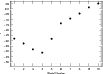

Figure 1: Scargle periodograms of the RV ( top), bisector ( upper middle), Ca II S-index ( lower middle), and FWHM ( bottom) measurements for the frequency range 0-0.3 c d-1 ( left panels) and 1.0-1.3 c d-1 ( right panels). The vertical blue lines mark frequencies seen only in the RV (the one in the right panel is the transit frequency). Vertical red lines mark the rotational frequency and its first 3 harmonics. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

- to assess the statistical significance of CoRoT-7b seen in the RV data;

- to look for possible additional planet signals in the HARPS data;

- to understand the nature of all detected signals in the HARPS RV data;

- to obtain the best possible determination of the mass, and thus density of CoRoT-7b.

2 Observations

The HARPS spectrograph obtained 106 RV measurements for CoRoT-7 over a time span of 4 months. We refer the reader to Q09 for a detailed description of the RV measurements. Besides RV information, the HARPS data also provided information on the activity of the star via the bisector span of the cross correlation function (CCF), the Ca II S-index, and the full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of the CCF. In particular, the line bisector has become a common tool for confirming exoplanet discoveries (e.g. Hatzes et al. 1988; Queloz et al. 2001). Figure 1 of Q09 shows the RV measurements for CoRoT-7 as well as the activity indicators.

3 Scargle periodograms of measured quantities

A periodogram analysis can give us a quick overview as to possible periods

that may be present in the data.

Scargle periodograms were calculated for the four quantities measured

from the HARPS spectra: RV, bisector span,

Ca II S-index, and the FWHM of the CCF.

These are shown in Fig. 1. The RV measurements

contain information about possible planetary companions and activity

while the other quantities should only contain information

on stellar activity. A comparison of the periodograms gives a first indication

as to which peaks in the RV periodogram arise from

activity and those which may be due to companions.

Two frequency ranges are shown. The left panels are for

![]() c d-1 and the right panels are for

c d-1 and the right panels are for

![]() c d-1. The vertical blue lines indicate RV

frequencies not seen in the activity indicators. The one in the right panel

is the CoRoT-7b transit frequency. Because of 1-day aliases all frequencies

in the left panel also appear as peaks at

c d-1. The vertical blue lines indicate RV

frequencies not seen in the activity indicators. The one in the right panel

is the CoRoT-7b transit frequency. Because of 1-day aliases all frequencies

in the left panel also appear as peaks at ![]() in the right panel.

(Note: we have not marked the 1-day alias of the CoRoT transit frequency

at 0.17 c d-1, although one can see a peak at this frequency location.)

The vertical red lines mark the

rotational frequency,

in the right panel.

(Note: we have not marked the 1-day alias of the CoRoT transit frequency

at 0.17 c d-1, although one can see a peak at this frequency location.)

The vertical red lines mark the

rotational frequency,

![]() ,

and its first 3 harmonics (2

,

and its first 3 harmonics (2

![]() ,

3

,

3

![]() ,

and 4

,

and 4

![]() ).

).

There are several important features to note in these periodograms. First,

the dominant peak in all 3 quantities occurs at

![]() c d-1,

the rotational frequency as determined from the CoRoT light curve.

Clearly, RV variations are dominated by the activity

RV jitter from rotational modulation which will complicate the extraction

of RV variations due to bona fide companions.

Second, the periodograms of the bisectors and

Ca II look remarkably similar with the same peaks identifiable in both periodograms.

Third, although the FWHM periodogram shows similar peaks near the

rotational frequency, its shape looks more like the RV periodogram

but without the peaks shown by the vertical dashed lines. The

strong peaks at

c d-1,

the rotational frequency as determined from the CoRoT light curve.

Clearly, RV variations are dominated by the activity

RV jitter from rotational modulation which will complicate the extraction

of RV variations due to bona fide companions.

Second, the periodograms of the bisectors and

Ca II look remarkably similar with the same peaks identifiable in both periodograms.

Third, although the FWHM periodogram shows similar peaks near the

rotational frequency, its shape looks more like the RV periodogram

but without the peaks shown by the vertical dashed lines. The

strong peaks at

![]() and 0.13 c d-1, which are the first

and second harmonics of

and 0.13 c d-1, which are the first

and second harmonics of

![]() ,

are not as strong in the FWHM as in the

bisector and Ca II periodogram.

The most important point is that the

3 peaks seen in the RV data at

,

are not as strong in the FWHM as in the

bisector and Ca II periodogram.

The most important point is that the

3 peaks seen in the RV data at

![]() ,

0.27, and 1.17 c d-1 (and their 1-day aliases) are not found in any of the other

quantities. This is our first hint for the presence of RV variability not

associated with

stellar activity.

,

0.27, and 1.17 c d-1 (and their 1-day aliases) are not found in any of the other

quantities. This is our first hint for the presence of RV variability not

associated with

stellar activity.

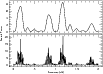

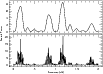

Figure 2 shows the spectral window for the data. As expected it is rather complex with strong sidelobes at +0.013 and 0.04 c d-1. Note that the same spectral window applies for all data (RV, bisectors, Ca II, and FWHM).

4 Frequency analysis of the data sets

It is evident from the periodograms that all spectral quantities have multi-periodic variations. As such they are well suited to the classic technique of pre-whitening often employed in the study of stellar oscillations. In this process a Fourier transform (FT) finds the highest peak in the power spectrum. A least squares fit to the frequency, amplitude, and phase to the found signal is made and then subtracted from the time series. Note that by subtracting this signal we also remove all aliases of the dominant frequency. A subsequent FT on the residuals yields the next dominant frequency in the time series. This sequential subtraction of dominant components is continued until the level of the noise is obtained using the criterion that peaks more than 4 times the Fourier noise level are regarded as real (Kuschnig et al. 1997). This frequency analysis was performed on the HARPS data using the program Period04 (Lenz & Breger 2004).

4.1 Radial velocity data

A pre-whitening analysis of the RV measurements was already presented in Q09. In that analysis a 12-component sine fit was made to the data which resulted in an rms to the fit of 1.81 m s-1. Table 1 lists frequencies using a more conservative solution. In this case the stopping criterion for the pre-whitening (last significant peak) was assessed using a bootstrap randomization procedure (e.g. Kürster et al. 1997). Frequencies above the horizontal line have a false alarm probability less than or equal to about 1%. The rms scatter of the fit to the RV is 2.96 m s-1 which is significantly higher than the mean RV error of 1.89 m s-1. Including the two frequencies below the space break results in an rms scatter of 2.18 m s-1, only slightly worse than the 12-component fit from Q09. Figure 5 in Q09 shows the fit to the RV data provided by the 12-component fit. The 9-component fit listed in Table 1 is of comparable quality so is not shown here.

Most of the frequencies from the FT analysis arise from stellar activity

with the most dominant one being the rotational frequency,

![]() c d-1 and its harmonics. This is noted in the comment column.

