| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A47 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913673 | |

| Published online | 08 June 2010 | |

A characterization of the NGC 4051 soft X-ray spectrum as observed by XMM-Newton

A. A. Nucita1 - M. Guainazzi1 - A. L. Longinotti2 - M. Santos-Lleo1 - Y. Maruccia3 - S. Bianchi4

1 - XMM-Newton Science Operations Centre, ESAC, ESA, PO Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de la

![]() ,

Madrid, Spain

,

Madrid, Spain

2 -

MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research 77 Massachusetts Avenue, NE80-6011 Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

3 -

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università del Salento, and INFN, Sezione di Lecce, CP 193, 73100 Lecce, Italy

4 -

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi Roma Tre, via della Vasca Navale 84, 00146 Roma, Italy

Received 16 November 2009 / Accepted 2 March 2010

Abstract

Context. Soft X-ray high resolution spectroscopy of obscured

AGNs shows a complex soft X-ray spectrum dominated by emission lines of

He and H-like transitions of elements from carbon to neon, as well as

L-shell transitions due to iron ions.

Aims. In this paper we characterize the XMM-Newton RGS

spectrum of the Seyfert 1 galaxy NGC 4051 observed during a low flux

state and infer the physical properties of the emitting and absorbing

gas in the soft X-ray regime.

Methods. X-ray high-resolution spectroscopy offers a powerful

diagnostic tool because the observed spectral features strongly depend

on the physical properties of matter (ionization parameter U, electron density ![]() ,

hydrogen column density

,

hydrogen column density ![]() ),

which in turn are tightly related to the location and size of the X-ray

emitting clouds. We carried out a phenomenological study to identify

the atomic transitions detected in the spectra. This study suggests

that the spectrum is dominated by emission from a photoionized plasma.

Then we used the photoionization code Cloudy to produce synthetic

models for the emission line component and the warm absorber observed

during phases of high intrinsic luminosity.

),

which in turn are tightly related to the location and size of the X-ray

emitting clouds. We carried out a phenomenological study to identify

the atomic transitions detected in the spectra. This study suggests

that the spectrum is dominated by emission from a photoionized plasma.

Then we used the photoionization code Cloudy to produce synthetic

models for the emission line component and the warm absorber observed

during phases of high intrinsic luminosity.

Results. The low state spectrum cannot be described by a single

photoionization component. A multi-ionization phase gas with an

ionization parameter in the range of

![]() and a column density

and a column density

![]() cm-2 is required, while the electron density

cm-2 is required, while the electron density ![]() remains unconstrained. A warm absorber medium is required by the fit with the parameters

remains unconstrained. A warm absorber medium is required by the fit with the parameters

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

The model is consistent with an X-ray emitting region at a distance

.

The model is consistent with an X-ray emitting region at a distance ![]()

![]() pc from the central engine.

pc from the central engine.

Key words: galaxies: Seyfert - galaxies: individual: NGC 4051 - techniques: spectroscopic

1 Introduction

It is commonly accepted that the center of active galaxies (Active

Galactic Nuclei -AGNs) hosts a massive black hole (with a mass in the

range 106-109 ![]() )

accreting the surrounding material via the formation of a disk. How the

energy released from the central engine interacts with the local

environment and contributes to the history of the host galaxy is one of

the crucial question of present astrophysical research.

In this respect, while the mechanisms of energy output in the form of

radiation and relativistic jets are quite well understood, it also

seems that the outflowing winds have an important role in the overall

energy budget.

Although the origin of these winds is still controversial, at our

present level of understanding the narrow-line regions, the inner part

of an obscuring torus (Blustin et al. 2005) and the black hole accretion disk (Elvis 2000) are all possible locations.

)

accreting the surrounding material via the formation of a disk. How the

energy released from the central engine interacts with the local

environment and contributes to the history of the host galaxy is one of

the crucial question of present astrophysical research.

In this respect, while the mechanisms of energy output in the form of

radiation and relativistic jets are quite well understood, it also

seems that the outflowing winds have an important role in the overall

energy budget.

Although the origin of these winds is still controversial, at our

present level of understanding the narrow-line regions, the inner part

of an obscuring torus (Blustin et al. 2005) and the black hole accretion disk (Elvis 2000) are all possible locations.

X-ray obscured AGNs (with an intrinsic column density

![]() cm-2) are not completely dark in the soft X-ray band. High resolution XMM-Newton

and Chandra observations revealed a complex spectrum dominated by

emission lines from He- and H-like transitions of elements from carbon

to neon as well as by L-shell transitions of Fe XVII to Fe XXI ions (Sako et al. 2000 a; Kinkhabwala et al. 2002; Sambruna et al. 2001; Armentrout et al. 2007). This gas, which shows the signature of a photoionization process (Kinkhabwala et al. 2002; Guainazzi & Bianchi 2007), is sometimes referred to as a warm mirror.

cm-2) are not completely dark in the soft X-ray band. High resolution XMM-Newton

and Chandra observations revealed a complex spectrum dominated by

emission lines from He- and H-like transitions of elements from carbon

to neon as well as by L-shell transitions of Fe XVII to Fe XXI ions (Sako et al. 2000 a; Kinkhabwala et al. 2002; Sambruna et al. 2001; Armentrout et al. 2007). This gas, which shows the signature of a photoionization process (Kinkhabwala et al. 2002; Guainazzi & Bianchi 2007), is sometimes referred to as a warm mirror.

In unobscured AGNs a modification of the output energy spectrum may

also occur as a consequence of absorption by a warm ionized gas along

the line of sight. The properties of these so called warm absorbers can

be summarized as follows: i) average ionization parameter in the range

![]() -3; ii) total column density in the range

-3; ii) total column density in the range

![]() -22 cm-2; iii) outflow velocities of hundred of km s-1 (see e.g. Blustin et al. 2005, but also Steenbrugge et al. 2009). Evidence of a multi-phase warm absorber gas was also recently reported for Mrk 841 (Longinotti et al. 2010).

-22 cm-2; iii) outflow velocities of hundred of km s-1 (see e.g. Blustin et al. 2005, but also Steenbrugge et al. 2009). Evidence of a multi-phase warm absorber gas was also recently reported for Mrk 841 (Longinotti et al. 2010).

In general, detecting warm mirror signatures is easier in sources in low flux states, because the emission features are not outshone by the continuum radiation. This was the case for the Seyfert 1 galaxy Mrk 335, whose soft X-ray spectrum resembled the spectra of obscured AGNs when the source was observed at low state (Longinotti et al. 2008), but does not show any evidence of a warm absorber in the high flux state (Longinotti et al. 2007).

The overall properties of the warm mirror (even if it is poorly constrained) and the warm absorber (as described above) are similar so that there is the possibility that they represent the same physical system. Conversely, the interplay between the warm absorber and warm mirror regimes is best studied in sources that display both components.