The rotational period derived from the RV data is 22.32

c d-1 and its harmonics. This is noted in the comment column.

The rotational period derived from the RV data is 22.32 ![]() 0.08 days,

hence larger than the value of 21.65

0.08 days,

hence larger than the value of 21.65 ![]() 0.03 days obtained from the CoRoT

light curve.

It is not known whether this

difference merely reflects the difficulty in measuring the rotational period

from such complex RV and light curves, or if this is a real difference

due to possibly differential rotation.

There are 3 frequencies denoted f1, f2, and f3 that are not readily

associated with stellar activity. The frequency f1 is the CoRoT-7b transit

frequency of 1.17165 c d-1, f2 is the 3.7-day planet reported

by Q09, and f3 corresponds to a period of 9.02 days and will discussed at

length below.

In Table 1 there are three additional frequencies above the space break and

two below that could not be readily associated

with rotational harmonics, but as we show below these are most likely

related to the activity signal. For convenience in referencing we denote

sequentially the additional frequencies f4 - f8, although

for the following discussion f1, f2, and f3 are the most important.

0.03 days obtained from the CoRoT

light curve.

It is not known whether this

difference merely reflects the difficulty in measuring the rotational period

from such complex RV and light curves, or if this is a real difference

due to possibly differential rotation.

There are 3 frequencies denoted f1, f2, and f3 that are not readily

associated with stellar activity. The frequency f1 is the CoRoT-7b transit

frequency of 1.17165 c d-1, f2 is the 3.7-day planet reported

by Q09, and f3 corresponds to a period of 9.02 days and will discussed at

length below.

In Table 1 there are three additional frequencies above the space break and

two below that could not be readily associated

with rotational harmonics, but as we show below these are most likely

related to the activity signal. For convenience in referencing we denote

sequentially the additional frequencies f4 - f8, although

for the following discussion f1, f2, and f3 are the most important.

|

Figure 2: Spectral window function for the HARPS measurements. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1: Frequencies and amplitudes found by a pre-whitening procedure on the HARPS RV data.

The CoRoT light curve for CoRoT-7 is complex and shows evidence for spot evolution on time scales of less than 150 days, or comparable to the time span of our RV measurements. Although the fit to the data using the full RV data set is excellent, the Fourier sine components may not accurately represent the activity variations over such a long time span. An analysis of the data in subsets of shorter time interval may minimize the uncertainties in the activity signal due to spot evolution.

To minimize possible effects of spot evolution, a frequency analysis was also performed on sub-sections of the HARPS data. The RV data were divided into 3 sets each roughly spanning one rotation period. The time span of these data sets are listed in the first 3 lines of Table 2. When analyzing data containing periods comparable to the time span of the data string there can be risks to using the pre-whitening procedure. This is certainly true for the rotational period and to some extent to the 9-d period since it only undergoes 2 cycles over the time span of the subset observations. Likewise the 0.85-d suffers from being severely under-sampled for some of the data subsets. In short, alias effects and spectral leakage may result in a spurious period being identified and removed from the data and thus resulting in an erroneous solution.

Indeed, when performing a straight pre-whitening procedure to Subset 1 the dominant

frequency is f = 0.13 c d-1 and the rotational frequency appears

at 0.05 c d-1. Only f2 is recovered. However, when one first

fits the data using the CoRoT-7b frequency first, the procedure recovers

both f2 and f3. A pre-whitening analysis on Subset 2 recovers

![]() ,

f1, and f2, but the nearest frequency to f3 was at 0.08 c d-1.

Subset 3 also yields different results. The dominant frequency occurs at 0.03 c d-1,

significantly different from

,

f1, and f2, but the nearest frequency to f3 was at 0.08 c d-1.

Subset 3 also yields different results. The dominant frequency occurs at 0.03 c d-1,

significantly different from

![]() .

Both f2 and f3 are recovered, but the nearest frequency

to f1, the transit frequency, is at 1.18 c d-1.

.

Both f2 and f3 are recovered, but the nearest frequency

to f1, the transit frequency, is at 1.18 c d-1.

Therefore, in fitting the subset

data we assumed that f1, f2, and f3 were present in the data

asked the question ``Can the subset

data be fit using these frequencies?'' To answer this we first

fit and removed the frequencies that were found in the full data set,

namely

![]() ,

f1, f2, and f3. In this fitting only the frequencies were

held fixed, but the amplitudes and phases were allowed to vary. The pre-whitening

procedure was continued until the rms fit to the data was comparable to the HARPS

measurement error (better than 2 m s-1).

,

f1, f2, and f3. In this fitting only the frequencies were

held fixed, but the amplitudes and phases were allowed to vary. The pre-whitening

procedure was continued until the rms fit to the data was comparable to the HARPS

measurement error (better than 2 m s-1).

Tables 3-5 lists the frequencies and amplitudes

from the Fourier analysis. In all cases the rms fit of the data is comparable

to the mean error of the HARPS measurements.

The amplitude of the

![]() ,

0.27, and 1.17 c d-1 signals remain relatively constant.

The largest amplitude variations are found for the frequency associated

with rotation, but it is not clear how significant these are given the

data sub-interval spans only one rotation period. The amplitude is thus

probably not well determined. In summary, this has established

that the RV variations in the subset data are consistent with the

presence of f1, f2, and f3, and with amplitudes comparable to those

found in the full data set. Note that the additional frequencies found in the

pre-whitening procedure can be identified with frequencies found in the full

data set analysis.

,

0.27, and 1.17 c d-1 signals remain relatively constant.

The largest amplitude variations are found for the frequency associated

with rotation, but it is not clear how significant these are given the

data sub-interval spans only one rotation period. The amplitude is thus

probably not well determined. In summary, this has established

that the RV variations in the subset data are consistent with the

presence of f1, f2, and f3, and with amplitudes comparable to those

found in the full data set. Note that the additional frequencies found in the

pre-whitening procedure can be identified with frequencies found in the full

data set analysis.

The referee suggested an analysis of the longest data string between

JD

= 2 454 847.6-2 454 884.7 as this has few gaps (Subset 4). A Fourier pre-whitening

procedure found f1 and f2, but was unable to find f3. This was also

the case when

we generated a fake data set using the periods listed in Table 1, sampled

in the same manner as Subset 4, and with random noise with

![]() m s-1. The pre-whitening procedure was also unable to detect f3even though it was present in the data. Table 6 lists the results of

the Fourier analysis by first fitting

m s-1. The pre-whitening procedure was also unable to detect f3even though it was present in the data. Table 6 lists the results of

the Fourier analysis by first fitting

![]() ,

f1, f2, and f3- similar to the procedure used for generating Tables 3-5. Note that the

amplitude of f3 is considerably lower than was found for Subsets 1-3.

This may be an indication that it is an artifact of the activity signal.

However, when performing the same analysis on the fake data generated

using the frequencies and amplitudes in Table 1 (again with

the appropriate sampling and noise), the fitted amplitude for

f3 is a factor of 3 less. The fitted amplitudes for the fake data

are listed in the third column of Table 6.