The source NGC 4051, a narrow-line Seyfert galaxy at the

redshift of 0.00234, was at the center of many past investigations in

the X-ray band because it offers a unique laboratory where to test

present theories and models about the physics of AGNs. The X-ray

emission is characterized by rapid variations (Lamer et al. 2003; Ponti et al. 2006) sometimes showing periods of low activity (see Lawrence et al. 1987 and Uttley et al. 1999). Its power spectral distribution (PSD) in high state resembles the behavior of a galactic black hole system (McHardy et al. 2004). At high X-ray flux, the spectrum of the galaxy is characterized by a power law with photon index

![]() -2

which becomes harder above 7 keV where a reflection component from

cold matter has been observed. On long time-scales, the X-ray light

curve of NGC 4051 shows low state flux periods of several months during

which the spectrum in the energy range 2-10 keV becomes harder (

-2

which becomes harder above 7 keV where a reflection component from

cold matter has been observed. On long time-scales, the X-ray light

curve of NGC 4051 shows low state flux periods of several months during

which the spectrum in the energy range 2-10 keV becomes harder (

![]() )

and shows a strong iron

)

and shows a strong iron ![]() line (as found by Guainazzi et al. 1998 in Beppo-SAX data). A soft `X-ray excess is also evident.

line (as found by Guainazzi et al. 1998 in Beppo-SAX data). A soft `X-ray excess is also evident.

As reported by Ogle et al. (2004),

the high state X-ray spectrum of NGC 4051 in the soft band is a

combination of continuum and emission line components. Curvature in the

spectrum cannot be explained with simple models, i.e. a single power

law or a black body, because an ionized absorber-emitter has to be

taken into account as well. In this context, Krongold et al. (2007)

showed that the evolution in time of the properties of the warm

absorber can constrain the physical parameters of the absorbing gas. In

particular they find that at least two different ionization components

are required with matter densities of ![]() 106 cm-3 and

106 cm-3 and ![]() 107 cm-3,

thus placing the warm absorber in the vicinity of the accretion-disk.

Dynamical arguments permit us to infer that the warm absorber gas

originates in a radiation-driven high-velocity outflow in accretion

disk instabilities (Krongold et al. 2007).

107 cm-3,

thus placing the warm absorber in the vicinity of the accretion-disk.

Dynamical arguments permit us to infer that the warm absorber gas

originates in a radiation-driven high-velocity outflow in accretion

disk instabilities (Krongold et al. 2007).

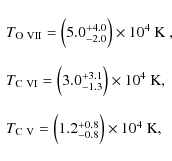

On the other hand, as shown by Pounds et al. (2004),

the low state flux spectrum of NGC 4051 is dominated by narrow emission

lines and radiative recombination continua (RRC) from hydrogenic and

He-like carbon, oxygen, neon and nitrogen. To be specific, a fit to the

identified RRCs yields a mean temperature for the emitting gas of

![]() K,

which favors a scenario invoking a photoionization process. In this

case, the soft X-ray spectrum of NFG 4051 in low state is similar to

that observed for the prototype Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068 (see Kinkhabwala et al. 2002).

K,

which favors a scenario invoking a photoionization process. In this

case, the soft X-ray spectrum of NFG 4051 in low state is similar to

that observed for the prototype Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068 (see Kinkhabwala et al. 2002).

Below we do not repeat the analysis of the EPIC data but refer to Pounds et al. (2004)

for more details on the main results obtained in the energy band

0.3-10 keV. We only say that a comparison between the EPIC PN data

for the 2001 and 2002 observations shows that the high state

observation flux level is a factor ![]() 5

greater with respect to the low state. Furthermore, the spectrum shows

a gradual flattening of the continuum slope from 3 keV up to

6.4 keV. It was also noted that when the fit to the

0.3-10 keV band continuum is extrapolated down in the soft X-ray

(0.3-3 keV) a strong excess appears in both the two observations,

and as is clear from the RGS spectrum, it can be explained by a

blending effect of fine structures (emission lines).

5

greater with respect to the low state. Furthermore, the spectrum shows

a gradual flattening of the continuum slope from 3 keV up to

6.4 keV. It was also noted that when the fit to the

0.3-10 keV band continuum is extrapolated down in the soft X-ray

(0.3-3 keV) a strong excess appears in both the two observations,

and as is clear from the RGS spectrum, it can be explained by a

blending effect of fine structures (emission lines).

Here we first conducted a phenomenological study of the emission lines identified in the spectrum of NGC 4051 and compare our results with those known in literature. We further compared the RGS emission line spectrum with synthetic spectra generated with the photoionization code Cloudy 8 (Ferland et al. 1998). For this purpose we followed a similar approach as in Armentrout et al. (2007) (to which we refer for more details) on NGC 4151.

The paper is structured as follows: in Sect. 2 we briefly describe the reduction of the XMM-Newton data set and describe our phenomenological analysis of the soft X-ray spectrum of NGC 4051. In Sects. 3 and 4 we give details on the Cloudy model developed and address some conclusions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=13cm,clip]{13673f1.ps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg22.png)

|

Figure 1: Fluxed RGS spectrum of

NGC 4051 (low state). The first order spectra of the two RGS cameras

were combined and the resulting spectrum smoothed with a triangular

kernel. The identified lines are labeled with the corresponding ion

transition name and vertical dashed lines (the big dips at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2 A phenomenological study of the low state of NGC 4051: data reduction and line identification

The source NGC 4051 (

![]() and

and

![]() )

was observed by the XMM-Newton satellite on two occasions: on May 2001 for

)

was observed by the XMM-Newton satellite on two occasions: on May 2001 for ![]() 122 ks and on November 2002 for

122 ks and on November 2002 for ![]() 52 ks. While the former observation coincided with a period where the central engine was bright (with luminosity of

52 ks. While the former observation coincided with a period where the central engine was bright (with luminosity of

![]() erg s-1 in the 0.3-10 keV, Pounds et al. 2004), the latter corresponded to a low state X-ray flux (corresponding to a luminosity of

erg s-1 in the 0.3-10 keV, Pounds et al. 2004), the latter corresponded to a low state X-ray flux (corresponding to a luminosity of

![]() erg s-1 in the 0.3-10 keV, Pounds et al. 2004) due to a low nuclear activity. This observation was conducted

erg s-1 in the 0.3-10 keV, Pounds et al. 2004) due to a low nuclear activity. This observation was conducted ![]() 20 days after the onset of the low state (Pounds et al. 2004).

Below we focus on the low state data analysis, because the warm

absorber observed at high state was already well studied with physical

models (Ogle et al. 2004; Krongold et al. 2007; Steenbrugge et al. 2009).