So, any evidence for amplitude variations

for f3 is inconclusive.

,

f1, f2, and f3- similar to the procedure used for generating Tables 3-5. Note that the

amplitude of f3 is considerably lower than was found for Subsets 1-3.

This may be an indication that it is an artifact of the activity signal.

However, when performing the same analysis on the fake data generated

using the frequencies and amplitudes in Table 1 (again with

the appropriate sampling and noise), the fitted amplitude for

f3 is a factor of 3 less. The fitted amplitudes for the fake data

are listed in the third column of Table 6.

So, any evidence for amplitude variations

for f3 is inconclusive.

Table 2: The data subsets.

Table 3: Frequencies found in data Subset 1.

Table 4: Frequencies found in data Subset 2.

Table 5: Frequencies found in data Subset 3.

Table 6:

Frequencies found in data Subset 4 using the same

analysis as Tables 3-5, i.e. first removing the contribution of

![]() ,

f1, f2, f3. Column 3 shows the amplitude

derived using fake data (see text).

,

f1, f2, f3. Column 3 shows the amplitude

derived using fake data (see text).

4.2 Frequency analysis of activity indicators

A Fourier analysis with pre-whitening

was performed on the bisector, Ca II S-index, and FWHM

measurements. These are listed in Tables 7-9.

The pre-whitening procedure was continued beyond the last frequency

we considered significant

to see if at any point a frequency was detected that coincided

with either f1, f2, and f3.

Both the bisector and FWHM measurements show frequencies near

f2:

![]() c d-1 (P = 3.6 d), but only after

pre-whitening the data well past our stopping criterion

(7th frequency found in the bisector and the 6th frequency

in the FWHM). These amplitude frequencies are essentially at or below the noise level.

Furthermore, when

we phase the bisector and FWHM data after removing all components except those

near the 3.7-d period, no obvious sinusoidal variations are present. We therefore

do not consider these frequencies to be significant.

c d-1 (P = 3.6 d), but only after

pre-whitening the data well past our stopping criterion

(7th frequency found in the bisector and the 6th frequency

in the FWHM). These amplitude frequencies are essentially at or below the noise level.

Furthermore, when

we phase the bisector and FWHM data after removing all components except those

near the 3.7-d period, no obvious sinusoidal variations are present. We therefore

do not consider these frequencies to be significant.

Table 7: Frequencies found in the bisector data using a pre-whitening procedure.

Table 8: Frequencies found in the Ca II data using a pre-whitening procedure.

Table 9: Frequencies found in the FWHM data using a pre-whitening procedure.

5 Statistical significance of the RV frequencies

A common way of assessing the statistical significance of a period found

in time series data is via the Scargle periodogram (Scargle 1982). In this formulation

of the Fourier transform the power of a peak is related to a statistical

significance rather than the amplitude of the periodic signal. If

a peak in the Scargle periodogram has power, z, then the false alarm

probability (FAP, probability that it is due to noise) can be calculated under

two cases. The first is if one is searching for an unknown signal

over a wide frequency range, and the second is for a period known to be

present in the data. In the former, the FAP is given by

FAP

![]() )

)

![]() ,

where N is the number of independent

frequencies. For the latter, the FAP is given by FAP

,

where N is the number of independent

frequencies. For the latter, the FAP is given by FAP

![]() ,

where now there is only one independent frequency (N=1).

,

where now there is only one independent frequency (N=1).

5.1 Statistical significance of 0.85-d RV period

Because we know that a 1.1716 c d-1 signal is present in the CoRoT light

curves we should ask: what is the FAP for a signal

at the known frequency of the CoRoT transit? Table 10

lists the Scargle power, z, and the false alarm

probability, FAP =

![]() for the peak at 1.17 c d-1 in each of the

data sets. Clearly, the

0.85-d period in the RV data is significant, whereas the false alarm probability of the

corresponding peak at the same frequency in any of the activity indicators

is over a factor of 20 higher.

for the peak at 1.17 c d-1 in each of the

data sets. Clearly, the

0.85-d period in the RV data is significant, whereas the false alarm probability of the

corresponding peak at the same frequency in any of the activity indicators

is over a factor of 20 higher.

Of course, the Scargle prescription uses the rms scatter of the full data set to set the noise level in assessing the FAP. If there is real variablity in the data this increases the rms scatter and results in an over-estimate of the FAP. For weaker signals in time series that are dominated by a stronger one, you should subtract the contribution of the dominant signal to get a better estimate of the FAP for the weaker signal.

Table 10: Scargle power and False Alarm Probability for the Peak at 1.17 c d-1, for RV, bisector, and Ca II data.

|

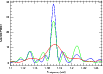

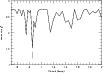

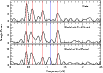

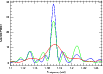

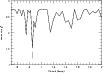

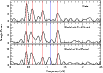

Figure 3: Scargle periodograms resulting from sequential adding of data subsets. Red line: subset 1, green line: subset 1 plus subset 2, blue: all data sets. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 3 shows the Scargle periodogram of the RV residuals after

subtracting all sine components except that due to the

CoRoT planet at 0.85 days.

The red line

shows the Scargle periodogram

using Subset 1, the green is after adding Subset 2, and the blue is

the periodogram of the full data set. The fact that the Scargle power increases

with the addition of each new data set (i.e. increasing statistical

significance) gives us some reassurance that the signal is indeed present

in all data sets. The final Scargle power of the 1.171 c d-1 signal is

z = 39, which results in an FAP of ![]() 10-17 for

a known signal in the data.

The FAP that noise would

create a peak with power higher anywhere in the full spectral

range (first equation from above)

is

10-17 for

a known signal in the data.

The FAP that noise would

create a peak with power higher anywhere in the full spectral

range (first equation from above)

is ![]() 10-15. Thus

this signal would be highly significant even if

we were unaware of the CoRoT transit period.

10-15. Thus

this signal would be highly significant even if

we were unaware of the CoRoT transit period.

5.2 Statistical significance of 3.7-d RV period

The 3.7-d period ( f2 = 0.11 c d-1) has Scargle power of 5.67. Based on this power level we would normally not be considered the signal to be significant. An FAP was assessed by using a bootstrap randomization method. The RV values of the data (with all signals present) were shuffled randomly keeping the observation times fixed and a periodogram calculated for this random data. After 105 such ``shuffles'' the number of random periodograms having power greater than 5.67 over the frequency range 0-0.5 d-1 gave an estimate of the FAP. This value was 0.3.

However, as stated earlier, this FAP may be overestimated due to the

presence of the other signals in the RV data. To get a more realistic

assessment of the false alarm probability the

contributions from all sine components except that due to the

3.7-day period were subtracted from the three subsets

(the 3.7-d residuals).