On the contrary, no attempt has yet been made to model the warm mirror

in the low state with a self consistent physical model.

20 days after the onset of the low state (Pounds et al. 2004).

Below we focus on the low state data analysis, because the warm

absorber observed at high state was already well studied with physical

models (Ogle et al. 2004; Krongold et al. 2007; Steenbrugge et al. 2009).

On the contrary, no attempt has yet been made to model the warm mirror

in the low state with a self consistent physical model.

The ODF files (OM, MOS, PN and RGS) were processed with the XMM-Science Analysis System (SAS version 8). Hence the raw data were reduced using SAS tasks with standard settings and the most update calibration files to produce the source and background spectra as well as the corresponding response matrices for the RGS cameras.

We used XSPEC 12.5.1 (Arnaud et al. 2007) for our quantitative analysis and adopted the cosmological parameters H0=70 km s-1 Mpc-1,

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

To study the soft X-ray spectra of NGC 4051 in more detail, we then examined the first order spectra obtained by the XMM-Newton gratings. The spectral resolution of RGS in the first order spectrum is

![]() mÅ and the calibration in wavelength is accurate up to 8 mÅ corresponding to

mÅ and the calibration in wavelength is accurate up to 8 mÅ corresponding to

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]() km s-1 at 35 Å (XMM-Newton Users Handbook 2009). Below we use the unbinned RGS 1 and RGS 2 spectra for the quantitative analysis. In Fig. 1, we show the fluxed RGS spectrum in the wavelength range 5-38 Å.

km s-1 at 35 Å (XMM-Newton Users Handbook 2009). Below we use the unbinned RGS 1 and RGS 2 spectra for the quantitative analysis. In Fig. 1, we show the fluxed RGS spectrum in the wavelength range 5-38 Å.

As can be clearly seen, the 2002 RGS spectrum of NGC 4051 shows

an unresolved continuum with a predominance of emission lines (see for

comparison the RGS spectrum of NGC 1068 presented in Kinkhabwala et al. 2002).

By contrast, the high state RGS spectra of the same source show a

higher continuum flux level with a pronounced curvature around ![]() 15 Å and several absorption features (Pounds et al. 2004) typical of a warm absorber. Interestingly, the N VI, O VII and Ne IX forbidden lines are seen in both observations with the same flux level (Pounds et al. 2004).

15 Å and several absorption features (Pounds et al. 2004) typical of a warm absorber. Interestingly, the N VI, O VII and Ne IX forbidden lines are seen in both observations with the same flux level (Pounds et al. 2004).

The phenomenological spectral analysis follows the local fits method described in Guainazzi & Bianchi (2007). In particular, the unbinned spectra are divided in intervals of ![]() 100 channels

wide and Gaussian profiles are used to account for all identified

emission lines, with the line centroid energy as the only free

parameter of the fit.

100 channels

wide and Gaussian profiles are used to account for all identified

emission lines, with the line centroid energy as the only free

parameter of the fit.

Analogously, free-bound transitions (i.e. Radiative

Recombination Continua) were also modeled as Gaussian profiles with

free line width. Best-fit values of these widths are reported in

Table 2 together with their errors. The local continuum was modeled as a power law with a fixed photon index

![]() and free normalization. For line triplets and for emission lines close

to free-bound transitions, the relative distance between the central

energies was frozen to the value predicted by atomic physics.

and free normalization. For line triplets and for emission lines close

to free-bound transitions, the relative distance between the central

energies was frozen to the value predicted by atomic physics.

We used the C-statistic as the estimator of the goodness of the performed fit (Cash 1979). For any line under investigation, the emission feature was considered detected

if, when repeating the fit without any Gaussian profile, we obtained a

value of the C-statistic which differed from the previous one by at

least 2.3, corresponding to the 68![]() confidence level (or, equivalently, 1

confidence level (or, equivalently, 1![]() for one interesting parameter; Arnaud et al. 2007).

for one interesting parameter; Arnaud et al. 2007).

The results of the phenomenological fit to the emission lines are reported in Table 1.

We recall that the fluxes of the identified emission lines were

estimated integrating over the Gaussian line profiles with which the

emission features are modeled. This operation resulted in flux values

somehow higher (up to a factor of ![]() 1.5) than those reported in Pounds et al. (2004)

even if the corresponding measured equivalent widths are fully

consistent with the values quoted in the above mentioned paper. The

origin of the discrepancy remains unknown.

1.5) than those reported in Pounds et al. (2004)

even if the corresponding measured equivalent widths are fully

consistent with the values quoted in the above mentioned paper. The

origin of the discrepancy remains unknown.

Here we give the best-fit parameters for the transitions identified in the soft X-ray spectrum of NGC 4051.

For those lines that were not identified (i.e.

![]() ), but which are part still of triplet features, we give the upper limits to the corresponding flux value.

We detected no evidence for either inflows or outflows, with an upper limit on the velocity of

), but which are part still of triplet features, we give the upper limits to the corresponding flux value.

We detected no evidence for either inflows or outflows, with an upper limit on the velocity of ![]() 200 km s-1, consistent with that estimated by Pounds et al. (2004).

This was calculated from the full width half maximum of the

distribution of residual velocity as derived from the difference

between the expected

and the measured laboratory wavelengths (see Fig. 2 and also Table 1).

200 km s-1, consistent with that estimated by Pounds et al. (2004).

This was calculated from the full width half maximum of the

distribution of residual velocity as derived from the difference

between the expected

and the measured laboratory wavelengths (see Fig. 2 and also Table 1).

Table 1: Best-fit parameters for the transitions identified in the soft X-ray spectrum of NGC 4051.

Table 2: The same as in Table 1 but for the identified RRCs.

2.1 Radiative recombination continua (RRC)

The electron temperature ![]() can be inferred by studying the profiles of the radiative recombination

continua (RRC). In the RGS spectrum of NGC 4051 the RRCs detected with

can be inferred by studying the profiles of the radiative recombination

continua (RRC). In the RGS spectrum of NGC 4051 the RRCs detected with

![]() correspond to O VII, C V and C VI (see Table 2 for details). Expressing the temperature widths in eV to

correspond to O VII, C V and C VI (see Table 2 for details). Expressing the temperature widths in eV to

![]() (Liedhal 1999), we estimate them to be

(Liedhal 1999), we estimate them to be

|

(1) |

respectively, so that the average gas temperature is

In this phenomenological analysis, we used Gaussian profiles to fit the RRC features, which are in principle asymmetric. Still we verified that the use of a more appropriate model, as e.g. redge in XSPEC, gives consistent results.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg94.png)

|

Figure 2: Distribution of residual velocity for all lines in Table 1 with respect to the cosmological one. Note that the observed shifts are consistent with the cosmological ones, i.e. no outflow or inflow is observed. The solid line represents the Gaussian best-fit to the data. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 3: Zoom around the O VII triplet lines in the low flux state. The emission lines correspond to the f, i and r components, respectively. Only an upper limit to the resonance line r can be obtained (see text). The solid line represents the best-fit obtained with a power law + Gaussian lines model (details in text). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 He-like triplet diagnostic

We detected the most intense lines of He-like ions in the range 5-35 Å. The transitions between the n=2 shell and the n=1 ground state shell as the resonance line (r: 1s2 1S0-1s2p 1P1), the two inter-combination lines (i: 1s21S0-1s2p 3P2,1, often blended) and the forbidden line (f: 1s21S0-1s2s3S1) were detected. As demonstrated by Porquet & Dubau (2000) the relative emission strength of the r, i and f lines are good indicators of the physical conditions of density and temperature of the gas. Using standard notation we defined the ratios R=f/i, L=r/i and G=(f+i)/r (Porter & Ferland. 2007). Figure 3 shows the triplet of the O VII complex (forbidden, inter-combination and resonance lines) locally fitted by a power law and three Gaussian. In this case, following the phenomenological fit approach described in the previous section, we only had a measurement for the fluxes of the f and i components (see Table 1).

With the flux measurements quoted in Table 1, the previous relations give

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

Analogously, for the NVI triplet we get

.

Analogously, for the NVI triplet we get

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() (poorly constrained because we only got an upper limit to the r line flux value), respectively. For Ne IX we had a lower limit only on the

(poorly constrained because we only got an upper limit to the r line flux value), respectively. For Ne IX we had a lower limit only on the

![]() ratio, while the ratio of the O VIII Ly-

ratio, while the ratio of the O VIII Ly-![]() to the O VII forbidden intensity lines results in

to the O VII forbidden intensity lines results in

![]() .

These line ratios are consistent with the results by Pounds et al. (2004).

.

These line ratios are consistent with the results by Pounds et al. (2004).

2.3 Results of the phenomenological study: evidence of photoionized gas

The results obtained from the phenomenological study allow us to

highlight some considerations on the physical conditions of the X-ray

emitting gas in NGC 4051. Indeed, according to the study of Porquet & Dubau (2000),

a value of the G ratio higher than 4 is a strong indication of a

photoionized gas. An estimate of the gas electron density ![]() can be done when the other two line ratios L and R are taken into account. In the particular case of the O VII triplet line ratios quoted above, the electron density is constrained to be

can be done when the other two line ratios L and R are taken into account. In the particular case of the O VII triplet line ratios quoted above, the electron density is constrained to be

![]() cm-3 for a pure photoionized gas (Porquet & Dubau 2000).

Note however that the line intensities obtained from the

phenomenological study described above do not account for a warm

absorber, which is not taken into account in the model.

cm-3 for a pure photoionized gas (Porquet & Dubau 2000).

Note however that the line intensities obtained from the

phenomenological study described above do not account for a warm

absorber, which is not taken into account in the model.

An additional constraint on the electron density value can be obtained noting that the XMM-Newton observation of NGC 4051 in its low state occurred ![]() 20 days after the source entered this regime.

Because the O VII triplet line intensity is consistent with that measured during high flux states (Pounds et al. 2004), it is believed that the recombination time of the O VII

is larger than 20 days,thus implying (for a gas temperature of

20 days after the source entered this regime.

Because the O VII triplet line intensity is consistent with that measured during high flux states (Pounds et al. 2004), it is believed that the recombination time of the O VII

is larger than 20 days,thus implying (for a gas temperature of ![]() 104 K) a more stringent constraint on the electron density of

104 K) a more stringent constraint on the electron density of

![]() cm-3 (Pounds et al. 2004).

cm-3 (Pounds et al. 2004).

3 Fitting the spectra with the photoionization code Cloudy

3.1 General properties of the model

The results of the phenomenological analysis in Sect. 2 show that the bulk of the spectrum, measured by the RGS during the X-ray low state in NGC 4051, is dominated by photoionization as already suggested by other authors (see e.g. Pounds et al. 2004).

In this section we use the photoionization code Cloudy (Ferland et al. 1998) for modeling the overall spectrum of NGC 4051 in its low state assuming a plane parallel geometry with the central engine shining on the inner face of the cloud with a flux density depending on the ionization parameter U.

The spectrum produced by a photoionized nebula critically depends on

the spectral energy distribution (SED) of the ionizing continuum. Below

we adopt the AGN SED as in Korista et al. (1997b).

In a typical AGN the observed continuum can be well represented by a

SED characterized by several components: a big blue bump with

temperature

![]() K (1 Ryd), a power law with a low energy exponential cut-off in the infrared region at

K (1 Ryd), a power law with a low energy exponential cut-off in the infrared region at

![]() Ryd; in the X-ray band (1.36 eV-100 keV) the SED is

well approximated by a power law with an exponential cut-off for

energies lower than 1 Ryd; finally, for energies greater than

100 keV an exponential fall as

Ryd; in the X-ray band (1.36 eV-100 keV) the SED is

well approximated by a power law with an exponential cut-off for

energies lower than 1 Ryd; finally, for energies greater than

100 keV an exponential fall as

![]() is usually assumed . We also included in the modeling the cosmic

microwave background so that the incident continuum has a non-zero

intensity for long wavelengths. Hence the AGN spectrum is described by

the law

is usually assumed . We also included in the modeling the cosmic

microwave background so that the incident continuum has a non-zero

intensity for long wavelengths. Hence the AGN spectrum is described by

the law

|

(2) |

where

To determine

![]() and

and

![]() ,

we used the Epic data corresponding to the NGC 4051 high state

observation. The resulting 0.2-10 keV energy band spectrum was

fitted with a photoelectrically absorbed power law model within XSPEC,

thus allowing us to measure

,

we used the Epic data corresponding to the NGC 4051 high state

observation. The resulting 0.2-10 keV energy band spectrum was

fitted with a photoelectrically absorbed power law model within XSPEC,

thus allowing us to measure

![]() and

and

![]() erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1, respectively.

erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1, respectively.

From the OM instrument we estimated the aperture photometry of the

target in the UVM2 filter (centered at 2310 Å) obtaining a flux

density of

![]() erg s-1 cm-2 Å-1. From the flux densities at 2 keV and 2500 Å, the X-UV flux density ratio results in

erg s-1 cm-2 Å-1. From the flux densities at 2 keV and 2500 Å, the X-UV flux density ratio results in

![]() .

.