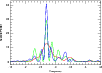

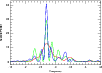

Figure 4 shows the Scargle

periodogram after sequentially adding the residual RVs from each

of the data subsets.

The Scargle power increases with the addition of each subset and the

final value is 40 which corresponds to an FAP ![]() 10-16.

10-16.

5.3 Statistical significance of 9.0-d RV period

The peak at 9 days in the RV periodogram has Scargle power of 12.13.

A bootstrap randomization with 105 shuffles yields an FAP

![]() .

We can be confident that this signal is

statistically significant even without subtraction of the other signals.

Figure 5 shows the Scargle periodograms for the 9-d RV residuals, i.e. the

RV measurements with all signals except the 9-d period subtracted, and

as each subset is added. The increase in the statistical significance

with the addition of more RV measurements is an indication of a

long-lived and coherent signal. The FAP of the final peak after including

all RV measurements is

.

We can be confident that this signal is

statistically significant even without subtraction of the other signals.

Figure 5 shows the Scargle periodograms for the 9-d RV residuals, i.e. the

RV measurements with all signals except the 9-d period subtracted, and

as each subset is added. The increase in the statistical significance

with the addition of more RV measurements is an indication of a

long-lived and coherent signal. The FAP of the final peak after including

all RV measurements is ![]() 10-16.

10-16.

|

Figure 4: Scargle periodograms resulting from sequential adding of residual RV data for the 3.7-day period. Red line: subset 1, green line: subset 1 plus subset 2, blue: all data sets. All sine components except the that associated with the 9.02-day period. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 5: Scargle periodograms resulting from sequential adding of residual RV subsets for the 9-day period. Red line: subset 1, green line: subset 1 plus subset 2, blue: all data sets. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Is the 0.85-d period an alias of a rotation harmonic?

The Scargle periodograms in Fig. 1 are

dominated by the rotational frequency,

![]() .

However, there is also power at the first

two harmonics of the rotational frequency, namely 2

.

However, there is also power at the first

two harmonics of the rotational frequency, namely 2

![]() and

and

![]() .

Indeed, Q09 applied harmonic filtering using

the rotational frequency and its first two harmonics to remove the signature of activity. Because of this there

is some concern that the 1.1715 transit frequency is close to the one-day alias of the 3rd harmonic

of the rotational frequency (i.e.

.

Indeed, Q09 applied harmonic filtering using

the rotational frequency and its first two harmonics to remove the signature of activity. Because of this there

is some concern that the 1.1715 transit frequency is close to the one-day alias of the 3rd harmonic

of the rotational frequency (i.e.

![]() c d-1). In the best case, the activity signal can thus contribute

some power at the orbital frequency of CoRoT-7b.

In the worse case all the RV signal at this frequency could arise from

activity.

c d-1). In the best case, the activity signal can thus contribute

some power at the orbital frequency of CoRoT-7b.

In the worse case all the RV signal at this frequency could arise from

activity.

Q09 argued that because repeated measurements were taken on the same nights, that this alias effect was minimized and that the 0.85-d RV period was the one actually present in the data. To investigate whether alias effects of a rotational harmonic can account for the observed 0.85-d period in the RV data we performed an analysis on a subset of the RV consisting only of those nights for which at least 3 RV measurements were made during the night. In the following analysis it is assumed that the activity signal contributes a constant value to the measured RV on a given night. This is a reasonable assumption. The maximum time separation between the first and last measurement on a given night is less than 4 h. This corresponds to a change in rotation phase of only 0.007. The contribution of stellar activity to the measured RV should thus be a constant over that time. This also assumes that spot evolution over 4 h is negligible. Meanwhile, the change in orbital phase of CoRoT-7b is 0.2 and should cause the dominant variations observed in the RV during the course of the night.

It is not strictly true that the non-CoRoT-7b RV variations are constant during the night. The orbital motion due to the CoRoT-7c should produce an appreciable variation over 4 hours. However, this contribution is also relatively small. Over 4 hour time span the orbital phase of CoRoT-7c only changes by 0.05 which corresponds to a maximum RV variation of only 1.5 m s-1 well below the measurement error.

There were 7 nights where at least 3 RV measurements of CoRoT-7 were made resulting in a total of 21 measurements. The data from these nights were treated as 7 independent data sets with each one have a different a zero-point velocity which could vary from night to night. A least squares sine-fit the 7 data sets was made keeping the period fixed to the transit period of 0.8535 days, but allowing phase and the zero-point value for each night to vary. The advantage of such an approach is that it is a ``minimal impact'', low pass filter that makes no assumptions about the underlying time variability due to stellar activity, only that it is constant on a given night.

The top panel of Fig. 6 shows the

Scargle periodogram of these 21 RV measurements after

subtracting the individual zero-point offsets determined by the least squares fitting. The

strongest peak is at the transit frequency of 1.1715 c d-1 and

with a smaller peak at the

alias frequency of 0.1715 c d-1. Figure 7

shows the RV measurements

phased to the period of CoRoT-7b and the alias period (5.7 days). The ``cleaner'' phase diagram

of the 0.85 d period supports that this is the true period in the data, and not the alias of

![]() .

.

The false alarm probablity of the peak at 1.1715 c d-1 was

assessed using a bootstrap randomization procedure. The RV values were shuffled

![]() times keeping the observed times fixed and periodograms calculated

for this random data. Over the frequency range

times keeping the observed times fixed and periodograms calculated

for this random data. Over the frequency range

![]() c d-1there was only four instances

where the periodogram of the random exceeded the power of the real data.

The FAP for this signal is thus

c d-1there was only four instances

where the periodogram of the random exceeded the power of the real data.

The FAP for this signal is thus ![]()

![]() .

We should note that this

bootstrap was evaluated over the full frequency range 0-2 c d-1.

Since we are interested in the known frequency of CoRoT-7c it is more

appropriate to evaluate the bootstrap

over a much narrower range centered on

.

We should note that this

bootstrap was evaluated over the full frequency range 0-2 c d-1.

Since we are interested in the known frequency of CoRoT-7c it is more

appropriate to evaluate the bootstrap

over a much narrower range centered on

![]() c d-1. The FAP of this signal is almost certainly much less.

c d-1. The FAP of this signal is almost certainly much less.

|

Figure 6: (Top) Scargle periodogram of the data set consisting of 7 nights where at least 3 RV measurements were made. The measurements from each night were considered an independent data set and a fit was made using the period of CoRoT-7b and allowing zero point offset from each night to vary. The periodogram is of the data with the offset to each night subtracted. (Bottom) Same as in the top panel but with the addition of 16 nights for which two RV measurements were made per night. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

There were an additional 16 nights where 2 RV measurements were taken

of CoRoT-7. The time separation of these points are large enough to provide

some good sampling of the 0.85-d sine wave presumed to be in the data.

These nights were added to the data subset of 3 points per night

to give a total of 53 data points spread over 23 nights.

A new fit was performed, again allowing the

nightly zero-point values to vary, but keeping the period fixed to the transit period.

The lower panel of Fig. 6

shows the periodogram of these data with the zero point offsets applied. Note

that the Scargle power has significantly increased indicating a more signficant

detection (FAP ![]() 10-16). Also, the frequency at

1.1716 c d-1 is still higher than the alias frequency. A phase diagram

of these data will be shown below when we present orbital solutions.

10-16). Also, the frequency at

1.1716 c d-1 is still higher than the alias frequency. A phase diagram

of these data will be shown below when we present orbital solutions.

|

Figure 7: (Top) RV measurments of the 7-night data set (zero-point offsets applied) phased to the period of CoRoT-7b. (Bottom) same measurements phased to the alias period of 5.82 days. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

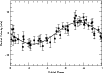

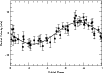

We also investigated whether the period of CoRoT-7b could be extracted from the

data without a priori knowledge of the transit period.

To do this a range of periods

were fit to the 53 RV measurements of the data set with

multiple observations per night. At each trial fit the period was fixed, but the phase and

zero-point offset were allowed to vary. Figure 8 shows the reduced

![]() fit to the data as a function of the fitting period. Good fits

occur at

periods where

fit to the data as a function of the fitting period. Good fits

occur at

periods where ![]() is minimized. This procedure could be considered as a variant

of the phase dispersion minimization technique of Stellingwerf (1978), but

which allows the mean value of

individual data sets to float (i.e. a ``floating mean'' phase dispersion minimization). The

deepest

is minimized. This procedure could be considered as a variant

of the phase dispersion minimization technique of Stellingwerf (1978), but

which allows the mean value of

individual data sets to float (i.e. a ``floating mean'' phase dispersion minimization). The

deepest ![]() minimum is near the period of CoRoT-7b (vertical line).

Other minima are clearly alias periods and phasing of the data to these periods

does not produce as clean a phase diagram as for the CoRoT-7b period.

minimum is near the period of CoRoT-7b (vertical line).

Other minima are clearly alias periods and phasing of the data to these periods

does not produce as clean a phase diagram as for the CoRoT-7b period.

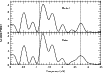

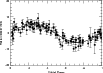

6.1 Fourier analysis of nightly offsets

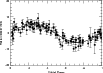

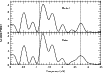

As a sanity check we performed a Fourier analysis on the nightly offsets produced by our least squares fitting. If these derived nightly offsets have some relationship to the activity we should see evidence of the rotational period. The top panel of Fig. 9 shows the Fourier transform of the nighty offsets (23 values). The highest peak corresponds to the rotational frequency of CoRoT-7 (indicated by the vertical dashed line). This indicates that the nightly zero-point offset indeed follows the RV rotational modulation due to activity.

Of interest is when we pre-whiten the nightly offsets to search for additional periods. The second panel shows the offset data after removing the contribution of the rotational frequency. The highest peak corresponds to a frequency of 0.27 c d-1 (indicated by the vertical line). The bottom panel shows the amplitude spectrum of the residuals after removing the contribution of the 0.27 c d-1 frequency. The highest peak corresponds to 0.112 c d-1, close to the 0.11 c d-1 frequency found in the RV (indicated by the vertical line). It is reassuring that the nightly offsets show evidence for the rotation period of the star, but also the 3.7-d and 9-d period found in the RV analysis.

|

Figure 8:

The reduced |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 9: A pre-whitening on the zero-point offsets of the multi-measurement nights found by the least squares fitting. ( Top) Amplitude spectrum of the zero-point values. The dashed line indicates the rotation period of CoRoT-7b. ( Middle) The amplitude spectrum after removing the rotational frequency. The vertical line corresponds the frequency of the 3.7-d period of CoRoT-7c. ( Bottom) The amplitude spectrum after also removing 3.7-d period signal. The vertical line corresponds to the frequency f3. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

7 On the nature of the 9-d period

|

Figure 10:

(Top) Scargle periodogram for the fit to RV first data subset (truncated JD = 4775-4807)

sampled in the same manner as the data and with noise at a level of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Q09 the two approaches to the RV data analysis (harmonic filtering and

Fourier

pre-whitening) agree on the presence of a 0.85-d and 3.7-d period in the data.

The main difference to the two approaches was that the pre-whitening procedure

yielded a significant period at 9-d, whereas this signal was absent in the harmonic filtering of activity

signal. The obvious interpretation is that the 9-d period arises from the activity signal.

However, the harmonic filtering worked on sub-sets of the data that were roughly

the length of the rotation period, whereas the pre-whitening

procedure was performed on the full dataset.

The 9-d period is very close to

![]() ,

i.e.

the first harmonic of the rotation period. There is a danger that when applying

harmonic filtering one may remove real signals not associated with a rotational harmonic.

,

i.e.

the first harmonic of the rotation period. There is a danger that when applying

harmonic filtering one may remove real signals not associated with a rotational harmonic.

To test this hypothesis the frequency solution of the Subset 1 (Table 3)

was used

to generate a fake data set. This fake data included the signals f1, f2,

and f3.

The fits were sampled in exactly the same way as the real data and

noise at a level of

![]() m s-1 was also added. The Scargle periodogram of the

fake data (top panel) is compared to the periodograms of the real data

(lower panel) in Fig. 10. The frequency of the input

3.7-d and 9-d period signals are shown as vertical lines.

m s-1 was also added. The Scargle periodogram of the

fake data (top panel) is compared to the periodograms of the real data

(lower panel) in Fig. 10. The frequency of the input

3.7-d and 9-d period signals are shown as vertical lines.

There are two things to note about this figure. The periodogram of the fake data looks exactly like the real data, as it should. After all, the rms scatter about the fit is under 2 m s-1. If you fit the data you fit the periodogram. Note, however, because of the short data window the true frequency in the data, f3, appears at a slightly different frequency of 0.12 c d-1.

This fake Subset 1 data set was analyzed using harmonic analysis

and pre-whitening. The data was first fit using the rotational frequency

and its first two harmonics (

![]() ,

2

,

2

![]() ,

and 3

,

and 3

![]() )

as well

as 0.5

)

as well

as 0.5

![]() (there was evidence for the presence of this frequency,

see Table 1). The frequencies were kept fixed, but the amplitude and phase

were made to vary. The pre-whitening procedure was then carried out to

find additional frequencies. The results are listed in Table 11. The

pre-whitening procedure found only 2 additional frequencies, f1 and

f2, but not f3 even though it was present in this fake data.

The same result was found when applying this procedure to the other

data sets.

(there was evidence for the presence of this frequency,

see Table 1). The frequencies were kept fixed, but the amplitude and phase

were made to vary. The pre-whitening procedure was then carried out to

find additional frequencies. The results are listed in Table 11. The

pre-whitening procedure found only 2 additional frequencies, f1 and

f2, but not f3 even though it was present in this fake data.

The same result was found when applying this procedure to the other

data sets.