Once the AGN SED (erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1) is known, it is straightforward to show that the number of hydrogen-ionizing photons Q![]() , the electron density

, the electron density ![]() and the dimensionless ionization parameter U are related by

and the dimensionless ionization parameter U are related by

![]() with r

the distance between the central engine and the innermost illuminated

layer of the clouds. Here we require that integrating over the SED

(between 13.6 eV and 13.6 keV) we get the ionizing luminosity

with r

the distance between the central engine and the innermost illuminated

layer of the clouds. Here we require that integrating over the SED

(between 13.6 eV and 13.6 keV) we get the ionizing luminosity

![]() erg s-1 (Ogle et al. 2004). In Fig. 4 we compare the SED used in this paper (solid line) with that given in Ogle et al. (2004). We recall that the dimensionless ionization parameter U

does not depend on the flux below 13.6 eV. The two spectral energy

distributions give rise to comparable integrated fluxes in the

0.3-10 keV energy band (within a few percent).

erg s-1 (Ogle et al. 2004). In Fig. 4 we compare the SED used in this paper (solid line) with that given in Ogle et al. (2004). We recall that the dimensionless ionization parameter U

does not depend on the flux below 13.6 eV. The two spectral energy

distributions give rise to comparable integrated fluxes in the

0.3-10 keV energy band (within a few percent).

Note also that through the well known definitions of the ionizing luminosity

![]() ,

of the number of ionizing photons Q (Ferland et al. 1998) and the used SED

,

of the number of ionizing photons Q (Ferland et al. 1998) and the used SED ![]() ,

it is possible to estimate a useful conversion relation between the dimensionless ionization parameter U and the ionization parameter

,

it is possible to estimate a useful conversion relation between the dimensionless ionization parameter U and the ionization parameter ![]() as given in Tarter et al. (1969), i.e.

as given in Tarter et al. (1969), i.e.

![]() erg cm s-1.

erg cm s-1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f4.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg127.png)

|

Figure 4: SED used in the paper (solid line). For comparison we also give (dashed line) the SED given in Ogle et al. (2004). This was taken from the NED database and is likely to contain contamination from the hosting galaxy. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

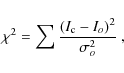

3.2 Fit to the RGS spectrum

Assuming the standard AGN continuum described above, we generated a

grid of reflected spectra from a photoionized nebula, varying the

ionization parameter ![]() ,

the electron density

,

the electron density

![]() and the total column density

and the total column density

![]() .

The free parameters spanned the ranges

.

The free parameters spanned the ranges

![]() ;

;

![]() and

and

![]() in steps of 0.1 dex, respectively.

in steps of 0.1 dex, respectively.

Initially we extracted the line intensities from these simulations for

all lines detected in the soft spectrum of NGC 4051. Hence, we tried to

determine the best model that can describe the RGS line spectrum in the

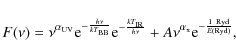

whole 5-35 Å band. Following the procedure described in Longinotti et al. (2008), we calculated the value of the merit function for each grid model

|

(3) |

where Io is the intensity of each of the identified lines (with statistical error

Minimizing the merit function quoted above gives a best-fit model (

![]() with degrees of freedom

with degrees of freedom ![]() )

corresponding to the parameter values

)

corresponding to the parameter values

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

A quantitative measure of the fit goodness for the used model is given by the Chi-square Probability Function

.

A quantitative measure of the fit goodness for the used model is given by the Chi-square Probability Function

![]() as defined in Press et al. (2004). If the single phase component model is

the true representation of the data, the probability to obtain the observed

as defined in Press et al. (2004). If the single phase component model is

the true representation of the data, the probability to obtain the observed ![]() value is as high as

value is as high as

![]() .

In this case, the model consisting of a single ionization state can be statistically rejected.

.

In this case, the model consisting of a single ionization state can be statistically rejected.

We therefore investigated more complex models, including an additional warm mirror and one warm absorber covering the combination of emitting components. For this approach to be fruitful the constraints provided by the continuum shape are crucial. Below we will fit the whole RGS spectrum globally.

3.3 Global fit to the RGS spectrum

We generated additive and multiplicative fits tables (with the same

grid of parameters as before) to account for both the emission and

absorption features observed in the RGS spectrum, and imported them

within XSPEC as described in Porter et al. (2006). Our final model can be described by the formula

![]() .

Here, mtab and atab

indicate the warm absorber component and the reflected component part

of the spectrum depending on the electron density, hydrogen column

density and ionization parameter, respectively. In the model, the

redshift of each component is fixed to the cosmological value due to

the lack of measurable velocity shifts from the phenomenological

analysis (Fig. 2), while

all the other parameters are free to vary. In the fit procedure we

fixed the column density of neutral hydrogen to the average value

observed in the Galaxy along the line of sight to NGC 4051, i.e.

.

Here, mtab and atab

indicate the warm absorber component and the reflected component part

of the spectrum depending on the electron density, hydrogen column

density and ionization parameter, respectively. In the model, the

redshift of each component is fixed to the cosmological value due to

the lack of measurable velocity shifts from the phenomenological

analysis (Fig. 2), while

all the other parameters are free to vary. In the fit procedure we

fixed the column density of neutral hydrogen to the average value

observed in the Galaxy along the line of sight to NGC 4051, i.e.

![]() cm-2 (Dickey & Lockman 1990).

cm-2 (Dickey & Lockman 1990).

The fit does not formally depend on values of

![]() cm-3,

which is expected because the ratios of the He-like triplets are

insensitive to the electron density in this region of the space

parameter (Porquet & Dubau 2000). Given the constraint on this parameter derived from the source time variability, we fixed its value to 105 cm-3 hereafter.

cm-3,

which is expected because the ratios of the He-like triplets are

insensitive to the electron density in this region of the space

parameter (Porquet & Dubau 2000). Given the constraint on this parameter derived from the source time variability, we fixed its value to 105 cm-3 hereafter.

We recursively increased the number of Cloudy additive components until this operation resulted in a statistically significant improvement of the fit quality. We found that two emission and one absorption components are required to fit the data. In particular, the final model corresponds to a value of the C-statistic of 6300 with 5178 d.o.f. and the model parameters are given in Table 4. Conversely, when the warm absorber component is not taken into account the fit visibly worsens and converges to a C-statistic value of 9452 with 5182 d.o.f. In this case, the line intensities corresponding to the He-like transitions are not correctly estimated, with specifically the recombination line of the O VII triplet well over-estimated (see Fig. 5).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13673f5.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg148.png)

|

Figure 5: Comparison of a model with two emission components (solid line) with the observed RGS spectrum (zoom around the O VII triplet). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We then extracted the line fluxes predicted by the best-fit model and compared them with the observations. In Fig. 6, we show with filled squares the intensities of all observed (see Table 1) and simulated (triangles) lines once normalized to the O VIII Ly-![]() flux. The lower panel of the same figure shows the residuals between

observation and theory. Note that the simulation underestimates the

contribution of the Fe XVII transitions, because the Cloudy database is inaccurate for the corresponding

atomic parameters (see e.g. Bianchi et al. 2010). The normalized intensities of the observed lines as well as the Cloudy predictions are also reported in Table 3 for clarity with the missing value of the Fe XVII transition.