Harmonic filtering was also performed on the full RV (real) data set

by first fitting

![]() ,

2

,

2

![]() ,

and 3

,

and 3

![]() to the data and

then continuing the pre-whitening procedure to find additional frequencies.

After all frequencies were found the solution optimized by fitting all

components simultaneously.

The results are shown in

Table 12. The frequencies f1,

f2, and f3 were recovered in spite of the harmonic pre-filtering.

to the data and

then continuing the pre-whitening procedure to find additional frequencies.

After all frequencies were found the solution optimized by fitting all

components simultaneously.

The results are shown in

Table 12. The frequencies f1,

f2, and f3 were recovered in spite of the harmonic pre-filtering.

This investigation has demonstrated that one should be careful in filtering the time

series data using harmonics of the

rotational frequency of CoRoT-7 on a limited time span data set. In this case,

using rotational harmonics essentially filtered out the

real period that was in the simulated data.

When applying rotational harmonic

filtering to the full real data set the 9-d period was still recovered.

The reason for this is that over a 23-d time span there is

little difference between

![]() c d-1 and the first harmonic

of the rotational frequency,

c d-1 and the first harmonic

of the rotational frequency,

![]() c d-1. Harmonic filtering will essentially remove this signal. However,

over the 100 days that the RV data were acquired the subtle frequency difference

between f3 and 2

c d-1. Harmonic filtering will essentially remove this signal. However,

over the 100 days that the RV data were acquired the subtle frequency difference

between f3 and 2

![]() can be resolved and harmonic filtering cannot

fully remove the signal due to f3. When performing an analysis on data subsets

it is instructive to

look also at the full data covering the longest time span.

can be resolved and harmonic filtering cannot

fully remove the signal due to f3. When performing an analysis on data subsets

it is instructive to

look also at the full data covering the longest time span.

7.1 Bisector - RV correlations

Table 11: Frequencies found in the simulated data set of Subset 1 (Fig. 10) using a pre-whitening procedure and harmonic analysis.

Table 12: Pre-whitened frequencies found in the RV data after first fitting the rotational frequency and its first 2 harmonics.

The HARPS data also contain three indicators of activity: the FWHM of the CCF, the bisector of the CCF, and the Ca II emission measure. Of these 3 activity indicators only the line bisectors have a direct relationship to the RV variations due to activity. Ca II emission originates in plage and these regions do not necessarily have the same surface distribution as spots. For cool spots the FWHM is out-of-phase with the RV variations. The FWHM is a minimum when the spot distortions are the wings of the spectral line (i.e. limb of star) and a maximum when the spots are at disk center (zero RV). Thus there is a phase shift ofRV variations caused by cool spots should show an anti-correlation (negative slope) with the bisector variations (see Queloz et al. 2001). The RV variations of CoRoT-7 do show a slight anti-correlation with the bisectors (left panel of Fig. 11). If an RV signal is not due to activity, then removing this from the observed RV measurements should result in a stronger correlation between the bisectors and RV variations. Indeed, when one removes that signal of the 0.85-d, 3.7-d, and 9-d period from the RV data the bisector span - RV variations become more correlated (r = -0.42, right panel). This suggests that the 0.85-d, 3.7-d, and 9-d periods (i.e. f1, f2, and f3) found in the RV data are not associated with activity.

| Figure 11: (Left) Bisctor span of the CCF versus the RV measurements. The correlation coefficient is -0.28. (Right) The Bisector-RV correlation after f1, f2, f3 (planet signals) have been removed from the data. The correlation coefficient is -0.42. |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 12 shows the correlation coefficient between the bisector and RV measurements as a function of data sets with the contributions of various frequencies removed (denoted ``Model Number'') Model 1 is to the original RV data set. Model 2 is this data set with the 0.85-d period removed. Model 3 is the previous model, but with the 3.7 d period also removed. Model 4 is the data set with the 0.85-d, 3.7-d, and 9-d periods removed. Note that the correlation coefficient becomes more negative with the removal of each data set suggesting that these 3 periods are not associated with stellar activity.

Model 5 represents Model 4 -

![]() .

Each subsequent model is the previous

model with

successive frequencies listed in Table 1 removed (and skipping of course

f1, f2, and f3 already subtracted in Model 4). The fact that the

RV-Bisector variations become more uncorrelated with

the removal of additional frequencies

suggests that all frequencies in Table 1 except f1, f2, and

f3 are most likely due

to activity.

.

Each subsequent model is the previous

model with

successive frequencies listed in Table 1 removed (and skipping of course

f1, f2, and f3 already subtracted in Model 4). The fact that the

RV-Bisector variations become more uncorrelated with

the removal of additional frequencies

suggests that all frequencies in Table 1 except f1, f2, and

f3 are most likely due

to activity.

|

Figure 12:

The correlation coefficient of the CCF bisector span with RV

as a function of different versions of the RV data with the

frequencies in Table 1 removed. Model 1: raw

data, Model 2: f1 removed, Model 3: f1 and f2 removed,

Model 4: f1, f2, and f3 removed. Model 5: Model 4 and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Because the RV variations are directly related to the bisector

variability we can use the temporal variations of the RV to produce

a predicted bisector variability. Saar & Donahue (1997) gave relationships

relating both the bisector span and RV amplitude as a function of spot filling

factor and rotational velocity of the star. The RV-to-Bisector amplitudes

ratio from their expressions is predicted to be about a factor of 10. However,

the exact ratio depends on several factors, primarily how one measures

the bisector span and which spectral lines are used. Their result cannot

be directly compared to the bisector measurements of the CCF from the HARPS

data.

A better way is to use the RV-to-Bisector amplitude

ratio estimated by comparing the amplitudes of

frequencies found in both the RV and bisector amplitude spectra and using data

where these quantities (bisector and RV) were measured in a consistent way.

The RV frequencies

![]() c d-1 and

0.094 c d-1 in Table 1 have amplitudes of 7.5 m s-1 and

5.69 m s-1. The corresponding frequencies in the bisector amplitude

spectrum

have amplitudes of 4.21 m s-1 and 2.81 m s-1, respectively.

This implies that the RV-to-Bisector amplitude is

c d-1 and

0.094 c d-1 in Table 1 have amplitudes of 7.5 m s-1 and

5.69 m s-1. The corresponding frequencies in the bisector amplitude

spectrum

have amplitudes of 4.21 m s-1 and 2.81 m s-1, respectively.

This implies that the RV-to-Bisector amplitude is ![]() 2.

2.

We created a model of the bisector variations based on the amplitude spectrum of the RV measurements. Two fake data sets of bisector variations were generated. The first used all the frequencies in Table 1, excluding f1, f2, and f3. All amplitudes in Table 1 were reduced by a factor 0.5 corresponding to the bisector-to-RV amplitude ratio. The sampling of this time series was the same as the actual data. The bisector variations have an rms scatter of 4.5 m s-1 after removal of the dominant frequencies. This was taken as the mean bisector error and random noise at this level was added to the fake bisector data. The second data set was similar to the first one, but the frequency f3 was present with the appropriately scaled amplitude (i.e. only f1 and f2 were removed).

The top panel of Fig. 13 shows the Scargle periodogram of the actual bisector measurements. The middle panel shows the periodogram of the fake data, but without the presence of the 9-d period. The bottom panel shows the periodogram of the fake bisector data with the 9-d period present. Vertical red lines show the rotation frequency and its first 3 harmonics. The vertical blue line shows the frequency corresponding to the 9-d period.

There are two interesting features about this figure.

First, the periodogram of the

fake bisector data without the 9-d period looks qualitatively like the real data.

Many of the same peaks are seen in both periodograms.

The ratio of the amplitudes are not quite correct probably due to

the bisector data having more complicated noise characteristics than the

Gaussian noise in our simple model. Furthermore, for

high frequency components that the RV-to-Bisector amplitude ratio may be

different. The second important feature to note is that in the periodogram of the

fake data with the 9-d period present

there is a signficant peak at

![]() c d-1

that is not seen in the data periodogram. If the 9-d period was

due to activity we should have seen a

corresponding peak in the periodogram of the bisectors and most likely

in the Ca II and FWHM.

This also argues in favor

of the 9-d period not being related to activity.

c d-1

that is not seen in the data periodogram. If the 9-d period was

due to activity we should have seen a

corresponding peak in the periodogram of the bisectors and most likely

in the Ca II and FWHM.

This also argues in favor

of the 9-d period not being related to activity.

|

Figure 13: (Top) Scargle periodogram of the CCF bisector variations. (Middle) Scargle periodogram of a fit generated using the RV frequencies of Table 1, but without f1, f2, and f3present. Amplitudes were adjusted according to the measured RV-to-Bisector amplitudes. Random noise at the level observed for the bisector measurements were also added. (Bottom) Same as for the middle panel but with f3 (9-d period) present. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

8 A search for transits from CoRoT-7d

The CoRoT-7 light curve was analyzed to see if a 9-d transit signal could be found in the data. A similar investigation was already performed to search for transits from CoRoT-7c, but none was found (Q09). If the orbits of all planets are co-planar we do not expect to see transits from CoRoT-7d. However, if substantial differences of the orbital inclination between the planets exist, CoRoT-7d may well transit in spite of having a larger orbital radius than CoRoT-7c.

The CoRoT-7 light curve first had to be filtered for the large variations due to the stellar activity. This was done by: 1) normalizing the light curve by the maximum value; 2) performing outlier rejection; 3) reducing residual orbital effects by using a running median of length one orbit; and 4) tracking slow variations using a sliding polynomial of 12 hours and subtracting these. Finally, we fit the transit curve of CoRoT-7b and subtracted that from the light curve.

This processed light curve was then phase-folded to the 9.02 d period. No transit

signal above the noise was detected. We derive an upper limit of

![]() for the depth of any transit at a period of 9.02 d.

for the depth of any transit at a period of 9.02 d.

9 Orbital solutions

9.1 The 0.85-d period

Models of the internal structure of CoRoT-7b rely on the mass determination

which in turn hinges on the amplitude of the RV variations.

In Q09 the amplitude of CoRoT-7b was estimated to be 3.5 m s-1using two different approaches and this

corresponds to a planet mass of 4.8

![]() .

However, this value

was obtained after applying a correction term for the effects of the filtering

process to both techniques using simulated data.

The uncorrected pre-whitening

procedure amplitude was slightly higher at 4.2 m s-1 and

the harmonic filtering amplitude lower at 1.9 m s-1.

Clearly,

the amplitude of CoRoT-7b depends on how one removes the activity signal.

.

However, this value

was obtained after applying a correction term for the effects of the filtering

process to both techniques using simulated data.

The uncorrected pre-whitening

procedure amplitude was slightly higher at 4.2 m s-1 and

the harmonic filtering amplitude lower at 1.9 m s-1.

Clearly,

the amplitude of CoRoT-7b depends on how one removes the activity signal.

As an alternative approach to determining the RV amplitude of CoRoT-7b we took the results from Sect. 6. In this analysis we used only the RV data for which multiple measurements were made each night. A least squares sine fit to this data was made keeping the period fixed and allowing the nightly offset to vary. The final offsets were then subtracted from the individual nights and the data combined. This may be the best way to account for the RV variations of activity without any assumptions about its temporal behavior. An orbital solution was performed on all the residual RVs keeping the ephemeris, T0, fixed to the CoRoT transit time of 2 454 446.7311.

Table 13: Orbital parameters for the 0.85-d period.

Table 13 lists the orbital elements.

At first the nightly data were fit keeping the CoRoT transit period

of 0.8535 days. If we allow this parameter to vary we get a best fit to the

data with a period of 0.85359 days which is listed in the

table. Allowing the T0 to vary, but keeping the period fixed results

in T0 = 2 454 446.7330 a value very close to the CoRoT ephemeris.

Allowing the eccentricity to vary results in a best fit value of 0.08, but

with large error,

![]() 3.

We cannot exclude a slight eccentricity in the orbit, but given the

large variations due to activity and the additional companions, this may

be difficult to extract reliably from the RV data.

Figure 14 shows the zero-point corrected data phased to the

CoRoT transit ephemeris and a period of 0.85359. The solid line

represents the orbital solution.

3.

We cannot exclude a slight eccentricity in the orbit, but given the

large variations due to activity and the additional companions, this may

be difficult to extract reliably from the RV data.

Figure 14 shows the zero-point corrected data phased to the

CoRoT transit ephemeris and a period of 0.85359. The solid line

represents the orbital solution.

The derived K-amplitude is 5.04 ![]() 1.09 m s-1 which

results in a companion mass of 6.9

1.09 m s-1 which

results in a companion mass of 6.9 ![]() 1.4

1.4

![]() .

This is

slightly larger than the K-amplitude of 4.16

.

This is

slightly larger than the K-amplitude of 4.16 ![]() 0.27 m s-1(m = 5.75

0.27 m s-1(m = 5.75 ![]() 0.37

0.37

![]() )

by pre-whitening the full data set

(Q09). The K-amplitude from pre-whitening of the

full data set and the analysis of the subset RV data with

multiple measurements each night both suggest a slightly higher planet mass

than the 4.8

)

by pre-whitening the full data set

(Q09). The K-amplitude from pre-whitening of the

full data set and the analysis of the subset RV data with

multiple measurements each night both suggest a slightly higher planet mass

than the 4.8 ![]() 0.8

0.8

![]() of Q09, although all determinations

are consistent to within the errors.

of Q09, although all determinations

are consistent to within the errors.

|

Figure 14: (Top) Orbital solution for the 0.85-d period using the data with repeated nightly measurements and the appropriate zero-point offset applied. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

9.2 The 3.7-d period

RV residuals were produced by subtracting

all sine components except for f2 from the full RV data

set and an orbital solution calculated. In removing the

contribution of f1 the amplitude in Table 13 was used rather than the slightly higher

amplitude found in Table 1. The

derived amplitude is slightly lower than the one presented in Q09 (5.5 m s-1) that

removed f1 using the amplitude found in the pre-whitening procedure. In order to

estimate the range of velocity amplitudes for f2

a least squares fit to the original RV data was first made using

this frequency and the subsequent frequencies found in the

pre-whitening process sequentially subtracted. The range of amplitudes

for f2 during this

process ranged from 4.75 to 5.4 m s-1. An error of

![]() m s-1 was adopted which is

slightly more than the formal error of

m s-1 was adopted which is

slightly more than the formal error of

![]() m s-1 from the orbit fitting. Note that this formal error is much lower than for

the amplitude CoRoT-7b which was calculated using only a subset of the data.

m s-1 from the orbit fitting. Note that this formal error is much lower than for

the amplitude CoRoT-7b which was calculated using only a subset of the data.