flux. The lower panel of the same figure shows the residuals between

observation and theory. Note that the simulation underestimates the

contribution of the Fe XVII transitions, because the Cloudy database is inaccurate for the corresponding

atomic parameters (see e.g. Bianchi et al. 2010). The normalized intensities of the observed lines as well as the Cloudy predictions are also reported in Table 3 for clarity with the missing value of the Fe XVII transition.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13673f6.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg149.png)

|

Figure 6:

Intensities of the observed (filled squares) and simulated (triangles)

lines corresponding to the best-fit and normalized to the O VIII Ly- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3:

Intensities of the observed lines and of those simulated by Cloudy corresponding to the best-fit and normalized to the O VIII Ly-![]() flux (see text and Fig. 6 for more details).

flux (see text and Fig. 6 for more details).

In Table 4 we give the relevant quantities estimated from the fit procedure (i.e. ![]() ,

,

![]() and U) together with their respective errors at the 90

and U) together with their respective errors at the 90![]() confidence level for one interesting parameter. The 5-35 Å low-state spectrum of NGC 4051 is plotted in Fig. 7

with the best-fit Cloudy model superimposed on the observed RGS 1

(red) and RGS 2 (black) data and residuals in the lower part of

each panel.

confidence level for one interesting parameter. The 5-35 Å low-state spectrum of NGC 4051 is plotted in Fig. 7

with the best-fit Cloudy model superimposed on the observed RGS 1

(red) and RGS 2 (black) data and residuals in the lower part of

each panel.

Note that to estimate the covering factor of the source, we

extracted the luminosity of the most prominent emission line, O VII (f),

as predicted by Cloudy. For the two reflection components included in

our model, we simulated the expected spectrum the SED described in

Sect. 3.1 and fixing the electron density ![]() and hydrogen column density

and hydrogen column density ![]() to the best-fit values given in Table 4. In addition, the SED was normalized to the ionizing luminosity

to the best-fit values given in Table 4. In addition, the SED was normalized to the ionizing luminosity

![]() erg s-1 (Ogle et al. 2004).

Hence we fixed the distance from the source to the inner shell of the

cloud to the lower values reported in Table 4 for each of the

reflection components, i.e.

erg s-1 (Ogle et al. 2004).

Hence we fixed the distance from the source to the inner shell of the

cloud to the lower values reported in Table 4 for each of the

reflection components, i.e.

![]() pc and

pc and

![]() pc for the low and high

component, respectively. After we defined the luminosity of the source,

the emission line luminosities were predicted by Cloudy (see e.g. Ferland 2008).

pc for the low and high

component, respectively. After we defined the luminosity of the source,

the emission line luminosities were predicted by Cloudy (see e.g. Ferland 2008).

With a redshift of 0.00234, the expected total intensity of the O VII (f) line is ![]()

![]() erg s-1 cm-2. Assuming a filling factor of unity, the ratio of the observed O VII (f) intensity (see Table 1) to the Cloudy expected value gives an estimate of the covering factor value, which turns out to be

erg s-1 cm-2. Assuming a filling factor of unity, the ratio of the observed O VII (f) intensity (see Table 1) to the Cloudy expected value gives an estimate of the covering factor value, which turns out to be ![]() 0.14.

0.14.

![\begin{figure}

\par\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f7a.eps}...

...dth=6cm,angle=-90,clip]{13673f7f.ps} }\vspace*{-2mm}

\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg161.png)

|

Figure 7: The 5-35 Å RGS 1 (red data points) and RGS 2 (black data points) spectra are shown together with the best-fit Cloudy model described in the text and corresponding to the physical parameters reported in Table 4. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Discussion

Most of the information on the physics and geometry of gas in AGNs is

inferred by means of optical spectroscopy and imaging techniques with

which it was shown that the AGN central high energy emission is the

main source of ionizing photons with an occasional contribution from

collisionally ionized plasma. In the last years X-rays observations

acquired an important role in AGN studies particularly since Chandra

showed the existence, at least for Seyfert 2 galaxies, of extended

(a few kpc) X-ray emission (Bianchi et al. 2006)

similarly to what was observed in the optical band.

High resolution spectroscopy in the soft X-ray band (0.2-2 keV)

confirms the overall scenario, and photoionization seems to be

the dominant ionization mechanism which results in a spectrum

characterized by recombination lines from He- and H-like transitions of

C to Si elements and by Fe-L transitions. In this respect, X-ray

high-resolution spectroscopy offers a powerful diagnostic tool because

the observed spectral features strongly depend on the physical

properties of matter (ionization parameter U, electron density ![]() ,

hydrogen column density

,

hydrogen column density ![]() as well as size and location of the emitting clouds).

as well as size and location of the emitting clouds).

The Seyfert 1 object NGC 4051 shows a very rich emission line X-ray

spectrum when observed in low-flux state. According to the analysis we

conducted on the XMM-Newton RGS data, the observed soft X-ray features originate in a low-density photoionized gas.

In order to constrain the physical properties of the photoionized gas, we simulated synthetic spectra via the Cloudy software (Ferland et al. 1998)

and compared them to the RGS data with standard minimization

techniques. We found that to describe the overall soft X-ray spectrum,

at least a three-phase gas is required (two emission components and one

warm absorbing component). Referring to the emission components

respectively as low and high ionization components, our fit procedure gave us their physical properties. For the low component we have

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() and for the high component we have

and for the high component we have

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

Using Cloudy we get for the electron density

.

Using Cloudy we get for the electron density ![]() an upper limit of

an upper limit of

![]() ,

which reduces to

,

which reduces to

![]() when the recombination time scale of O VII

is taken into account. Even if the warm absorber gas seems to be

required by our fit procedure, its parameters are poorly constrained.

Thus it is characterized by

when the recombination time scale of O VII

is taken into account. Even if the warm absorber gas seems to be

required by our fit procedure, its parameters are poorly constrained.

Thus it is characterized by

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

.

Table 4: Best-fit parameters for the three components of the adopted Cloudy model used to fit the RGS data.

This technique was successfully applied before to the Seyfert 1 Mrk 335 and the Seyfert 2/starburst galaxy NGC 1365 (Guainazzi et al. 2009; Longinotti et al. 2008).

The main difference is that NGC 4051 is characterized by a strong

warm absorber component in the high flux state that is still affecting

the spectrum even when the nuclear flux is attenuated. Indeed, we found

out in our analysis of the low flux state data that the effect of the

line of sight medium is not negligible, particularly not in the

modeling of the resonance line of the O VII triplet (see Fig. 5)

which is close to several absorption features. For example, the

resonance line could be weakened by the same line in absorption![]() (see e.g. Krongold et al. 2007).

Nonetheless, the physical parameters of the warm absorber cannot be

well-constrained by the analysis of the low flux state data (see Table

4).

(see e.g. Krongold et al. 2007).

Nonetheless, the physical parameters of the warm absorber cannot be

well-constrained by the analysis of the low flux state data (see Table

4).

The average distance r of each of the photoionized

plasma-emitting components from the nuclear source can be estimated by

the definition of the ionization parameter U after normalizing to the ionization luminosity

![]() .

However, our results are insensitive to values of the electron density

.

However, our results are insensitive to values of the electron density ![]() lower than 105 cm-3. In this limit, we can only determine a lower limit of the X-ray-emitting gas location (Table 4).

lower than 105 cm-3. In this limit, we can only determine a lower limit of the X-ray-emitting gas location (Table 4).

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f8...

...}

\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f8b.eps} }}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg184.png)

|

Figure 8: The cartoon shows qualitatively the location of the X-ray emitting and absorbing material (see text for details). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The analysis carried out in this paper allowed us to identify two

ionization states for the line emitting gas and one warm absorber

medium. It is interesting to note that

- The X-ray emitting region can be placed at a distance of

pc.

pc.

This is also naturally expected as a consequence of projection effects: as shown by Schmitt et al. (2003), who studied a sample of 60 Seyfert galaxies with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Seyfert 1 narrow-line regions objects are more circular and compact than those in the Seyfert 2 galaxies, with the Seyfert 2 subsample characterized by more elongated shapes. This agrees well with the unified picture according to which the conical narrow-line region of a Seyfert 1 galaxy is observed close to the axis of symmetry, while that of a Seyfert 2 galaxy is observed from an orthogonal line of sight.

Furthermore, the scale-length found in this paper is consistent

with the inner radius of the torus in NGC 4051 as determined by Blustin et al. (2005), i.e.

![]() pc.

pc.

- The NGC 4051 low state warm absorber is poorly constrained but

its existence is nevertheless required by the fit. In particular, we

found a lower limit of the warm absorber distance

0.02 pc, i.e. at least a factor 10 larger than that measured in the high state flux (Krongold et al. 2007).

0.02 pc, i.e. at least a factor 10 larger than that measured in the high state flux (Krongold et al. 2007).

They specifically found that the warm absorber consists of two

different ionization components which are located within 3.5 lt-days

(or 0.0029 pc) from the central massive black hole. This result allowed

the authors to exclude an origin in the dusty obscuring torus because

the expected dust sublimation radius![]() is at least one order of magnitude larger. Hence the authors suggested

a model in which the black hole accretion disk is at the origin of a

X-ray absorber wind, which forms a conical structure moving upward.

is at least one order of magnitude larger. Hence the authors suggested

a model in which the black hole accretion disk is at the origin of a

X-ray absorber wind, which forms a conical structure moving upward.

If this is the correct picture, when the continuum source is switched off, the compact warm absorber might not be observed anymore during the low state flux of NGC 4051. Our analysis showed instead the existence of a more exterior X-ray absorber, which absorbs the soft X-ray photons emitted from sources (as for example the inner surface of the conical structure proposed by Krongold et al. 2007) located (in projection) at scales larger than the torus and/or the narrow-line regions. Remarkably, this could indicate the existence of a diffuse warm material filling the wind-generated cone.

Figure 8 gives a

qualitative representation of the model.

During the high state flux (left panel) a two ionization component warm

absorber (here labeled as II) lying within a few l-days (![]() 0.003 pc) from the accreting black hole was identified by Krongold et al. (2007). Ogle et al. (2004) found that the NGC 4051 X-ray narrow-line regions can be placed at a distance of r>0.02 pc, while the optical narrow-line regions are on the scale of tenth of parsec (Christopoulou et al. 1997).

During the low state flux (right panel), the interior warm absorber

might not be observed anymore since the central engine is switched off.

A more exterior warm absorber (labeled as I) could now absorb the

X-ray photons emitted from sources located on the scale larger than the

torus and/or the narrow-line regions.

0.003 pc) from the accreting black hole was identified by Krongold et al. (2007). Ogle et al. (2004) found that the NGC 4051 X-ray narrow-line regions can be placed at a distance of r>0.02 pc, while the optical narrow-line regions are on the scale of tenth of parsec (Christopoulou et al. 1997).

During the low state flux (right panel), the interior warm absorber

might not be observed anymore since the central engine is switched off.

A more exterior warm absorber (labeled as I) could now absorb the

X-ray photons emitted from sources located on the scale larger than the

torus and/or the narrow-line regions.

This paper is based on observations from XMM-Newton, an ESA science mission with instruments and contributions directly funded by ESA Member States and NASA. We are grateful to the anonymous referee for the suggestions that improved the paper a lot. A.A.N. is grateful to R. Porter for help with the Cloudy code, to C. Gordon for solving a few issues with the XSPEC package and to Yair Krongold for many fruitful conversations while writing this paper. Our acknowledgements also to Marco Castelli for drawing the cartoon in Fig. 8.

References

- Armentrout, B. K., Kraemer, S. B., & Turner, T. J. 2007, ApJ, 665, 237 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, K., Dorman, B., & Gordon, C. 2007, ApJ, An X-ray Spectral Fitting Package - User's Guide for version 12.4.0, Heasarc Astrophysics Science Division [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S., Guainazzi, M., & Chiaberge, M. 2006, A&A 448, 499 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S., Chiaberge M., Evans, A. D., et al. 2010, MNRAS, in press [Google Scholar]

- Blustin, A. J., Page, M. J., Fuerst, S. V., et al. 2005, A&A, 431, 111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cash, W. 1979, ApJ, 228, 939 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge, M. J., Brandt, W. N., Kaspi, S., et al. 2001, ApJ, 557, 2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou, P. E., Holloway, A. J., Steffen, W., et al. 1997, ApJ, MNRAS, 284, 385 [Google Scholar]

- Dere, K. P. 2001, ApJSS, 134, 331 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, J. M., & Lockman, F. J. 1990, ARA&A, 28, 215 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Elvis, M. 2000, BAAS, 32, 1195 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland, G. J., Korista, K. T., Verner, D. A., et al. 1998, PASP, 110, 761 [Google Scholar]

- Ferland, G. J. 2008, Hazy 1, A brief Introduction To Cloudy, Introduction And Commands, available at http://www.nublado.org [Google Scholar]