Figure 15 shows the orbital solution the 3.7-day period. The orbital elements are listed in Table 14. A slight eccentricity is found, but this may well be an artifact due to the filtering process.

|

Figure 15: The RV residuals of CoRoT-7 after removing all components in Table 1 except for f2 and phased to the 3.7 d period (points). The orbital fit is shown as a line |

| Open with DEXTER | |

9.3 The 9-d period

The RV residuals were calculated after subtracting all sine components in Table 1 except for f3 and again using the

amplitude for f1 from Table 13. The range of possible amplitudes for

f3 during the pre-whitening procedure was 5.5-7.15 m s-1.

We thus adopted an error in the ampitude of

![]() m s-1,

larger than the formal error of

m s-1,

larger than the formal error of

![]() m s-1, but probably a

more realistic estimate. A best fit orbit allowing the eccentricity

to vary resulted in a slightly negative value. We therefore took a solution with

the eccentricity fixed to zero with an error of

m s-1, but probably a

more realistic estimate. A best fit orbit allowing the eccentricity

to vary resulted in a slightly negative value. We therefore took a solution with

the eccentricity fixed to zero with an error of

![]() .

.

Figure 16 shows the orbital solution to the RV residuals using the 9-day period. The orbital elements are listed in Table 15. Note the gap-like structures in the phase curve. This is undoubtedly due to the period being nearly an integer value of one day, i.e. our typical sampling rate.

Table 14: Orbital parameters for the 3.7-d period.

10 On the dynamical stablity of the 3-planet system.

We also investigated whether the 3-planet system would be dynamically stable. Although a stable system is no proof that all 3 planets exist, an unstable system would indicate that the additional planetary signals found in the HARPS data may arise from activity.

10.1 An ultra-compact planet system?

The stability of planetary systems involves multiple interactions of planets by

mutual perturbations

often involving interactions of resonances between more than two planets and various

components of

their motions. It is a stability for some time. As Lecar et al. (2001)

summarize it:

The solar system is not stable, it is just old!. Given the snapshot provided

by discovery orbital elements

we first briefly overview the gross/overall properties of the CoRoT-7 system by a

simple stability

indicator based on Hill-exclusion volumes. It requires non-overlapping cylindrical

volumes

of half-width

![]() ,

around each planet orbit. The Hill-radius to lowest

order is

,

around each planet orbit. The Hill-radius to lowest

order is

![]() ,

with

mi,ai denoting the mass and semi-major-axis of the ith planet,

respectively, and k is a factor of 4-15 depending on the number of planets, the

dynamical structure of

the system (masses, orbital elements), and the time-scale for stability under

consideration, cf.

e.g. Chambers et al. (1996) including a discussion on system stability with

long-term orbital

calculations.

Funk et al. (2010) show that for close-in systems, there are surprisingly large

volumes of phase

space for stable and planet-rich systems at periods of less than 10 days around

solar mass stars. These ultra compact systems can easily harbor 8 Super Neptunes for

,

with

mi,ai denoting the mass and semi-major-axis of the ith planet,

respectively, and k is a factor of 4-15 depending on the number of planets, the

dynamical structure of

the system (masses, orbital elements), and the time-scale for stability under

consideration, cf.

e.g. Chambers et al. (1996) including a discussion on system stability with

long-term orbital

calculations.

Funk et al. (2010) show that for close-in systems, there are surprisingly large

volumes of phase

space for stable and planet-rich systems at periods of less than 10 days around

solar mass stars. These ultra compact systems can easily harbor 8 Super Neptunes for

![]() and up to

and up to

![]() .

Funk et al. (2010)

determine a

factor of

.

Funk et al. (2010)

determine a

factor of ![]() that is necessary for stability in the present context -

3 planets, masses below Neptune's and few Ga timescales - and give

examples for it being sufficient including close-in systems with an

additional Jupiter-mass planet at

that is necessary for stability in the present context -

3 planets, masses below Neptune's and few Ga timescales - and give

examples for it being sufficient including close-in systems with an

additional Jupiter-mass planet at

![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() 50 days).

50 days).

An application of this Hill-stability estimator to the CoRoT-7 system is shown in

Fig. 17. The Hill-exclusion regions are outlined in a mass

versus

semi-major axis diagram for the system parameters determined here. Forbidden regions

for

other planets in a stable system are shown by shaded areas around every orbit. The

dark reddish

shaded area is for k=7, a secure upper bound to the Funk et al. (2010) results. The

larger,

light-blueish areas are for k=10 in order to approximately account for and

securely bound

uncertainties in the mass and semi-major axis determinations (6 and 3% resp. at ![]() )

and 15% for a possible orbital inclination

)

and 15% for a possible orbital inclination![]() ,

,

![]() of c and d.

The width of the stability exclusion regions is emphasized by two horizontal bars in

the

resp. color at the top. The stellar radius (yellow) and the Roche-limit (green) are

plotted as

vertical bars on the left.

of c and d.

The width of the stability exclusion regions is emphasized by two horizontal bars in

the

resp. color at the top. The stellar radius (yellow) and the Roche-limit (green) are

plotted as

vertical bars on the left.

|

Figure 16: The RV residuals of CoRoT-7 after removing all components in Table 1 except for f3 and phased to the 9.02 d period (points). The orbital fit is shown as a line |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 15: Orbital parameters for the 9.02-d period.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=14cm,clip]{14795fg17.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14795-10/Timg86.png)

|

Figure 17:

Synopsis and simple stability for the CoRoT-7 system. Planetary mass in

Earth-units

is plotted against the distance from the star in AU. Mass and semi-major axis

determinations

of this work (blue dots) and the discovery paper (green dots) are shown for the

CoRoT-7-system, together with their 1 and |

| Open with DEXTER | |

For comparison the mass-estimates of the discovery paper, Q09 are

shown with their 1 and ![]() error-ellipses to demonstrate that they

clearly provide less stringent stability constraints due to smaller mass values.

error-ellipses to demonstrate that they