- Guainazzi, M., & Bianchi, S. 2007, MNRAS, 374, 1290 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guainazzi, M., Nicastro, F., Fiore, F., et al. 1998, MNRAS, 301, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Guainazzi, M., Risaliti, G., Nucita, A. A., et al. 2009, A&A, 505, 589 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkhabwala, A., Sako, M., Behar, E., et al. 2002, ApJ, 575, 732 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krongold, Y., Nicastro, F., Elvis, M., et al. 2007, ApJ, 659, 1022 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Korista, K., Baldwin, J., Ferland, G., & Verner, D. 1997a, ApJS, 108, 401 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Korista, K., Ferland, G., & Baldwin, J. 1997b, ApJ, 487, 555 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lamer, G., McHardy, I. M., Uttley, P., & Jahoda, K. 2003, MNRAS, 338, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A., Watson, M. G., Pounds, K. A., & Elvis, M. 1987, Nature, 325, 694 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liedahl, D. A. 1999, in X-Ray Spectroscopy in Astrophysics, Lectures held at the Astrophysics School X, ed. J. van Paradijs & J. A. M. Bleeker, 520, 189 [Google Scholar]

- Longinotti, A. L., Sim, S. A., Nandra, K., & Cappi, M. M. 2007, MNRAS, 374, 237 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Longinotti, A. L., Nucita, A. A., Santos, Lleo M., & Guainazzi, M. 2008, A&A, 484, L311 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Longinotti, A. L., Costantini, E, Petrucci, P. O., et al. 2010, A&A, 510, 92 [Google Scholar]

- McHardy, I. M., Papadakis, I. E., Uttley, P., et al. 2004, MNRAS, 348, 783 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle, P. M., Mason, K. O., Page, M. J., et al. 2004, ApJ, 606, 151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti, G., Miniutti, G., Cappi, M., et al. 2006, MNRAS, 368, 903 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porquet, D., & Dubau, J. 2000, A&AS, 143, 495 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, R. L., Ferland, G. J., Kraemer, S. B., et al. 2006, PASP, 118, 920 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, R., & Ferland, G. 2007, ApJ, 664, 586 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pounds, K. A., Reeves, J. N., king, A. R. & Page, K. L. 2004, MNRAS, 350, 10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T., & Flannery, B. P. 1999, Numerical Recipes in Fortran 77, The art of Scientific Computing, 2nd edn. (Cambridge University press) [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C. S., Fabian, A. C., Nandra, K., et al. 1995, MNRAS, 277, 901 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Sako, M., Kahn, S. M., Paerels, F., & Liedahl, D. A. 2000a, ApJ, 542, 684 [Google Scholar]

- Sako, M., Kahn, S. M., Paerels, F., & Liedahl, D. A. 2000b, ApJ, 543, L115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sambruna, R. M., Netzer, H., Kaspi, S., et al. 2001, ApJ, 546, 13 [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, H. R., Donley, J. L., Antonucci, R. R. J., et al. 2003, ApJ, 597, 768 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbrugge, K. C., Fenovcik, M., Kaastra, J. S., et al. 2009, A&A, 496, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter, C. B., Tucker, W. H., & Salpeter, E. E. 1969, ApJ, 156, 943 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, P., McHardy, I. M., Papadakis, I. E., et al. 1999, Nucl. Phys. B, 69, 490 [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, P., Fruscione, A., McHardy, I., & Lamer, G. 2003, ApJ, 595, 656 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- XMM-Newton Users Handbook 2009, ed. Ness J.-U., et al. [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ...Q

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The default energy range used by the Cloudy code to

evaluate the number of ionizing photons Q is

1 Ryd-

Ryd, (Ferland et al. 1998).

Ryd, (Ferland et al. 1998).

- ... absorption

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- As noted by Sako

et al. (2000 b) and Kinkhabwala

et al. (2002), the resonance line of the O VII

triplet could be also enhanced by photoexcitation. Note however that

this would also result in a boost of all the higher order resonance

transitions of the H-like and He-like ions (Ly-

,

Ly-

,

Ly- ,

He-

,

He- and He-

and He- ),

but this enhancement is not currently observed.

),

but this enhancement is not currently observed.

- ... radius

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The torus inner edge has to be at a distance larger than

the dust sublimation radius

.

In the particular case of NGC 4051, Krongold

et al. (2007) found

.

In the particular case of NGC 4051, Krongold

et al. (2007) found  pc.

pc.

All Tables

Table 1: Best-fit parameters for the transitions identified in the soft X-ray spectrum of NGC 4051.

Table 2: The same as in Table 1 but for the identified RRCs.

Table 3:

Intensities of the observed lines and of those simulated by Cloudy corresponding to the best-fit and normalized to the O VIII Ly-![]() flux (see text and Fig. 6 for more details).

flux (see text and Fig. 6 for more details).

Table 4: Best-fit parameters for the three components of the adopted Cloudy model used to fit the RGS data.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=13cm,clip]{13673f1.ps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg22.png)

|

Figure 1: Fluxed RGS spectrum of

NGC 4051 (low state). The first order spectra of the two RGS cameras

were combined and the resulting spectrum smoothed with a triangular

kernel. The identified lines are labeled with the corresponding ion

transition name and vertical dashed lines (the big dips at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg94.png)

|

Figure 2: Distribution of residual velocity for all lines in Table 1 with respect to the cosmological one. Note that the observed shifts are consistent with the cosmological ones, i.e. no outflow or inflow is observed. The solid line represents the Gaussian best-fit to the data. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 3: Zoom around the O VII triplet lines in the low flux state. The emission lines correspond to the f, i and r components, respectively. Only an upper limit to the resonance line r can be obtained (see text). The solid line represents the best-fit obtained with a power law + Gaussian lines model (details in text). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13673f4.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg127.png)

|

Figure 4: SED used in the paper (solid line). For comparison we also give (dashed line) the SED given in Ogle et al. (2004). This was taken from the NED database and is likely to contain contamination from the hosting galaxy. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13673f5.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg148.png)

|

Figure 5: Comparison of a model with two emission components (solid line) with the observed RGS spectrum (zoom around the O VII triplet). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13673f6.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg149.png)

|

Figure 6:

Intensities of the observed (filled squares) and simulated (triangles)

lines corresponding to the best-fit and normalized to the O VIII Ly- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f7a.eps}...

...dth=6cm,angle=-90,clip]{13673f7f.ps} }\vspace*{-2mm}

\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg161.png)

|

Figure 7: The 5-35 Å RGS 1 (red data points) and RGS 2 (black data points) spectra are shown together with the best-fit Cloudy model described in the text and corresponding to the physical parameters reported in Table 4. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f8...

...}

\subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13673f8b.eps} }}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13673-09/Timg184.png)

|

Figure 8: The cartoon shows qualitatively the location of the X-ray emitting and absorbing material (see text for details). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.